Now, on the back end of a global pandemic, local restaurants face a new crisis: workforce shortages.

The Gulf Coast Workforce Board, the public workforce system in the 13-county Houston-Galveston region, found the restaurant industry had the second-highest job demand among all industries in February. About 20,573 food industry jobs in the region, including servers, food preparation workers and various positions in fast-food chains, were unfilled at the time. The restaurant industry is struggling to stay afloat amid the high volume of customers now coming in, business owners said.

Some restaurants have begun offering incentives, such as hiring bonuses or rate increases after a probation period, to entice potential employees to apply. Even these strategies are not working, said Lauren Perez, the owner of Mobile Mixology, a business that provides bartenders for catering or events in the Bay Area.

“Before the pandemic, servers and bartenders came a dime a dozen, honestly,” Perez said. “After COVID, we were lucky if we got a handful of applicants, and we were lucky if any of them showed up to the interview. It’s been a doozy.”

Unemployment factors

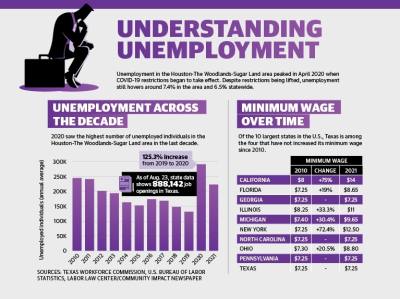

Due to a booming number of job openings, Gov. Greg Abbott announced to the U.S. Department of Labor on May 17 that Texas would be opting out of federal unemployment compensation related to the COVID-19 pandemic effective June 26, which included the expiration of a $300 weekly supplemental benefit.

In May, the number of Texas job openings almost equaled the number of Texans on unemployment, and about 60% more jobs were open at the time than there were just before the pandemic. As of early August, there were over 902,000 job openings across Texas, according to WorkInTexas.

Additionally, Abbott’s decision was also influenced by the fact that according to the governor’s office, about 18% of filed unemployment benefits were found to be fraudulent.

However, Jonathan Lewis, senior policy analyst with Every Texan, said taking away unemployment only harms those who rely on it. Every Texan specializes in strengthening public policy to give Texans equitable access to health care, education and jobs.

“I think it’s kind of a short-sighted strategy to cut off these resources when people have that money coming into their pockets,” Lewis said. “They’re then able to continue to buy the goods and services that support businesses, and so you know, it’s kind of like shooting yourself in the foot if you’re going to cut off these federal benefits while people are still trying to find employment that is suitable for them.”

Another issue with returning to the workforce for some unemployed workers is salaries not meeting the needs of workers to afford basic things, such as child care.

The average Harris County family of four needs to bring in $6,084 monthly and the average Galveston County family of four needs $6,303 monthly to afford housing, food, transportation, health care and other necessities, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit that considers the needs of low- and middle-income workers in economic policy discussions.

“Wages really benefit society as a whole, so seeing workers be able to kind of negotiate wages up is a really good thing for everybody,” Lewis said.

The state’s minimum wage has remained $7.25 for more than 10 years, while the national average has increased to $9.21, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“I think it’s really important to think about who is being impacted by these cuts, and it’s really our most vulnerable Texans,” Lewis said.

Local business reactions

Area business owners said COVID-19

has affected people’s work ethic and expected compensation, resulting in people who would rather not work than get a job.

Colton Trout owns Paradise Tropical Wines in Kemah and is also a business coach for area business owners. One local boutique owner he coaches hired a few employees in recent months and quickly fired them because they would regularly not show up for work, Trout said.

“A lot of people are having difficulty one, finding people to apply, and then two, finding people that are good quality and want to work,” he said. “Because everybody’s on unemployment, everybody’s not wanting to work in general.”

Trout said he is lucky to have the quality bartenders he employs, but he is also struggling to find adequate workers. Trout said he saw the problem coming.

“When the government is willing to give you free money, ... then ... I wouldn’t want to work,” he said.

Manish Maheshwari owns CoCo Crepes, Waffles & Coffee in League City. Over the summer, he closed Little Bella Mia, another restaurant he owns, partly due to the workforce shortage. Maheshwari said many “little guys” such as himself are suffering with some restaurant owners having to practically live at their restaurants to keep them functioning.

“It’s been a disaster,” he said.

Gina Kuper oversees human resources for her family-owned Mamacita’s Mexican Restaurant in Webster. Before COVID-19, the restaurant employed 18 to 20 servers, but 10 to 12 are working now, she said.

“People don’t have the desire to work like we used to,” she said.

The restaurant may soon limit its menu or increase prices to help offset the restaurant not having the help it needs to run efficiently, Kuper said.

Jimmy Ritz owns Angelo’s Pizza and Pasta in Webster. He said it has been difficult to find help since January, though the restaurant was able to hire several 16-year-olds over the summer.

“They are available because they do not qualify for unemployment because it is their first job,” he said in a written statement. “However, they are now going back to school, so we are likely going to have a tough time unless we can get more hires.”

Perez uses her experience to consult other bars and restaurants. She said she understands workers’ desire to be paid more but that it is not always possible for restaurants, especially coming out of a damaging pandemic.

“A lot of people tell [us] to pay more; I get that, but if we pay our staff more hourly, that means we have to account for that in the cost of food and beverages,” she said. “It’s hard to justify paying your staff more, at least right now, when these businesses don’t have the money.”

Potential solutions

Melissa Stewart, executive director of the Texas Restaurant Association, said hiring and referral bonuses are common when trying to recruit more staff. In the meantime, restaurants have taken many measures to stay afloat, including closing for a few extra days or changing hours of operation.

While some are eager to return to the workforce, the challenges of finding good child care for single parents is still weighing on families, Stewart said. Employment may resume at a normal rate this fall as schools and day cares open up to give those parents a chance to work, she said.

Perez said some of the fix could come from business owners.

Traditionally, service industry workers have been thought of as “warm bodies”; when one would quit, there would be another 10 waiting to take their place, Perez said.

Now, workers want to know what they are doing is valuable to themselves and others. They want to be praised and compensated for good work, creating a mindset that makes them less likely to leave, Perez said.

“Your employees just want to be recognized,” she said. “We’re all human, and by nature we like to be cared about.”

Mamacita’s is attempting this by offering gifts and outings to employees, Kuper said.

Meanwhile, Stewart encourages restaurateurs to highlight the benefits of working in the industry.

“We’re great for somebody who needs that extra little income,” Stewart said.

Emily Jaroszewski, Anna Lotz and Hannah Zedaker contributed to this report.