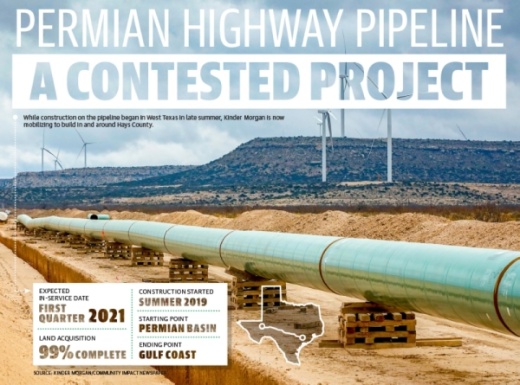

After more than a year of community meetings, negotiations, resolutions and legal action, the pipeline company Kinder Morgan is getting ready to begin construction on the Permian Highway Pipeline in Central Texas—at least if legal challenges do not stop it.

Work has already begun on the westernmost section of the 430-mile, $2 billion natural gas conduit, which stretches from the Permian Basin to the Gulf Coast, nearly bisecting Hays County. But in the Central Texas area, the company is waiting for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to issue required permits.It is what happens with those permits that will most likely determine how soon Kinder Morgan can break ground.

The endangered species question

The permit issue is at the heart of two letters of intent to sue—required before filing a lawsuit against a federal agency—filed in the last six months to try to force Kinder Morgan to perform a full and public environmental review.

The first letter, filed with the U.S. District Court on July 17, focused on the impacts of the pipeline on the golden-cheeked warbler; the second, filed Oct. 16, focuses on aquifer-based species such as salamanders.

Hays County and the Travis Audubon Society signed onto the July letter, while plaintiffs in the second included Austin, San Marcos and Kyle, in addition to Hays County.

Both letters charge that the Permian Highway Pipeline passes through endangered species habitat and that the company is trying to avoid rigorous environmental review by seeking a general nationwide permit from the Corps, which would not require it.

The members of the Texas Real Estate Advocacy and Defense Coalition funded both letters of intent, and there is a high likelihood that the organization will sue if the project were allowed to move forward with the less limited permit, according to attorney David Braun, legal council for the TREAD Coalition.

“If those permits are issued without the environmental studies that we think should have been required, I think it’s almost a certainty that TREAD will try to file a lawsuit,” Braun said.

If a lawsuit is filed, it will include a request for an injunction, which would at least temporarily keep the company from building if it is granted.

The lawsuit, however, could go forward even if the injunction is not granted—and it may not be. The legal standard for granting an injunction, Braun said, is that a judge must decide both that the plaintiff will likely succeed in court and that not granting the injunction would incur irreparable harm.

“We feel good on both those points,” Braun said. But he added, “The injunction is a very high hurdle.”

The new lawsuit

There is also an entirely new legal action on the horizon.

The TREAD Coalition is putting together a lawsuit that will challenge one of the foundations of the rules that have governed the Permian Highway Pipeline so far.

The suit will include evidence that some of the gas from the sprawling Permian Basin that will be transported by the new pipeline comes from New Mexico.

“There’s a very strong argument—it’s taken a long time to get the evidence—but there’s a very strong argument that this pipeline is not a Texas-only pipeline, but an interstate pipeline,” Braun said.

Under construction as an intrastate pipeline, the Permian Highway project is subject to only state law, but the lawsuit will argue that as an interstate pipeline is should be regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and federal requirements on environmental study, eminent domain and transparency are far stricter than those of the state of Texas.

“If we were to win that, [Kinder Morgan] would need to go and get the FERC permit before they could go forward,” Braun said. “All the condemnation they did would have not been legal.”

Shovel-ready in Central Texas

No date has been announced for when the federal permits will be issued, but Kinder Morgan expects it fairly soon. Allen Fore, vice president for public affairs, said the company expects construction activity to begin in the area in the first quarter of 2020.

He added that the company is “mobilizing” in the Central Texas area to be ready to start work as soon as the permits are issued.

“Everything is ready to go,” Fore said. “Once we get the authorization [from the Corp] to move forward, we’re prepared to go.”

The Permian Highway Pipeline has already been subject to at least one delay. In October, Kinder Morgan announced that the in-service date had been pushed back from the last quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021. Fore attributed the postponement to the wait for permits.

“This project has received a lot of attention—a lot of interest,” Fore said. “And the Corps—not only on this project but on a lot of projects—has a very high-profile role.”

The appeal

In Texas, oil and gas pipeline companies have a great deal of power to use the authority of eminent domain, according to a number of land-use attorneys. At the same time, very little in the way of public process is required, which is the subject of a separate lawsuit that charges that the Texas Railroad Commission provides so little oversight that it violates the state constitution.

That lawsuit was dismissed by a judge in June, but the plaintiffs—which include Hays County and the city of Kyle—are filing an appeal with briefs due to the court in January.

“I’m still extremely optimistic about that suit,” Braun said. ”The trial court did not agree with our position, but I think the law supports us, and I think the Third Court of Appeals has had a very good history on property rights.”

The ultimate goal of that lawsuit is a systemic change to the pipeline routing process in Texas, but Braun said that if the plaintiffs were to win the suit, it would still affect the Permian Highway Pipeline.

“If we succeed in our appeal, the process by which [Kinder Morgan] got their permit would be unconstitutional,” Braun said. “They would have to take it out of the ground.”

According to Fore, land acquisition for the Permian Highway Pipeline—upwards of 1,000 parcels over hundreds of miles—is 99% complete, which means that even as legal challenges remain, the majority of landowners on the route have sold to Kinder Morgan.

Jessica Karlsruher, who became the executive director of the TREAD Coalition in November, said that many landowners in the area she has spoken to are somewhat discouraged but are still involved in the action around the Permian Highway Pipeline.

“Some landowners definitely feel somewhat defeated,” she said. “However they are still very much engaged because they know that traditionally when pipeline are routed, additional pipelines follow the same route. So if there’s one, there will be more.”