“Students are still wearing black ribbons. There are more adults and police officers around, and hall sweeps are more frequent,” said Ioana Nechiti, a senior at the school. “There’s more vigilance.”

School district trustees and officials have been grappling with how to respond. On Feb. 13, trustees voted down a measure that would have allowed the district to expedite installing metal detectors at some schools, but Houston ISD school board President Sue Deigaard said the item is almost certainly going to return for further consideration.

“From what I heard, trustees want a comprehensive safety strategy for our kids that metal detectors may or may not be a part of,” Deigaard said. “It doesn’t necessarily just have to be equipment; there’s practices and procedures to think about.”’

The event marked the first shooting death inside a school in the United States in 2020, according to data tracked by the Center for Homeland Defense and Security. According to its database, 514 shootings have occurred on school grounds in the U.S. since 2010.

The event put additional attention on district leadership, which was recently cited in a state audit for inefficiencies in its security management practices and not holding state-required safety meetings.

Complex challenge

The incident at Bellaire High typifies how difficult it is for a school to deal with threats to safety, said Alan Bragg, the executive director of the Texas School Safety and Security Council, an outreach arm of the architecture firm PBK.

“We’re all searching for solutions, and that is one thing that has improved—we’re all willing to send resources, share ideas and solve whatever needs to be fixed,” said Bragg, who at one time served as a night shift lieutenant for the HISD Police Department.

Metal detectors are one way to keep weapons from getting past school doors, but there are many other considerations, Bragg said.

A report by the Texas Association of School Boards noted a single metal detector may cost around $4,000 to $5,000, but the cost to operate them “requires a significant commitment of school resources and staff time.”

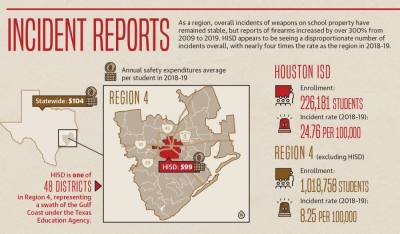

According to district reports, HISD has spent $29.3 million from the 2012 bond on security improvements and has an annual budget of $24 million for safety and security, which includes a police force of around 200 officers.

In recent discussions with community members, interim Superintendent Grenita Lathan told trustees police staffing emerged as a top concern.

“What I’ve heard is, ‘We want more police officers,’” she said. “That is another group of employees that we need to look at their pay disparities because we have a high number of police officer vacancies right now.”

The district is also going to look at how to hire more social workers either by adding positions or partnering with local agencies, Lathan told the board.

PBK’s 32 best practices for school safety include metal detectors as a viable layer of security. Other recommendations include adopting a clear backpack policy, improved video surveillance and social media monitoring.

“There are a number of practices where the investment is not huge but can be very effective at prevention,” Bragg said.

Strategy and advocacy

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for school safety, said Jeff Caldwell, the associate director of school safety readiness for the Texas School Safety Center, a clearinghouse for resources to help school districts plan for emergencies.

“That said, there are some things that work and should be emphasized, such as having a clear reporting process and threat assessment teams,” which are campus-level groups that review reports and coordinate a response, he said.

Some of these practices were reinforced with Senate Bill 11, passed in the last state legislative session and taking effect Jan. 1, 2020. The law also provided for additional funding, including $1.7 million estimated for HISD, to invest in security.

The other reality is that safety is now a year-round concern, Caldwell said. In addition to advising districts, the agency also collects security audits every three years, rolling them into a statewide report.

“What we tell schools to practice is to be doing this audit work all the time, constantly reviewing plans as well as physical security systems, but also campus climate and students’ well being,” Caldwell said.

While shootings frequently conjure debates over national and state gun control laws, Nechiti, a member of Bellaire High’s Students Demand Action group, said there are opportunities for local governments.

“Usually the focus is on the Legislature to change the laws ... but there are actions by schools, school boards and city councils, a lot of precautionary measures, that can be very effective,” she said. “But you have to recognize the issue transcends state, location and what school you go to.”

She and dozens of her fellow students at Bellaire High and other schools staged a sit-in at the HISD administration building to rally for action to protect students from firearms. She also joined Izzy Richards, also a senior at Bellaire High, and Emily Ramirez, a senior at Heights High School, in asking Houston City Council’s Public Safety Committee on Feb. 5 to consider ways that local ordinances can improve safety.

“I had been doing some advocacy before this, but I never thought it would become a real issue in my community,” Nechiti said. “It’s terrifying and shocking and horrible.”

Culture and communication

The discussion of school safety also comes as the district has been handed a comprehensive audit of its operations, including security management.

The Legislative Budget Board report, released in November, found the district’s safety management practices suffered from “inefficiency, poor communication and planning, and the omission of key safety and security responsibilities.”

The report found the district had failed to hold meetings of the state-mandated safety and security committee since 2016, and the police chief was not participating in regular cabinet-level meetings with the superintendent.

The district declined to comment on whether it had addressed these findings. However, Deigaard said that since becoming board president in January, she has not been invited to a security committee, which is required to meet three times a year under a state law adopted in 2009.

Bragg and Caldwell both said improving communication and data collection are fundamental.

“The hard part is they have to work off the data they have,” Caldwell said. “But what’s key is, the district must have a process to unify the information coming in and deal with it promptly. ... No one wants to report and then think no one did anything about it.”

More reporting can create a perception of more problems, but it also points to a better culture and raised awareness, Caldwell said.

“More reporting of incidents does not mean a school is less safe. In fact it could mean the exact opposite,” he said.

Weapons incidents at HISD have averaged 54 reports a year since 2010, according to district discipline data. Reports include firearms, knives and other weapons.

The district’s “See Something, Say Something” campaign encourages students to submit reports online and via mobile app. At Bellaire, officials said students could have reported that a gun was brought to campus earlier in the day, but they did not take that step.

“A child died on school grounds. Schools should be safe places. Kids should be free of that fear of it happening on campus,” Deigaard said.

Editor's note: A modified version of this report also published in the Heights/River Oaks/Montrose edition of Community Impact Newspaper.