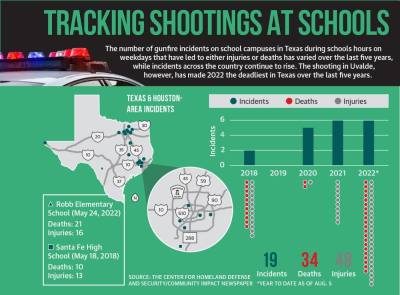

On May 24, 19 students and two teachers were killed—along with 17 others who were wounded—at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, marking the third-deadliest school shooting in the United States and the deadliest in Texas over the last ve years, according to Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit group that hosts a platform focusing on gun violence statistics across the country.

A July 17 report from the Texas House Investigative Committee, which Gov. Greg Abbott tasked with investigating the law enforcement response to the shooting, condemned the “shortcomings and failures of the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District and of various agencies and officers of law enforcement.”

The report found responders failed to adhere to their active shooter training and failed to prioritize saving the lives of victims over their own safety. FBISD officials said they believe the response in Uvalde would not happen in FBISD should a similar situation occur.

“Since Uvalde is on everyone’s mind, we’ve all heard about significant delays about people trying to engage the shooter. That’s not the way our folks are trained,” FBISD Deputy Superintendent Steve Bassett said. “Our folks are trained to engage.”

FBISD announced July 25 it is planning for a $1.1 billion bond proposal to be on the Nov. 8 ballot with $5.6 million of that allocated to address safety and security. As FBISD assesses its policies and procedures, the state is doing the same with school safety funding.

In late June, Texas leaders announced more than $100 million for increased school safety and mental health programs. Officials also called for two special legislative committees to investigate school safety and mass violence to make recommendations before the 2023 Texas Legislative session set to begin in January.

While education policy and advocacy groups hope for a more robust response from the state to prevent future violence, they said addressing school safety is not only a state issue, said Kevin Brown, executive director of the Texas Association of School Administrators, a professional association for Texas school administrators that provides networking and professional learning opportunities as well as legislative advocacy.

“It has to be a multifaceted, comprehensive approach to how we engage with our communities, engage with our schools and work with our students,” Brown said.

Response to tragedy

Since 2018, Texas has had 19 incidents in which a gun was fired on a K-12 campus, according to the national K-12 shooting database maintained by The Center for Homeland Defense and Security, a school focused on homeland security education, research and professional discipline to enhance U.S. national security and safety. Those 19 incidents led to 34 deaths and 48 wounded.

The numbers only focus on incidents that occurred on school grounds during the school day. Shooting incidents that occurred outside of school hours or during a sporting event are not included in the count.

Incidents such as these contribute to why FBISD maintains both an emergency operations plan and a safety and security master plan, Bassett said. While the emergency plan addresses how the district mitigates, prepares, responds and recovers from humanmade and natural hazards, the master plan, created in 2014, provides a safety and security road map, per FBISD’s website.

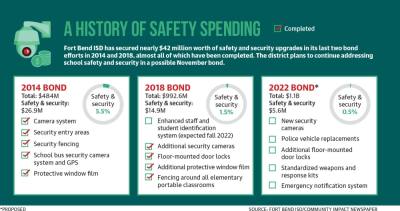

That master plan shaped the 2014 $484 million bond effort approved by voters. About $26.9 million, or 5.6%, was dedicated to safety and security and funded nearly 400 security in campuses across the district. Other bond items added security entry areas, more cameras and GPS devices for buses. All safety items in that bond were completed.

In 2018, following the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, which left 17 dead, and the Santa Fe High School shooting, which left 10 dead, FBISD convened a safety advisory committee with students, staff, parents, security experts and community members. The committee recommended additional security measures to add to the master plan, said Jason Burdine, a former FBISD board of trustees vice president and former board member for the Texas School Safety Center, a research center at Texas State University that provides school safety research and training to school districts.

“The most critical part about starting a safety and security mindset for the district is gathering your community together and having a conversation about what safety looks like for that community,” Burdine said. “For all communities and all districts, school safety means different things—and people have different expectations.”

FBISD voters approved another bond worth $992.6 million in November 2018—$14.9 million, or 1.5%, of which was for safety and security. The district installed more than 7,300 floor-mounted door locks in classrooms, fencing around all elementary portable classrooms, more security cameras, and an improved identification system expected to be complete by fall, said Bart Rosebure, FBISD emergency management coordinator.

Another bond is also expected this November, Bassett said. If passed by voters, it would include new security cameras, police vehicles, more floor-mounted door locks, and weapons and response kits for FBISD police.

Even with a portion of the anticipated bond geared toward safety and security, FBISD parents such as Susan Tosounian, a parent of one middle schooler and high schooler, still have concerns.

“I don’t think safety was as major a concern at the elementary school level because school officers and monitoring ... [has] been more prevalent in the middle school and high school level,” Tosounian said.

State solutions

Finding solutions for greater school safety and security has gone beyond just the local districts, however, as Texas grapples with how best to prevent future violence.

Luis Figueroa, policy director of Every Texan, an Austin-based non partisan nonprofit policy institute that analyzes the state’s social services safety net, said Abbott did not do enough. He said the decision on June 1 for two special legislative committees to investigate school safety and mass violence following the shooting in Uvalde was the “bare minimum” the state could have done.

“I think that the massacre in Uvalde, the massacre in El Paso and the one in Santa Fe would have justified a special session on this issue,” Figueroa said. “Because now, essentially, schools are going to be starting in the fall without any significant changes to the system.”

This comes as the Texas Education Agency told districts June 30 of safety audit requirements to be completed before the 2022-23 school year.

While the two state committees work on recommendations addressing school safety, mental health, social media, police training and firearm safety, Brown said funding is a priority for preventing future campus violence.

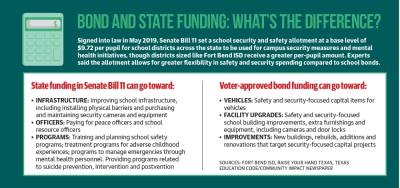

Signed into law in May 2019, Senate Bill 11 set aside a base school security and safety allotment of $9.72 per pupil for school districts across Texas to be used for campus security measures and mental health initiatives. Brown said the allotment allows for greater flexibility in district safety and security spending compared to school bonds—but it is not enough.

“We would like to see something around $150 per student or more,” he said. “Especially because that [funding] comes with some flexibility at the local level.”

Still, despite moving in a positive direction for school safety, gun regulation remains the key priority to preventing future mass campus shootings, Figueroa said.

“You might be able to harden a school; you might be able to address the important needs of mental health, but regulating guns is something we could do tomorrow,” he said. “We could put some regulations and some background checks and other restrictions like red-flag laws on guns that could go into effect pretty quickly. That would reduce the odds of another massacre at a more effective rate.”