“The moment I wake up, I put on my GPS because that tells me the window of time I have to leave,” Melgar said. “If I take a few extra minutes [to leave the house], it delays my arrival time to work.”

Melgar said it takes him a little over an hour to drive each way to and from work. He estimates he drives 320 miles a week, putting gas in his car about every three days.

While Melgar said his dream job makes the commute worth it, he said he understands that not all members of the workforce in the Lakeway and Bee Cave areas are willing or able to make the long commute.

This problem, coupled with the high cost of living and housing in the area, has led to heightened labor shortages and calls for workforce housing to be built.

“The basic conundrum is that many of the people who work here can’t afford to live here. [People] who do work in the area have to commute very long distances to get here. That not only puts a dent in their quality of life, but [it] also increases turnover because after a while, that commute just gets to be too burdensome, and workers decide to look elsewhere,” said Ward Tisdale, executive director of the Lake Travis Chamber of Commerce.

In recent months, local leaders in both Lakeway and Bee Cave have worked to adjust city codes to make them more hospitable for multifamily developments, including workforce housing.

Additionally, the city of Bee Cave has taken steps to recruit a workforce housing development project on a piece of city-owned land. However, not all municipalities and elected officials feel they have the same role to play in providing affordable housing options to the area’s employees.

“In our past, this wasn’t ... something that people planned for because there really wasn’t a need for it. The population was much lower out here. The cost of living was lower,” Lakeway City Council Member Laurie Higginbotham said. “Now, all of a sudden, that’s changed. Things are getting built out. We only have so much land left available, and the need is huge for [workforce housing].” Housing hurdles

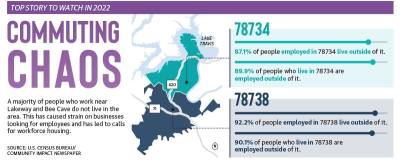

More than 92% of people employed in ZIP code 78738 and 87% of people employed in ZIP code 78734, which encompass Bee Cave and Lakeway, do not live in the ZIP code where they work, according to 2019 data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Similarly, about 90% of the people who live in both ZIP codes do not work within them.

Local officials said this discrepancy is caused in large part by the rising cost of housing and cost of living in the Lake Travis area, which has priced many middle-income earners out. The median sales price of homes rose over 35% from 2015-20, according to data from the Austin Board of Realtors.

“Many of the jobs in this area are service workers, teachers, nurses, first responders, those kinds of jobs, and many of those people just can’t afford to live here, so they have to commute,” Tisdale said.

Marco Alvarado, executive director of communications and community relations at Lake Travis ISD, said he sees a correlation between the area cost of living and the employment challenges facing both the district and the community. While he said hiring and retaining bus drivers and cafeteria servers has always been a challenge, the district is now having the same problems with teachers and aides. Alvarado said about 50% of the 1,400-person staff live within the district, while the other half commute.

“We’re hearing more and more of folks having to commute,” Alvarado said. “They may accept the position and tell us, ‘Yes, I can commute from 20, 30, or 45 minutes away.’ But a few weeks later after making that commute, they decide it’s just too much.”

Workforce housing aims to address employee shortages caused by shrinking nearby labor pools and long commute times by offering attainable housing options.

The Texas State Affordable Housing Corp. says workforce housing typically targets families making 60%-120% of the area median income, which in Travis County would translate to between roughly $58,000-$117,000 for a family of four, according to the city of Austin.

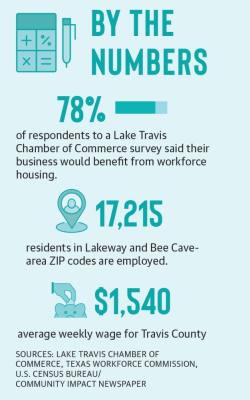

Of the respondents to a Lake Travis Chamber of Commerce survey, 78% said their business would benefit from workforce housing.

“This is a pretty critical situation, and doing nothing is not going to help the problem; we have to do something,” Tisdale said. Cities’ solutions

Heading into 2022, the issue of workforce housing has come before both Lakeway and Bee Cave city councils.

On Jan. 3, Lakeway City Council approved two new zoning regulations, one of which Mayor Tom Kilgore said would open the door for different housing options, including future workforce housing projects.

City Council created the R9 zoning category, which allows high-density developments up to 20 units per acre. Previously, the city’s highest density zoning code allowed for 12 units an acre. “That high density would allow an apartment building developer or a workforce project owner to come to the city,” Kilgore said.

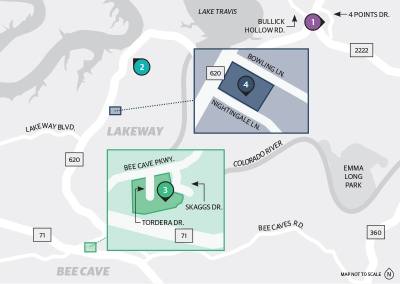

However, Lakeway City Council voted down a compromise measure offered by Higginbotham that would have brought a workforce housing development to a 7.6-acre parcel at the intersection of RM 620 and Nightingale Lane during a Nov. 15 meeting. The proposal would have allowed for a total of 152 units.

Kilgore, who voted against that development, said council had concerns about traffic on Nightingale, the size of the site and giving up potential commercial space on RM 620. At the time, Kent Conine of the Conine Residential Group, the developer behind the Nightingale proposal, said this was the city’s best location to build workforce housing, criticizing Lakeway’s restrictive zoning.

“Everything we do on council is about balancing competing interests that people have,” Higginbotham said. “Protecting and preserving the quality of life that our residents enjoy, but also sustaining our business community and making sure that they have what they need.”

Despite differing opinions on the Nightingale development, both Higginbotham and Kilgore said they believe there are other places in the city suited for workforce housing. While Higginbotham said Lakeway leaders have a role to play in identifying sites and developers, Kilgore said City Council must create a level playing field for all without cheerleading a specific project.

Meanwhile, Bee Cave officials are preparing to issue a request for proposals to developers who could build a workforce housing project to a 20-acre plot of land located on Bee Cave Parkway. City Manager Clint Garza said the city has a vested interest in supporting the business community because the majority of the city’s revenue comes from sales tax.

The business community has been supportive of bringing workforce housing, but Garza said some residents have concerns about increased traffic, the possibility of crime and misconceptions about workforce housing.

“When folks think about workforce housing, they start to think about things like Section 8 housing or full-on government subsidized housing that they may or may not have any experience with,” Garza said. “What we’re talking about is not that.”

Philippe Bochaton, president of Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Lakeway, said health workers are also at times priced out of the market and are unable to secure housing close to medical facilities.

“For those who work in the hospital, it’s often vital that they are close to the facility during on-call shifts when they are needed within minutes,” Bochaton said.

Working toward workforce housing

Lakeway City Manager Julie Oakley said while the issue of workforce housing is affecting the community, it is a broader Central Texas issue, and the solution must include all regional stakeholders.

“Working with regional partners is going to contribute to more success than the city of Lakeway on their own,” Oakley said.

Tisdale said as local leaders look into zoning changes and proposed developments, they should make changes that will create lasting solutions and account for future growth.

“No one anticipated this growth would be as large as it is, but it is, and we’ve got to think about the next 30 years, not just today,” Tisdale said.