With the burden of maintaining stability falling predominantly on moms, studies have found that they have had to sacrifice more of themselves in COVID-19 times than they did previously. While vaccine distributions offer a glimmer of hope to a post-COVID-19 life, for some Georgetown moms relief from the stressful year cannot come soon enough.

“I feel like it’s never ending. It’s going to end in April; it’s going to end in May; it’s going to end in June,” Georgetown mom Dana Martin said. “It just kept going and going and going, and we just have to roll with the punches.”

The added workload of having children home has led to about 2.5 million moms leaving the workforce since the start of the pandemic, U.S. Labor data shows, compared to 1.8 million men. But for Martin, not working was not an option as bills still need to be paid.

Martin works full-time from home, a perk she had prior to the pandemic, but she is also a mom of three young kids, two of which have special needs, and she takes care of her disabled uncle who lives with them.

Martin works full-time from home, a perk she had prior to the pandemic, but she is also a mom of three young kids, two of which have special needs, and she takes care of her disabled uncle who lives with them.Her two oldest kids sit at the dining room table completing virtual school work while her toddler sits in her highchair next to her. Laid out beside her work laptop is a large, perfectly outlined and color coded planner that breaks down her days, listing all the doctors, therapy and tutoring sessions, as well as extracurricular activities she has to get her family to.

Her husband, who was temporarily unemployed over the past 12 months, goes to work. Martin squeezes in emails and phone calls when she can.

Her husband, who was temporarily unemployed over the past 12 months, goes to work. Martin squeezes in emails and phone calls when she can.“I’m trying so hard to be a professional employee throughout the day, but I’m not really getting anything done,” Martin admits. “I’m constantly shuffling [between] everyone’s needs.”

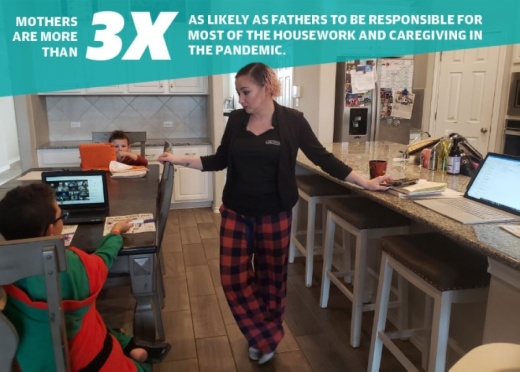

According to research by Catalyst, a nonprofit that works to accelerate women in the workplace, 71% of moms have modified their work routine to adapt to caregiving responsibilities, compared to 65% of dads. Mothers are also more than three times as likely as fathers to be responsible for most of the housework and caregiving during COVID times, according to McKinsey & Company research.

“I feel like I’m literally the only one who has kept it solid this whole time,” Martin said.

Doing it all

Moms already take on much of the household work, but that was exacerbated by the pandemic, data shows.

McKinsey & Co. research found that during COVID, mothers are 1.5 times more likely than fathers to be spending an extra three or more hours a day on housework and child care—equivalent to 20 hours a week, or half a full-time job.

Brianna Briggs is a first-time mom who had her daughter six weeks before the pandemic. She also cared for her seven-year old sister, helping her with virtual learning.

Brianna Briggs is a first-time mom who had her daughter six weeks before the pandemic. She also cared for her seven-year old sister, helping her with virtual learning.Briggs said the hardest part of the pandemic was not being able to do all the things she imagined she would do as a first-time mom, such as making friends with other moms and taking her daughter on play dates.

Her husband is also an essential worker.

“[Moms] are the ones that have to take on everything. We take on our spouse’s health; we take on our spouse’s duties. We have to worry about our children, worry about our parents, worry about our grandparents,” Briggs said. “It’s made it to where we’ve had to worry about a lot more to make sure that everyone’s happy and healthy.”

Corren Kopp said her husband is also an essential employee working as a firefighter paramedic.

Kopp said even with the department’s strong safety measures she cannot get rid of the fear in the back of her mind that he will test positive with the disease after interacting with the public.

Kopp said even with the department’s strong safety measures she cannot get rid of the fear in the back of her mind that he will test positive with the disease after interacting with the public.She also works from home as a wedding planner, an industry that was crippled by the pandemic, as she raises three young kids.

“I’m just trying to get things done, “ Kopp said. “I find myself doing more work just at night when they’re sleeping and having to stay up late.”

In fact, 61% of mothers and 55% of fathers said they work outside of care hours in order to balance other family responsibilities during the pandemic, according to Catalyst research.

Kopp added balancing mom and professional duties has her feeling pulled in every direction.

“I feel like I’ve been a chauffeur and a personal assistant and in charge of their schedules and doing everything even more than usual,” she said. “It’s been stressful.”

The sentiment was shared by Anna Kraft, a Georgetown mom of two young boys.

The sentiment was shared by Anna Kraft, a Georgetown mom of two young boys.A photographer by trade, Kraft said she closed her studio on the Georgetown Square due the pandemic. She said her business really took a hit last spring as appointments were often canceled, but the experience forced her to think outside of the box including in childcare. Kraft said and her husband arranged a childcare schedule so she can have blocked off time to work without interruption.

“The hardest part is working from home with little ones because you can’t anticipate their needs 100% of the time,” she said.

Raising kids with special needs

For Georgetown mom Allison Wright, putting everyone’s happiness before her own led her to go most of the year without seeing her son.

Wright’s 12-year-old son has special needs. As a single mom, Wright said her parents who live in Leander often help her, with her son and dad becoming best friends.

In March, she sent her son to stay at her parent’s house for spring break since they have several acres of land and plenty to keep her son preoccupied. But seven days turned into nine months when the pandemic continued to linger longer than she anticipated and she and her parents decided her son would have a lot more to do on large property then stuck in her apartment.

Wright also continued to work and with her parents being high-risk, she thought it best her son stayed to keep her family safe, healthy and happy.

“It was hard, but I’m not sorry that I did that because mental health wise [my son] wouldn’t be okay not seeing my dad for that long and my dad wouldn’t be okay not seeing my son for that long,” Wright said. “It’s not like other moms who experienced job loss, financial issues, and issues with homeschooling. I was the mom who sent [her] son away trying to shelter her family.”

“It was hard, but I’m not sorry that I did that because mental health wise [my son] wouldn’t be okay not seeing my dad for that long and my dad wouldn’t be okay not seeing my son for that long,” Wright said. “It’s not like other moms who experienced job loss, financial issues, and issues with homeschooling. I was the mom who sent [her] son away trying to shelter her family.”Georgetown mom and trauma therapist Charlotte Crary has two kids with special needs. When schools were closed she said her son received little to no services from the district, setting him back in his education and he began acting out.

“My husband’s job was suffering. I was having to cancel my therapy sessions to take care of [my son], and it was really tough to balance,” she said.

Her husband Peter Crary said the pandemic stopped his work travel allowing him to do more school pick-up and drop-off, but he had to block off time during the work day to do so. He added he also had to adjust to his kids making noise in the background of his work calls.

Eventually, Charlotte Crary said she and Peter Crary made the difficult decision to send her son back to in-person school so that he could receive the services he needed.

“I’m not an occupational therapist; I’m not a speech therapist; and I’m not a teacher. All of a sudden, I had to be all of those things,” Crary said.

Working mom guilt

Research by Catalyst, found since the start of the pandemic, mothers are reporting higher rates of increased anxiety than fathers, feeling more guilt for their inability to help kids with the school work or to be working when they should be attending to caregiving.

About 78% of mothers reported feeling nervous, anxious or on-edge for several days or more over the last year compared with 69% of fathers, Catalyst found.

Georgetown mom of three Emi Garcia was working from home but the demanding job required to be at her desk all day. She thought she was balancing the work from home life until a Georgetown police officer arrived at her door informing her that her son was not attending virtual classes. It was then she learned her son had learning difficulties and could not complete virtual classes on his own.

Georgetown mom of three Emi Garcia was working from home but the demanding job required to be at her desk all day. She thought she was balancing the work from home life until a Georgetown police officer arrived at her door informing her that her son was not attending virtual classes. It was then she learned her son had learning difficulties and could not complete virtual classes on his own.“I finally had a meltdown,” she said. “I just couldn’t work and help my child, and I felt like a bad mom.”

Georgetown mom of two and local business owner Mai Lan Bradford said she too learned of her son’s learning difficulties during the pandemic and felt guilty that she was failing him.

Georgetown mom of two and local business owner Mai Lan Bradford said she too learned of her son’s learning difficulties during the pandemic and felt guilty that she was failing him.She said her son, who does well in all of Advanced Placement classes, struggled to complete his coursework when classes went virtual. Then, Bradford said she had a hard time trying to help him.

“I was trying to keep my businesses running, but I felt so guilty I wasn’t at home helping my son navigate through the new reality of school. It’s just been hard juggling all that,” she said.

Georgetown counselor Rachel Saenger said she has seen an increase in stress, anxiety and even depression among her mom clients since the start of the pandemic.

“Moms are struggling with just a lot more transition, and a lot more that they are responsible for,” Saenger said.

She added that she has also had an uptick in parents who are seeing mental health issues within their children and are unsure of what to do.

“That’s been really challenging for moms to know how to navigate through when they’ve had a child who hasn’t really had any noticeable mental health issues before, and then suddenly with loneliness, isolation or worry about the pandemic, they do,” she said.

To help overwhelmed moms, Saenger recommends parents find a moment of relaxation where they take deep breaths and practice mindfulness by grounding themselves in their five senses.

She also recommends moms schedule dedicated time to be alone or engage in self-care, and talk their stress out with a trusted friend, family member or therapist, who often have advice through a different perspective.

“I’m a mom myself and I know how hard it can be when things get really busy to actually go out and do something some weeks. So just take that moment, and [practice] self-care, I think is really critical,” she said.