According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 10.9% of residents in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land metro area reported being food scarce at the start of the pandemic between April 23-May 5, 2020. Between Oct. 28-Nov. 9, 2020, local food scarcity peaked at 21.4% and has since fluctuated, dropping to 14.2% between June 1 through June 13.

“With inflation, with the gas prices, we’re seeing a rising increase in the number of families who come out to us,” said Shayne Baker, a food pantry coordinator at Catholic Charities, which works with the Houston Food Bank. “Prior to the pandemic, we really saw mostly families from the Richmond and Rosenberg area, but ... as the need grew, we have really seen a lot more people traveling from farther out ... from basically the entire Fort Bend County area.”

The Houston metro’s unemployment rate dropped from 13.3% in April 2020 to 4.3% in May 2022, according to Texas Workforce Commission data. However, local food bank leaders said ongoing supply chain challenges and inflation have continued to drive the demand for food assistance while making it harder to meet those needs.

Pre-existing conditions

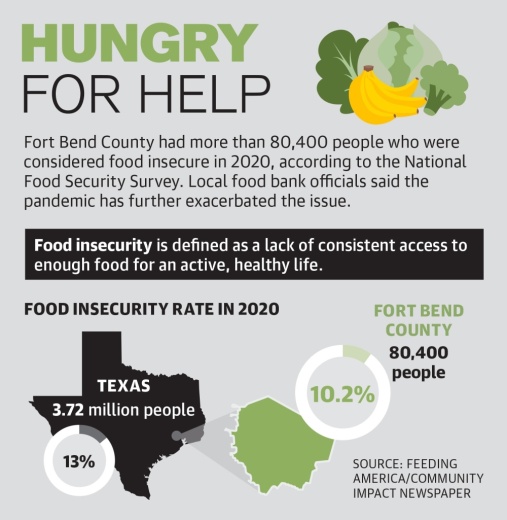

Food insecurity has long been a challenge in Fort Bend County even prior to the pandemic, local leaders said. However, a partnership between the county and the Houston Food Bank has helped assess the local need, said Shweta Arora, the county’s health communications specialist, via email.

“[Fort Bend County Health and Human Services] has partnered with the Houston Food Bank through collaborations with our community partners over the years,” she said. “We will continue to partner with the Food Bank through various outreach activities.”

While details of the collaboration with the social services division are being finalized, the relationship between the Houston Food Bank and Fort Bend County is long standing—with FBCHHS bringing a history of serving vulnerable populations in Fort Bend County.

FBCHHS can provide food assistance, emergency shelter and any temporary relief people need until a long-term solution is identified, Arora said. Additionally, the county can help connect residents to food distributions.

“FBCHHS provides an array of services, either directly or through collaborative efforts with partnering organizations,” Arora said via email. “We take into consideration the entire impact of food insecurity when working with residents to help set them up with the consistent resources they need until they can transition to being self-supported again.”

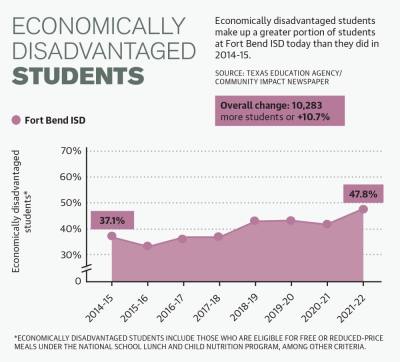

Meanwhile, between the 2014-15 and 2021-22 school years, the portion of Fort Bend ISD students who were considered economically disadvantaged—which includes students who are eligible for free or reduced-price meals—increased from 37.1% to 47.8%, per Texas Education Agency data.

Schools are often the front lines for food-insecure children, said Mia Medina, program manager at No Kid Hungry Texas, a national campaign aimed at ending childhood hunger.

“During the school year, kids can rely on school meal programs like breakfast, lunch and after-school meals, but when school is out, many of those meals disappear,” Medina said. “Summer is the hungriest time for a lot of our Texas kids and teens. That means they miss out on a lot of the consistent nutrition that they’re used to or that their families have to stretch their budgets even further than they anticipated.”

Since the pandemic began, Brian Greene, president and CEO of the Houston Food Bank, said those needs have been exacerbated as local food pantries were inundated with thousands of new clients almost overnight.

“As soon as those closures and layoffs hit, the lines went crazy long—longer than we’ve ever seen, like even after Hurricane Harvey,” Greene said.

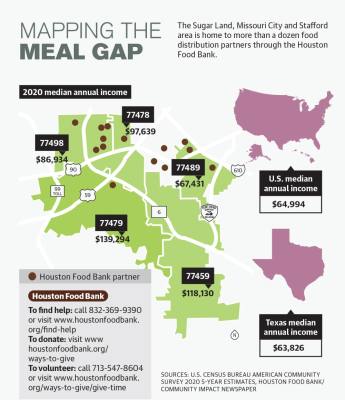

The Sugar Land, Missouri City and Stafford area is home to more than a dozen food distribution partners through the Houston Food Bank—all of which had to quickly pivot to meet the greater demand while enforcing social distancing with fewer volunteers.

The Houston Food Bank locations operating in Fort Bend County began hosting mobile food distributions and delivering food to meet the increased need. Additionally, contactless drive-thru distribution became commonplace, which Greene said had unexpected benefits.

“A lot of those working households did not feel comfortable going to their local church pantry because they would see their neighbors and they’d feel like they were being judged,” Greene said. “With curbside distribution, ... you drive through, pop your trunk and leave. ... So we were actually serving households that weren’t coming to us before.”

Although unemployment claims have since declined, local food bank leaders said demand for assistance remains high. Baker said Catholic Charities distributes 180,000 to 200,000 pounds of food per month to Fort Bend County residents.

Ongoing challenges

Even under normal circumstances, Greene said local food banks are hard pressed to meet the demand.

“Normally, we don’t meet need even on our best day because the reality of food insecurity is that food insecurity isn’t really about food; food insecurity is about income,” Greene said.

According to the Labor Law Center, Texas is one of 20 states that have not raised its minimum wage in the past decade and are still at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. Meanwhile, the consumer price index for all urban consumers has risen by 9.1% in the past year as of June, per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“It’s overall inflation that matters, not just food inflation. ... Food just happens to be their most flexible expense,” Greene said. “You can’t pay 90% of your rent. You can pay 90% of your food costs, [but] you’ll either just go hungry or, what usually happens is, make nutritional compromises.”

At the same time, the food banks, which pick up and deliver products for distribution via diesel trucks, are dealing with rising gas prices.

“We run over 60 trucks a day. We spend $3,000 plus on fuel per day, six days a week—and that was before the gas prices went up,” Greene said.

Arora said the county sees residents struggling for basic needs regularly.

“It’s difficult for someone to ask for help, and food insecurity is a domino effect that impacts every aspect of one’s life,” Arora said. “With increasing costs for basic necessities, some residents are being forced into situations where they must choose between food, housing, utilities, medications or other basic needs.”

Despite the challenges, local food bank leaders agreed the biggest hurdle is restoring the backbone of their operations: the volunteers. Greene said the Houston Food Bank had about 85,000 volunteers per year prepandemic and is now at about 50,000.

“The whole volunteer pool just got decimated in the pandemic,” Greene said. “Bringing those volunteers back so we can say more yeses to the difficult donations is a big way that we’re trying to adjust.”

Regardless of the challenges, Arora said the problem falls on the county.

“It is the responsibility of the county to provide for the basic needs of the most vulnerable residents when they cannot provide for themselves,” Arora said.