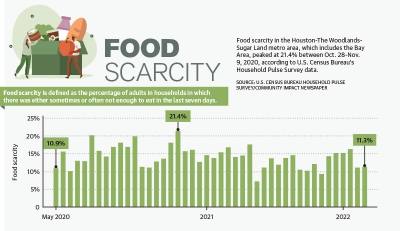

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 10.9% of residents in the Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land metro area—which includes Clear Lake, League City and beyond—reported being food scarce at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic between April 23-May 5, 2020. Between Oct. 28-Nov. 9, 2020, local food scarcity peaked at 21.4% and has since fluctuated, dropping to 11.3% between March 30-April 11, 2022.

Interfaith Caring Ministries, which provides several services, including free food to Clear Creek ISD and Friendswood ISD families in need, is still seeing high demand and increasing costs, Executive Director Suzy Domingo said.

“The clients are very grateful for everything they’re getting, but they need as much as they can get, and we’re not able to fill the entire need right now,” she said.

Increasing demand

When the pandemic began, Brian Greene, president and CEO of the Houston Food Bank, said local food pantries were inundated with thousands of new clients almost overnight.

“As soon as those closures and layoffs hit, the lines went crazy long—longer than we’ve ever seen, like, even after Hurricane Harvey,” Greene said.Donnie VanAckeren, president and CEO of the Galveston County Food Bank, said he saw a similar increase. During one early COVID-19 distribution, he called his pastor and asked him to pray there would be enough food for each family, which, miraculously, there was, he said.

Despite demand having tapered off a bit after the pandemic, it is beginning to spike again. VanAckeren has particularly seen an increase in the number of young couples relying on the food bank.

“There’s just not enough money at the end of the month, so we want to be that helping hand to them, and that’s what we do,” he said. “I just hate it that our economy’s going this way, but we’re here to help.”

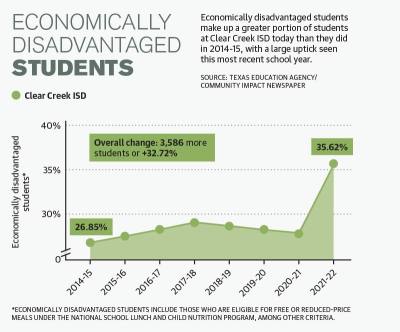

There has been a similar increase in food scarcity among CCISD students. Since at least 2011, CCISD’s percentage of economically disadvantaged students—which includes those eligible for free or reduced-price meals—has hovered around 28%.

However, during the 2021-22 school year, the number suddenly jumped to 35.62%, according to Texas Education Agency data. CCISD is offering free meals over the summer for children, Senior Communications Specialist Sydney Hunt said.

Ongoing challenges

Even under normal circumstances, Greene said local food banks are hard pressed to meet the demand.

“Normally, we don’t meet [the] need even on our best day, because the reality of food insecurity is that food insecurity isn’t really about food; food insecurity is about income,” Greene said.

According to the Labor Law Center, Texas is one of 20 states in the U.S. that has not raised its minimum wage over the past decade and is still at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. Meanwhile, the consumer price index for all urban consumers has risen by 8.3% in the past 12 months as of April, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“You can’t pay 90% of your rent. You can pay 90% of your food costs, [but] you’ll either just go hungry or, what usually happens is, make nutritional compromises,” Greene said.

Domingo sympathized with residents unable to earn enough to afford basic needs.

“There are jobs out there. They’re just not paying enough to keep up with the increase of living,” she said.

At the same time, the food banks, which deliver products for distribution via diesel trucks, are dealing with their own set of challenges as gas prices rise, Greene said.

“We run over 60 trucks a day. We spend $3,000-plus on fuel per day, six days a week—and that was before the gas prices went up,” Greene said.

In the first quarter of 2021, the Galveston County Food Bank spent about $4,800 a month on fuel to deliver food to area food banks. This year, it has been about $9,600 per month so far, VanAckeren said.

Rising food costs affect distributors as well. In April 2021, Interfaith gave about the same amount of food to residents as it did in April 2022 at a cost of $20,600. This April, the cost was $27,400, Domingo said.

To offset some of the cost to struggling nonprofits during the pandemic, the Galveston County Food Bank has stopped charging nonprofits fees for the cost of delivering food to them to distribute. Both VanAckeren and Domingo said they have seen donations dry up a bit recently. While local churches and groups, such as Boy Scouts, have been reliable food donors in the past, they have been more scarce recently, meaning Interfaith has to spend more of its own money buying food to meet demand, Domingo said.

VanAckeren has seen a similar dry spell in terms of donations.

“Gas prices, food at the grocery store—those are all expenses that are taking up those donations that we normally get,” he said.

VanAckeren and Domingo said they want residents to know they can rely on local food banks to remove the stress of finding food during these hard times.

“We are so, so blessed. Galveston County is just a wonderful place, and the people are so giving,” VanAckeren said. “But this is a tough time for everyone. My heart aches.”