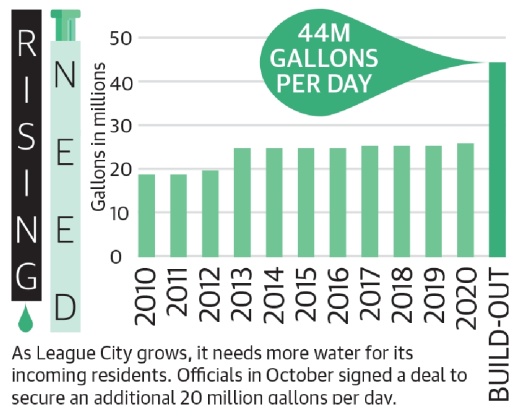

However, city officials have known for several years that 25 million daily gallons is not enough for future growth, and so they began their quest to secure more.

League City City Council in October signed an agreement with the city of Houston to reserve an additional 20 million gallons of water per day at an annual cost of $530,000 to start, but the city’s work is far from over. To acquire the reserved water, the city needs to replace the infrastructure that transports it and expand the plant that treats it—projects that will take years and have costs that will lead to water rate hikes for residents.

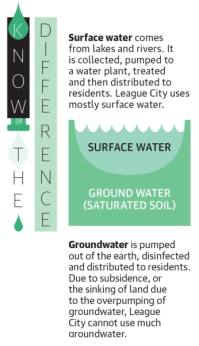

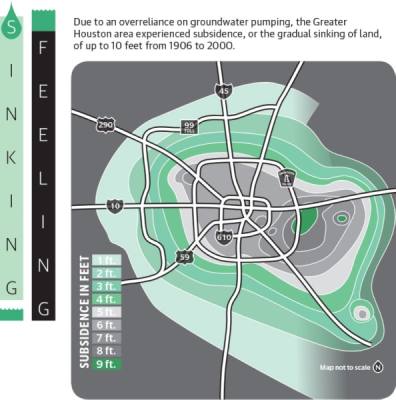

Additionally, officials have to be sure they do not overrely on groundwater in the meantime because League City is in a subsidence area that has seen land sink several feet since the early 1900s due to overpumping of groundwater, officials said.

“Water has become the new black gold, like we •thought of oil,” Mayor Pat Hallisey said. “Water is the heart of civilization.”

QUEST FOR SURFACE WATER

League City’s population of about 106,000 grows annually by a few thousand residents. Considering the city is only halfway built out, officials expect the city’s population to cap out at around 200,000 residents in the next few decades, and with residents comes a need for water.“It is the elixir of life. We can’t live without it. Growth is hinged on it,” City Manager John Baumgartner said. “It’s incumbent upon us to plan for that growth we know is coming.”

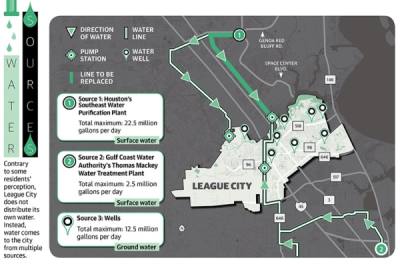

Some residents believe the city acquires and treats its own water, but that is not the case. League City gets most of its water from the Southeast Water Purification Plant near Ellington Airport in Houston. A smaller portion comes from the Thomas Mackey Water Treatment Plant in Texas City, and the city has wells from which groundwater can be pumped to supplement any shortfalls, Baumgartner said.

However, these three sources do not provide enough water for League City’s future needs. Right now, the city gets about 22.5 million gallons per day from the Houston plant and 2.5 million gallons per day from the Texas City plant. Another 12.5 million can come from groundwater wells, but the city can only extract 10% of its daily water need from wells without incurring heavy penalties, officials said.

“The city has recognized that under current contracts, they would not have enough water for their anticipated growth,” said Ivan Langford, an adviser to the Gulf Coast Water Authority who helped the city secure more water.

After doing calculations, city officials determined the city will need an additional 20 million gallons of water per day—a total of 44 million gallons daily—at build-out. The question then became where League City should acquire that water.

Baumgartner and his staff considered a few sources but decided it would be best to get the extra water from the Houston plant starting in the next few years, Public Works Director Jody Hooks said. The plant already provides most of the city’s water, all of which comes from the Trinity River and is pumped under the Houston Ship Channel to the Houston plant, officials said.

“At the end of the day, I would say it’s the only available body of water at that volume,” Hooks said.

INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDS

The water line that carries water from the Houston plant to League City is about 50 years old and nearing the end of its lifecycle. Additionally, it needs to be bigger if it is going to be transporting nearly double the amount of water it does today, Baumgartner said.“We’re buying a larger pipe for the future needs of the city,” Langford said. “You’ve got to build for the long term, or you’re spending the money twice.”

By about 2024, workers will have finished the process to replace the line with a bigger one at a cost of about $117.8 million. League City, the line’s primary user, will pay $62.6 million for the project. Other cost sharers include the cities of Houston, Friendswood, Webster and Pasadena, officials said.

Additionally, the Houston plant will need to expand to handle the treatment of an additional 20 million gallons of water every day. That project is expected to cost about $100 million total, Hooks said. The expansion is years out, but League City is already considering the cost and timeline.

“That’s not very far away,” Baumgartner said.

League City officials expect to spend about $501 million over the next 10 years on water-related projects, including the Houston deal, the line replacement, the plant upgrades and related work. One of the main ways the city intends to pay for that work is through water rate increases.

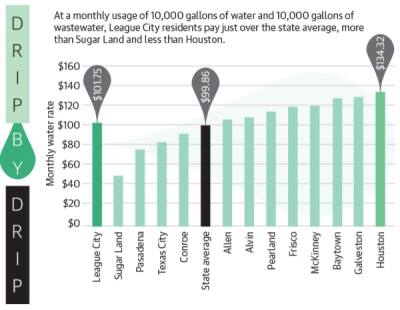

The city hired Willdan, a financial consulting business, to assess League City’s water rates and offer potential increases that could meet the city’s project needs. League City residents pay just over the state average in water and wastewater rates.

At a monthly usage of 10,000 gallons of water and 10,000 gallons of wastewater, League City residents pay $101.75, just over the state average of $99.86. League City’s rate for this volume of water is less than Houston’s at $134.32 but more than Sugar Land’s at about $50. League City’s water rates will soon increase to help pay for several water-related projects.

League City City Council will decide in the coming weeks how and when the city’s water rates will increase. Other revenue sources, such as capital recovery fees, bonds and growth, will help mitigate the costs, officials said.

“[Baumgartner] believes today’s high costs are tomorrow’s bargains,” Hallisey said. “The quicker we get to this and get it done, the better off we’ll be.”

WHY NOT GROUNDWATER?

One water-acquisition avenue League City explored was groundwater, or water that is underground, as opposed to surface water, which comes from rivers and lakes. But there is one major reason this is not viable: subsidence.The Greater Houston area has suffered from subsidence, or the gradual sinking of land, for decades. Before the 1970s, municipalities pumped water out from underground so much that the land started to sink, especially in areas closer to major bodies of water. Some parts near the Houston Ship Channel sunk up to 10 feet, even swallowing a subdivision in one case, Langford said.

League City experienced 4 to 5 feet of subsidence throughout the 20th century and as such is designated as part of Subsidence Area 1, according to the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District. Groundwater can account for up to only 10% of total water use for municipalities that fall in this area, Hooks said.

That said, officials will likely have to rely on groundwater at least a little bit in the years leading up to the expansion of the Houston plant, which could be complete as late as 2030. The city would avoid using so much groundwater as to incur fees, Hooks said.

“In between there, we do understand that we’ll probably have to use a combination of our groundwater source and surface water source to bridge that gap,” he said.

Knowing using only groundwater for build-out was off the table, League City officials instead opted for more surface water. Taking saltwater from the Galveston Bay and treating wastewater were two options, but both are more costly than treating freshwater, Baumgartner said.

With growth on the horizon, officials said they acted at the right time to acquire enough treated water for residents today and in the future.

“I think it’s the right time,” Hallisey said. “I don’t think we can put it off any longer.”