“We were at a point where we had to ramp up our takeout business. ... All of that has, in hindsight, helped us with what’s going on now,” he said.

Business dropped as the state forced dining rooms to close. Then came Dallas County’s shelter-in-place order March 23. Richardson’s order came two days later.

“We’re asking our business community to make a tremendous sacrifice, and that’s not lost on us,” Mayor Paul Voelker said during a Richardson Chamber of Commerce board meeting.

“We’ve become a more service-oriented community. Our service industry is really taking it on the nose, and their employees are really hurting.”

The survival of small businesses is essential to the nation’s ability to regain footing once this crisis is over, said Paul Nichols, executive director of the Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship at The University of Texas at Dallas.

“They can throttle up a lot quicker,” he said. “The problem, though, is that they also don’t have the resources of a juggernaut, so they tend to throttle down a lot faster, too.”

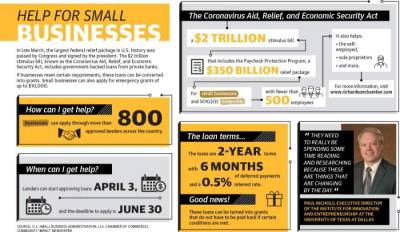

The public and private sectors have stepped in to soften the blow to the economy by providing monetary relief. But with so much out there, it is important that business owners focus on finding the relief that is right for them, Nichols said.

“They need to really be spending some time reading and researching because these are things that are changing by the day,” he said.

The strain on small businesses brought on by the coronavirus is threefold, said Marta Gomez Frey, director of the Collin Small Business Development Center.

Many establishments are not only struggling to get customers through the door but are also grappling with skeletal workforces and inventory shortages, Frey said.

“The overall mood among business owners is sadness, desperation and frustration,” she said.

In 2019, the U.S. Small Business Administration reported a total of 256,060 companies with 250 or fewer employees across Collin, Dallas, Tarrant and Denton counties. This represented roughly a 9% increase as compared to the previous year’s total.

Companies of all sizes have been forced to reinvent themselves in the wake of the crisis. Across DFW, businesses have pivoted to provide essential services.

“Good entrepreneurs are always able to take advantage of a shifting market or environment and make sure they stay just in front of customer needs,” Nichols said.

Lockwood Distilling in Richardson has halted the production of spirits and is instead using high-proof alcohol to make hand sanitizer. The business is selling the product while also donating it to organizations in need.

“We are going to do our best to share the wealth and get it to as many people as possible,” owner Evan Batt said.

Other companies have shifted to serve groups hit particularly hard by the virus. Richardson-based Orchard at the Office used to deliver fresh produce and healthy snacks to office complexes; now, it delivers those same products to the homes of people at higher risk for the disease.

“This benefits seniors, people with compromised immune systems, pregnant women ... because they are receiving products that have been minimally touched and minimally processed,” owner Amy Long said.

Adapting to this new environment can also help companies avoid furloughs or layoffs. At Asian Mint in Richardson, servers now take carryout orders or drive deliveries.

“As a business owner, I’m willing to eat all operational expenses because it’s the people I care about the most. They have mouths to feed and families as well,” owner Nikky Phinyawatana said.

“Feeding souls” has always been the mission of Asian Mint, she said, and that does not stop just because people are sheltering in place. So Phinyawatana launched a meal kit program, featuring a recipe card and fresh, premeasured ingredients.

“The goal was to get people cooking at home, building a community and having something to bond over,” she said.

Protecting the local workforce is especially crucial at a time when national unemployment claims are 32 times higher than they were this time last year, according to April 4 data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Despite this, some businesses have opted to cut their losses and close for the time being, said David Denney, president of the Greater Dallas Restaurant Association.

“Some owners have made the choice to go dark, put their people into the unemployment system and try to hold back some of their reserves for when this thing blows over,” Denney said.

In all crises, there is also opportunity, Nichols said. While inconvenient, these adaptations may prove valuable down the line.

“For good or for bad, a lot of companies are going to be shaken up by this,” he said. “The decks are going to be shifted, so what can you do to take advantage of that changing situation?”

Even as limits on businesses are lifted, it is going to take time for companies to make up for the loss in sales, to regain employees or to restock supplies, Frey said. For some, it could take months or even years.

“It’s going to take a while for all those pieces to get back in order to be whole again,” she said.