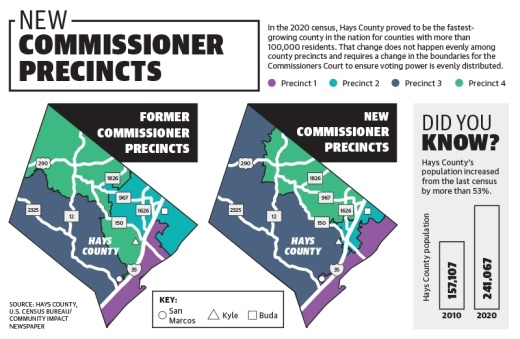

A new electoral map is set for the next decade, splitting San Marcos, Buda and Kyle along significantly different commissioner precinct boundaries than the prior map following the results of the 2020 census.

The Hays County Commissioners Court voted 3-2 on Nov. 9 approving the new map. Precinct 1 Commissioner Debbie Ingalsbe and Hays County Judge Ruben Becerra voted against the new maps that split San Marcos two ways instead of three. Both wanted more of downtown San Marcos and Texas State University tying into Precinct 1 boundaries instead of Precinct 3, which now stretches from San Marcos to Wimberley and to the northwestern corner of the county, according to the maps.

Precincts 2 and 3 divide Kyle, and Precincts 2 and 4 divide Buda.

“We were making sure that the county was aware of the huge population growth in Hispanic or Latinx voters in the northeastern portion of the county and that we believe that they had Voting Rights Act obligations to draw a precinct that would allow the Latinx community there to elect the candidate of their choice,” said Sarah Chen, a legal fellow with the Texas Civil Rights Project, one of several organizations that followed the county’s redistricting process.

Rearranging the county lines

Beginning in early 2021, the League of Women Voters of Hays County and other groups launched a campaign to petition the Commissioners Court to allow an independent redistricting commission, Chen said.

“The goal was to have redistricting taken out of the hands of elected officials to draw their own precincts instead to empower independent members of the community to draw those lines,” Chen said.

What the county did was a kind of compromise, Chen said. The court created a redistricting advisory commission, or RAC, that the Hays County chairs of the Democratic Party and Republican Party led, and also had members appointed by each member of the Commissioners Court.

“So it was still certainly quite political, and it only had the ability to advise the Commissioners Court about the ultimate maps. That being said, this [RAC] in its charter included having public hearings in each of the four precincts and having public mapping sessions,” Chen said. “There was this kind of commitment to some level of public input and transparency that I personally found laudable.”

The RAC came up with two map options to present to the court dubbed Map M9 and Map SM2. They were displayed on the Hays County website along with U.S. census demographic information and a public comment section.

Neither map received a vote on its own, however. Commissioner Lon Shell presented a different map he claimed to be informed by the RAC just a few days prior to the final Nov. 9 court meeting, a claim contested by others.

“It’s purely for a recommendation. There is no requirement that the court adopt a map or any other maps that are created by that advisory commission. It was just a body that was created by the Commissioners Court for the process,” Shell said. “I think the court’s idea is that we would be able to have a body that could have some public meetings, take public input and then provide recommendations to the court.”

Becerra said he thought the RAC process was inclusive and engaged the community in a way that would inform the court how to best balance voter interests. He did not agree that another map be drawn outside of the RAC’s purview.

“Instead, we had the old cliche politicians picking their voters, instead of voters picking their politicians. ... It’s an old philosophy that’s been running through this county government for many years,” Becerra said. “And they shamelessly produced the same results.”

Shell said the map he drew took about three days of work and he thought the map he drew—the one that was ultimately voted on and passed into law—solved problems of representation compared to the 2010 map.

“The map that was adopted [in 2010] was not very popular amongst many because it split up the city of Kyle and San Marcos into three commissioner precincts. And I felt that that was still very important in seeing those comments made during the public process for this redistricting. So I thought that trying to maintain those cities to not be split up into more than two precincts was a good goal, and that was one of the goals of my map,” he said.

Chen said the RAC approach “really looked like it could be a model for how other counties approach what normally is a very politically fraught issue of redistricting.”

Both maps are still available on the Hays County website.

“It felt like there was a less polarized approach by the RAC to a certain extent, and then the rug was pulled from under the RAC’s feet and the public’s feet at the very last minute,” Chen said.

Changes at the state and federal level

Statewide, altered Texas House of Representatives seats will change representation in Hays County as well as in Congress under new maps approved during the third special session of the 87th Texas Legislature and signed into law by Gov. Greg Abbott on Oct. 25.

Hays County will now be divided into state House Districts 73 and 45. Most of San Marcos, Buda and Kyle stay within District 45 boundaries, currently represented by Rep. Erin Zwiener, D-Driftwood, who will run for re-election.

District 73 includes the western half of Hays County and all of Comal County. Current state Rep. Kyle Biedermann, R-Fredericksburg, declined to run for re-election, leaving an open seat.Many local leaders testified at the Texas Capitol to advocate for keeping their communities together.

“On redistricting, I testified twice, once regarding the House and once regarding Senate districts, and I asked the redistricting committee please do not split our community,” San Marcos Mayor Jane Hughson said.

Hughson said she was concerned that some of the splits within cities on the congressional and state representative maps could mean some residents would jump between constituencies by just moving across town.

“The point that I was making is 70% of our people are renters. That means they move a lot and therefore ... you can’t establish relationships with some folks,” Hughson said.

Hughson was not alone in advocating for keeping splintering of the community to a minimum.

Two U.S. House seats were added to Texas due to 16% population growth over the past decade, according to census data. Each district must land within plus or minus 10% of the average size of a district if each had an even distribution of the population, according to the legal requirements listed on the Texas redistricting website.

U.S. Rep. Chip Roy, R-Austin, the incumbent for District 21, will run for re-election in that district, which now covers more of Hays County. This pushes District 25, currently represented by U.S. Rep. Roger Williams, R-Austin, out of the county.

District 35 will be represented by a new face as incumbent U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Austin, is opting to run in a new district in Travis County—District 37, which was created as a result of the total increase in state population.

“Hays County is in this weird position where it’s not getting any of the competitive districts that are associated with suburbs and exurbs in between Austin and San Antonio,” said Jesse Crosson, professor of political science at Trinity University in San Antonio. “Instead, it’s getting in these what we would call packed districts where you try to pack as many partisans as possible into the same district to make it safe for the incumbent,” he said.

Contesting the redistricting process

The political nature of the process is not reserved just at the local level. The process of creating the maps in the Texas Legislature brought resistance from various groups concerned the process would not result in an equitable reflection of where new population growth occurred in the state, said Miguel Rivera, a voting rights coordinator for the Texas Civil Rights Project.

“So we know that in Texas over the past 10 years, the state’s population grew by 4 million people, and that 95% of that growth was from people of color. And despite that, the maps ... don’t actively increase the districts that represent these new communities,” Rivera said.

Those allegations are in line with a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit brought against the state of Texas on Dec. 6 alleging “vote dilution,” or spreading voters of color around several districts to reduce their voting power. If that could be proven in court, it would be a violation of Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, according to the lawsuit.

“I think there was a tactic as a part of a larger strategy that we saw in gerrymandering from the state government this time around,” Rivera said.

While the redistricting process could also be challenged on a partisan basis, Crosson said that historically is a losing argument.

“The Supreme Court has consistently said, ‘while we don’t love the partisan stuff, it’s probably constitutional. You know, it’s just politicians being politicians,’ and the Supreme Court generally just tries to stay out of situations like that,” Crosson said.

Voter turnout in presidential elections is always higher in swing states than states not at risk for changing support of a political party, Crosson said. If more congressional seats are considered safe, he said it is less likely voters will show up.

“The bigger takeaway is we’ve got more safe districts, especially in this region, than we’ve had in a very long time ... In political science, we call it the case of vanishing marginals. There’s just fewer and fewer what we would call purple districts. That’s the direction it seems like Texas is headed—in the direction California is already in. So we shall see,” he said.

Zara Flores contributed to this report.