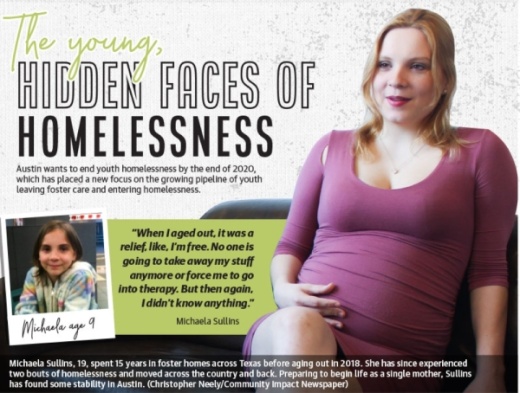

But in the house where her sister lived, Michaela said secondhand methamphetamine smoke regularly filled the air. Almost as quickly as she arrived Michaela fled to a friend’s place in Austin and, like many homeless young adults, couch surfed while trying to find stability for her and her unborn daughter.

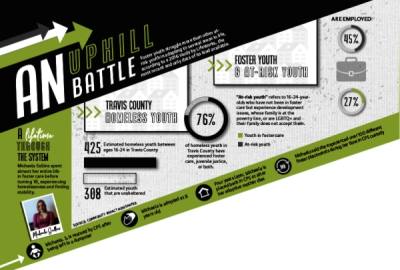

Now, four months later, Sullins lives in public housing and meets regularly with a caseworker from the local nonprofit LifeWorks. She has a job, and her due date is set for late March. Sullins and her caseworker admit finding housing so quickly was a “miracle.” However, her struggles with homelessness following a lifetime in the foster care system were not as improbable. Nationally, more than 25% of foster youth experience homelessness within two to four years of leaving the system.

In Travis County, 37% of homeless young adults between 16 and 24 years old were in the foster care system. At the end of this year, Austin wants to become the first city in America to effectively end youth homelessness. A local campaign is underway to build an intervention and response system that ensures youth homelessness is rare, brief and nonrecurring.

Whether that goal is possible is a point of debate in among service providers and experts in the field. Even as a top priority, some say limited resources and the complexities of youth homelessness make the 2020 deadline unrealistic.

However, officials, experts and service providers agree ending youth homelessness requires Austin to address the growing pipeline of children aging out of foster care and ending up on the streets.

Addressing a ‘system failure’

As her 18th birthday approached, Sullins anxiously awaited the decision coming her way. As a legal adult, she could choose to voluntarily continue under an extended foster care system for another three years or leave. After a lifetime in Child Protective Services and more than 100 home placements, Sullins was done with the system.

“All my life [I looked forward to leaving]; I was counting down the days in my journal,” Sullins said. “I just didn’t want to be controlled anymore. I wanted to go out into the world and do what I wanted.”

She entered a transitional home aimed at instilling life skills, but Sullins admits the change was tough. Within months she experienced her first bout of homelessness.

Will Francis, executive director of the National Association of Social Workers’ Texas chapter and member of the Travis County Child Protective Services Board, said most young adults like Sullins follow a similar path.

“Almost all kids just look at you when you offer them extended foster care [at 18] and say, ‘This same system that has been the biggest burden of my life is now the solution to my problem? No way,’” Francis said. “That to me is one of the giant red flags. You have a safe support system that includes housing, and kids are rejecting it and instead they’re staying on couches and ending up completely homeless.”

Travis County District Judge Aurora Martinez Jones focuses exclusively on CPS cases. She concurred that most who age out want to be done with the system. There are some, though, who want to take advantage of the services offered by extended foster care; however, she said limited capacity, especially in Travis County, means they have to choose between being placed outside the county or entering adulthood on their own.

“It’s heartbreaking to see that situation because it’s just 100% a system failure,” Martinez Jones said. “That’s when our kiddos are getting lost into homelessness. We lose track of them. ... And sometimes I never see those kids again.”

Difficulty keeping track

Martinez Jones said from her bench, the issue of foster youth aging out and entering homelessness increases parallel to the area’s population growth; however, many in the field say data collection is lacking, which makes it difficult to holistically measure the problem and the impact of solutions.

Susan McDowell, executive director of LifeWorks, said although organizations can measure immediate outcomes, “We can’t tell you have these kids fare four years later. It’s on our wish list, though.”

Eric Byrd, a caseworker with the SAFE Alliance, a local nonprofit that offers transitional living and extended foster care services, said although they have success discharging youths into independent living situations, there is little followup.

Erin Argue, director of support services with Partnerships for Children, a local organization that matches former foster youth with mentors, said the lack of data is a major issue.

“[The exiting youth] can identify somewhere to live ... or a job they have. ... But those numbers don’t tell you what’s actually happening,” Argue said. “It’s being able to sustain and maintain that [living situation or job] for any duration of time that really becomes the issue.”

Francis said tracking clients after they leave care becomes difficult with young adults.

“We don’t really know what the scope of the problem looks like,” Francis said. “That reflects back to the point that Austin wants to end youth homelessness by 2020. Do we really know what we mean by that? ... I don’t think we’re very honest about the long-term success rate for some of this stuff.”

Fixing the pipeline: A pipe dream?

McDowell said the effort underway in Austin is the only one of its kind in the United States and that Austin will be “trying to write the how-to manual.”

She said ending youth homelessness does not mean no more homeless youth. Rather, she said, it is about building a system and capacity to make youth homelessness “rare, brief and nonrecurring.

“We have to do a lot of front-end work to address housing and supporting the needs of youth who are at risk of homelessness—we need to slow the pipeline into homelessness,” McDowell said.

McDowell said the service provider community is “aggressively” working to contact any youth who are homeless or at risk of homelessness as they touch the local services system, such as applying for rental assistance or checking in at a shelter. It is part of the initiative’s key “diversions” strategy. McDowell said word of mouth is also crucial. When Sullins arrived in Austin, she became connected with LifeWorks after hearing about it through her church.

Francis and Argue contend the goal is too ambitious, and the issue too complex to harness by the end of the year. Argue called it a “behemoth of a mission.” Francis said the current response system needs to evolve beyond assuming everything is solved because the youth are in housing.

“We really need ... focus on how these kids have connections to adults and positive people in their lives who are going to be there to support them when they really need help,” Francis said. “If you just put someone in a house and don’t address workforce and mental health and health care needs, the housing is probably not going to stay.”