That requirement is still in place two years later, but health care advocates in Texas and Houston said they are worried about what could happen when it ends and millions of people have their safety nets put into jeopardy. The Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, estimated as many as 1.3 million Texans could be deemed ineligible for Medicaid once the public health emergency ends. Roughly 3.7 million of the 5.2 million Texans enrolled in Medicaid will have their eligibility redetermined once the emergency ends, according to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. About 75.9% of Texas Medicaid enrollees are children, according to the HHSC.

According to census data released in March, Texas has a disproportionate rate of uninsured individuals com•pared to the national average. In 2020, the national uninsured rate fell to 8.7% from 15% in 2013. According to U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey results, Texas’ uninsured rate was double the national average at 17.3%•.

Carol Paret, Memorial Hermann’s senior vice president and chief community health officer, said ending the extension would increase Texas’ number of uninsured individuals. Memorial Hermann opened its Sugar Land hospital in 2006.

“Texas already has one of the highest numbers of uninsured in the country,” she said. “When you have so many people in your community that don’t have access to care, it impacts •health overall.”••The pandemic also shined a light on a debate that has been ongoing since 2010: whether Texas should expand Medicaid coverage. That debate will come up again when the state Legislature meets in January. Some local lawmakers said they support reform for better health care access—but think expansion is unsustainable.

"When Medicaid has been expanded in other states, the cost burden has been so great it hasn’t been sustainable or beneficial to their health care program,” Republican state Rep. Jacey Jetton said. “Last session, we worked on legislation to continue to provide better access to affordable health care through open market concepts in areas of telehealth medicine, expanded broadband and increased flexibility to who can administer vaccines. We will continue to push for reforms for better health care access and affordability for all Texans.”

State of Medicaid

The public health emergency was still in place as of May with an expiration date of July 15. However, the government also requires a 60-day notice before Congress can allow the emergency to expire. That notice was not given May 15, meaning the emergency is likely to be extended into October, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research institute that analyzes federal and state budget policies.

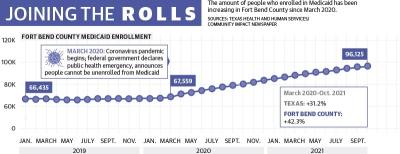

Since the emergency was declared, Medicaid enrollment has increased to its highest mark ever in Texas, hitting 5•.2 million as of February, up from 4.2 million in March 2020, according to the HHSC. ••The number of people enrolled hovered around 66,000 for Fort Bend County prior to the pandemic in 2019. Since then, Fort Bend County enrollment grew to more than 96,000 as of the most recent confirmed data from October 2021. HHSC’s preliminary data from February estimates around 100,813 Fort Bend County residents are now enrolled in Medicaid.

When the public health emergency ends, a portion of Medicaid enrollees will have their coverage automatically renewed if they are deemed eligible. There will also be an unwinding period of up to 12 months during which states will work with individuals who were not automatically re-enrolled to help them keep their coverage if they are still eligible, though Texas plans to only use six of those months, HHSC officials said.

For states to be successful, they will have to focus on two key areas, said Farah Erzouki, senior policy analyst with the CBPP: streamlining the application renewal process and communicating effectively with enrollees.

The CBPP recommends states increase capacity for renewals that are determined using electronic data matches, which will help avoid having to rely on enrollees to complete a renewal form or submit documentation, Erzouki said.

Additionally, Erzouki said it will be crucial for states to allow enrollees to renew their policies through a variety of methods, including online, by phone, by fax, by mail and in person. Texas is among the 33 states to allow renewals by all five methods, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

A looming crisis

There is no estimation from the HHSC at this time for how many people could be determined ineligible and unenrolled as part of that process, HHSC Press Officer Kelli Weldon said. Officials will get a better idea of that number after they conduct a full analysis during the unwinding period, •she said.••In an emailed statement, Jacquelyn Minter, Fort Bend County’s health and human services director, recommended Medicaid enrollees update their information on www.yourtexasbenefits.com and return requests for information as soon as possible.

Children are most at risk of being unenrolled when the public health emergency ends, said Laura Dague, associate professor with the Texas A&M University Public Service and Administration Department who specializes in the economics of public health insurance.

“The vast majority—and that means, of course, the people who kind of stayed on [Medicaid] longer than expected—are low-income kids. I think we will see the most disenrollment in that group,” Dague said.

Paret said unenrollment can have a domino effect on students’ health and school attendance, exacerbating the health care gap for future generations.

“Our belief is the No. 1 way that you improve health is [breaking] the poverty cycle,” she said. “You can break the poverty cycle through education—but kids can’t be educated unless they’re healthy and in school.”

Debate over expansion

Certain population groups are required to be covered by Medicaid under federal law, including people who are below a certain income level and are also pregnant, are children, have a disability or are over age 65.

The health care policy is jointly funded by states and the federal government with the federal government paying 90% of the cost of health care for those insured by Medicaid and states paying 10%, according to the KFF.

When the federal government signed the Affordable Care Act into law in 2010, each U.S. state was given the option to expand Medicaid coverage to nearly all adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, an annual income of $17,774 for an individual in 2021, according to the KFF.

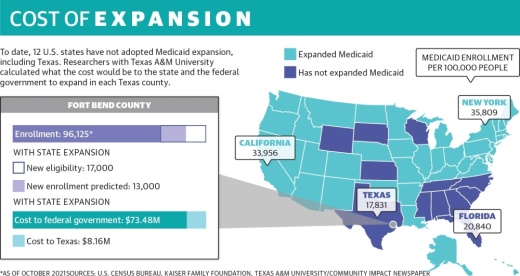

Texas is among 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid. Of those 12 states, Texas also has set the highest bar for people to qualify based on income, only allowing people to enroll if they make less than $103 per month.

“Fort Bend County has a lower proportion of uninsured residents than many other counties in Texas; however, there are some areas across our community where health care insurance coverage is at a much lower rate,” Minter said in an email. “The expansion of Medicaid would likely result in part of this uninsured population becoming eligible for federal health care programs.”

Researchers with Texas A&M University released a study into the economic effects of Medicaid expansion in 2019.

The study found expanding Medicaid would make about 17,000 more people eligible in Fort Bend County and result in about 13,000 new enrollments. This would come at a cost of around $73.5 million to the federal government and $8.2 million to Texas.

Ahead of the next legislative session in January, several local representatives said Medicaid is top of mind. Those opposed to expansion said Texas would still be on the hook for about $500 million in program costs and questioned the effects it would have on improving health care outcomes in the state. But Paret said the cost is unavoidable.

“You pay for it one way or another,” she said. “If you deal with health issues early, they’re going to have less impact and less cost. If you wait because people don’t have access to care until they’re advanced, there’s more cost.”