“Please let my kids, let all Round Rock students, have a normal year,” Farris said. “My daughter will be a junior and has never gotten to experience an authentic year of high school.”

A parent of a Round Rock High School graduate—as well as a high school student and a middle school student—Farris said not only has her daughter been affected by the mandates of the COVID-19 pandemic, but her son was also forced to give up an extracurricular activity during the 2020-21 school year to make up an education gap caused by remote learning.

Farris is one of many parents whose children experienced a loss of knowledge, or learning loss, as schools throughout the country took action to address safety concerns around the pandemic and shift to remote learning.

Now, officials at Austin, Round Rock and Pflugerville ISDs are working to address the learning losses that resulted from shifts to virtual learning or from lessons given that were not otherwise retained by students. Whether through the addition of new positions or additional tutoring for skills not mastered, districts are ramping up their efforts to close the learning gaps brought about by the pandemic.

Gauging learning loss

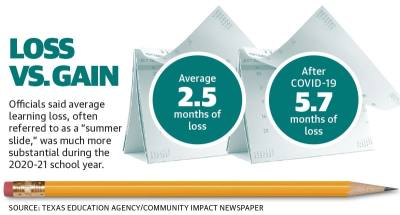

According to the Texas Education Agency, students in Texas on average experience 2.5 months of learning loss returning to school each fall. This means students typically forget 2.5 months’ worth of lessons taught by instructors each summer. According to the TEA, that amount of learning loss is normal.

Commonly referred as the “summer slide,” educators account for it each year by reviewing content from the previous year early in the current academic term.

However, experts say the normal gap in learning created by summer break was exacerbated by the abrupt departure many school districts made following spring break in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic became a nationwide concern.

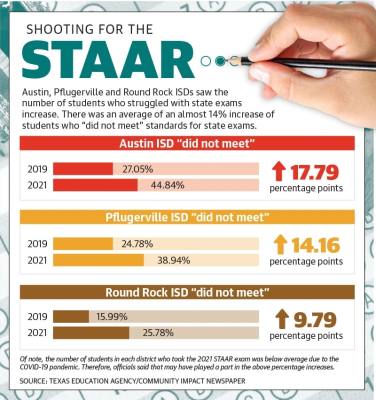

The TEA stated that the 5.7 months of learning loss resulting from COVID-19’s broad impact on the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years is exceptional. Examination of student results of the standardized exam known as the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, is one way to measure learning loss.

Ryan Smith, RRISD executive director of teaching and learning, said that while STAAR scores may not be the best indicator of performance as a whole, the district does not have another viable public metric. He said the district will present information regarding learning loss and its impact on teachers and students at future school board meetings.

“Our teachers are going to adapt and differentiate for each of their students as opposed to looking at some aggregate numbers,” Smith said.

In Austin ISD, even generally referring to the term “learning loss” itself is proving problematic for educators who do not want students starting the school year feeling they are at a deficit, AISD Assistant Superintendent of Academics Erin Brown-Anderson said.

“We’re trying to reframe it as, ‘We have all had an incredible experience over the last year, and we’ve learned things we wouldn’t have learned otherwise,’” Brown-Anderson said.

AISD, like districts across Texas, saw a higher rate of students fall short of grade-level expectations on the STAAR when compared to 2019, when the exams were last administered. AISD students performed poorer than the state average on math exams, as did middle school reading students.

However, these results are one of many data points used to gauge students, Brown-Anderson said. In the case of RRISD, school district officials also are looking at the participation rate of the most recent STAAR tests to better understand student performance, Smith said.

For example, in RRISD, 2,509 students on average took each STAAR exam in spring 2019. In spring 2021, a total of 1,491 students took the STAAR for an average reduction of 1,018 students, or 40.57% decrease per exam.

Where learning loss occurred

The exams that experienced the largest increase in students who did not meet grade-level standards in AISD were seventh and eighth grade STAAR mathematics. PfISD also saw its eighth grade STAAR mathematics scores see the largest increase in students not meeting grade-level standards. Similarly, the largest increase in “did not meet standards” in RRISD was for third-grade STAAR Spanish mathematics, with the caveat provided that the exam was administered to less than 70 students during both years.

While AISD did not see overall student reading scores as severely impacted, eighth grade reading fail rates increased by 21 percentage points from 2019 to 2021.

Some exams actually saw a reduction in the number of students who did not meet grade-level standards. In RRISD, there was a 38% reduction for fourth grade STAAR Spanish Reading and a 4% reduction in the English I end-of-course exam.

Starting in the classroom

Educators have identified a number of ways to address COVID-19-related learning loss and have been working to rectify the issue for the 2021-22 school year.

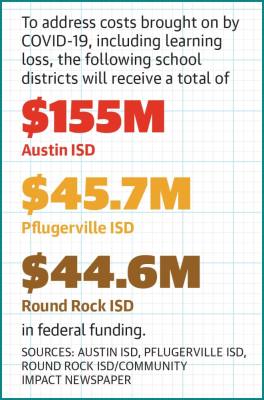

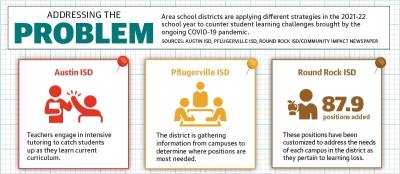

At RRISD, board members approved 87.9 full-time positions to combat learning loss and accelerate learning. RRISD underwrote funding for the additional staff through $4.3 million in federal grant money through the American Rescue Plan Act.

The new positions, which include additional middle and high school teachers, counselors and interventionists, were in the 2020-21 budget but previously went unfilled due to lower enrollment. Representatives from each RRISD campus provided feedback on what they needed to succeed in the coming year, Chief of Schools and Innovation Daniel Presley said at a July 15 board meeting.

“Some principals felt like they needed additional staff,” Presley said. “Because of certain situations, they needed smaller classes, and others, they were granted that. [We had] some other stuff like their class sizes were adequate, but they would rather have an instructional coach or other things they needed.”

Smith also said overall lessons will be more customized to the needs of each student through the district’s learning management system known as Schoology.

While RRISD has already identified which positions it is adding and how it is going to use them, PfISD is on a different timeline for making a decision.

The district has begun the process of gathering information for additional positions for the 2021-22 school year, funded by the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief III grant made available to states through ARPA.

It is unclear how many positions might be added to the district’s plan for the fall semester, but PfISD Chief of Academics and Innovation Brandy Baker said the district is receiving and considering requests from campuses to determine where the positions are most needed.

Once students are back on campus, Baker said the district will conduct benchmark testing to assess where students are academically. When the degree of learning loss can be determined, student-level data will show what areas of learning need to be addressed by educators during the school year, she said.

Caring for the ‘whole child’

As students make their way back to class at area school districts, physical health and academic performance will not be the only concerns. The districts also have amplified focus on social and emotional wellness.

RRISD describes this type of learning, such as managing emotions and developing concern for others, critical to a student’s engagement in school, according to the district’s website.

The district website cites multi-year research showing students who receive social and emotional learning had an 11% higher grade point average, less behavioral problems and higher commitment to school by the time they reached the age of 18.

In PfISD, similar priorities are outlined for students to learn these social skills in a manner that integrates with academic lessons, according to the district’s website.

And in AISD, Twyla Williams, director of counseling, said many students are experiencing trauma and grief due to prolonged absence from school campuses as well as February’s winter storm, which closed schools and businesses.

“We want to acknowledge where our students have been and where they are, and then where we want them to go,” she said.

As a result, AISD counseling staff will work with Brown-Anderson to check in on students on an emotional level in the course of regular classroom activities and integrate academics with emotional well-being in a focus on the “whole child.”

“They’re going to be readjusting, many of them to an environment they haven’t been in in a while. We talked to some students at the end of last year, and one of them said, ‘I hope they don’t expect us to remember how to have a conversation,’ and that really stuck with me.”