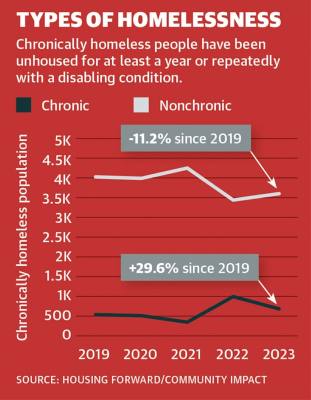

In Dallas County, about 3,692 people were counted as experiencing homelessness during a single night in January. Housing Forward, a North Texas organization serving the unhoused population, conducted the federally mandated point-in-time count, which is meant to provide a snapshot of trends regarding homelessness Jan. 26. The organization released data related to the count in April, which showed that homelessness in Dallas and Collin counties has decreased by 4% since 2022.

The decline comes as a result of targeted efforts from the city and local agencies, but housing advocates said more needs to be done to provide housing to all Dallas residents. Advocates and city officials cited a lack of affordable housing, widespread misinformation, stigma and misplaced efforts as some reasons for why homelessness is still high despite the decline.

Joli Angel Robinson, president and CEO of Housing Forward, said the most accurate count of people experiencing homelessness is “a hard number to capture” because many unhoused people couch surf with relatives, shelter in cheap motels or even live out of their car. Those people are still considered homeless from a federal standpoint.

“There’s a lot of people experiencing homelessness that probably even live in Lake Highlands [and Lakewood] that are doubled up [in relatives’ homes] and are a little more invisible,” Robinson said.

Demographics

Derek Hayes, a Black man experiencing homelessness, said he often spends $15 on a bed at the homeless shelter Dallas Life, but when he has a little extra money, he books a cheap motel room. He said he has experienced homelessness for extended periods of time since 2009 when his caretaker died of cancer.

“[I’ve had homelessness] breaks from time to time; I have had my own place before,” Hayes said. “But I have lived in [homelessness] for such a long time, and I’m still living in it. ... I know how it is to have been blessed with something and finding out the next day that you might lose it.”

The population of people experiencing chronic homelessness, like Hayes, decreased 32% in Dallas and Collin counties from 2022 to 2023, according to Housing Forward data. People who are chronically homeless have experienced homelessness for at least a year, or repeatedly, while struggling with a disabling condition such as a mental illness, substance abuse or physical disability, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

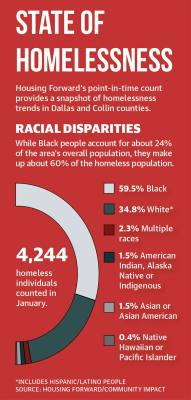

Robinson said there are notable racial disparities in the unhoused population. While accounting for only about 24% of Dallas County’s overall population, Black people, particularly men, make up about 60% of the unhoused population, according to Housing Forward data.

“We know that Black men are disproportionately represented in our unhoused population because of a lot of other systems that may have failed and negatively impacted Black men,” Robinson said. “It’s unfortunately kind of natural that we would see that overrepresentation in our population as well.”

Targeted efforts

Robinson said the decline in the city’s unhoused population was a result of targeted investments. Housing Forward’s rehousing program, known as the Dallas Real Time Rapid Housing Initiative, disbanded 11 homeless encampments and helped find homes for 1,871 formerly unhoused people since its creation in 2021.

Within the last year, Housing Forward received an influx of private and federal funding that the organization plans to use to serve and support 6,000 unhoused people by the end of 2025, Robinson said. Housing Forward has received $1.25 million from the Day One Families Fund, a private fund that works to reduce family homelessness. In February, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development awarded $22.8 million in special new funding to Housing Forward to target unsheltered homelessness. And in March, Housing Forward received $22 million in annual federal funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Mayor Eric Johnson announced in February the creation of a new volunteer task force composed of local homeless service advocates. The group will assess current policies regarding homelessness, research other plans to address homelessness and issue a report of recommendations to Johnson’s office by June 15.

The recent efforts to address the root causes of homelessness come after Dallas City Council passed an ordinance in October that made it a misdemeanor to walk or stand on a median that measures 6 feet or less. While city officials say the ordinance is meant to address public safety, others have said it seeks to criminalize homelessness by making it illegal to panhandle on medians. Panhandling is considered a free speech right, which is protected by the First Amendment, and the ordinance has led to a lawsuit against the city.

District 9 City Council Member Paula Blackmon, whose district includes Lakewood and parts of Lake Highlands, said she would still vote yes on the ordinance if it were to come to a City Council vote again. Despite the way some people perceive the ordinance, Blackmon, who serves on City Council’s Housing and Homelessness Solutions committee, said it is intended to keep people safe—the byproduct is that it may deter panhandling.

Despite the targeted efforts, some people who have experienced it say more must be done for sheltered homeless people.

Deosha Campbell, a single mother of four who previously experienced homelessness for about a year, said things like gas money, bus vouchers and affordable child care would help single moms like her keep a job.

Campbell and her children, who are all under 10 years old, moved from Sugar Land to Dallas to seek help from relatives after losing her job and becoming homeless in 2021. On the days they weren’t able to stay with relatives, they sought help from local shelters, Campbell said. Often, those shelters didn’t have enough space to house Campbell’s entire family for the night.

“There were shelters who wanted to split us up, but I wasn’t willing to do that,” Campbell said.

Eventually, Campbell found Interfaith Family Services, a Lakewood/Lower Greenville-area social services organization that connected her with resources, such as transitional housing and financial coaching. Still, Campbell said the city should do more to help others experiencing homelessness.

Lack of housing

Christine Crossley, director of Dallas' Office of Homeless Solutions, said the biggest roadblock to reducing homelessness in Dallas is a lack of affordable housing. In addition, Texas is one of two states that allows landlords to refuse to accept tenant vouchers, with the exception of veterans. If landlords were required to accept those vouchers, many low-income people on the brink of homelessness would be able to stay housed, Crossley said.

“All of us need affordable housing, regardless if you’re making $20,000 per year or $200,000 per year,” Robinson said. “If we’re relying on people’s hearts and minds to be changed before affordable housing is built, we’ll never build affordable housing.”

Blackmon said she would support new affordable housing developments in her district if they “make sense” for the area and its land use.

In the meantime, people who do support new affordable housing developments in their neighborhoods must be “just as vocal if not more vocal” than those who oppose such projects, Robinson said.

How to help

Blackmon and Crossley said housed residents should not donate money to people panhandling on street medians. Instead, they encourage housed people to donate money or volunteer time to local organizations and shelters.

“Let’s focus together on getting [unhoused people] out of the unsheltered place that they’re in,” Blackmon said.

By volunteering with organizations, Crossley said housed people can help connect unhoused people with not just small donations but resources to find more long-term help, such as financial coaching or job training. Then, unhoused people can learn where to go if and when they want to seek help.

Blackmon said she wants residents concerned about the state of homelessness to know that while it may not always seem like the city is actively working to reduce homelessness, the process of housing those who are unhoused takes time and careful planning. And the city is committed to reshaping its approach and taking that process one step at a time, she added.

“We are doing a lot. Could we do more? Probably,” Blackmon said. “We will get there, but what we’re trying to do is build a network, a platform, a system that then we can build the next layer on top of.”

Michael Crouchley contributed to this report.