Clear, who is studying to get her master's degree in public health from UT Health, got connected to the effort through a professor and started in March, before there were many reported cases of COVID-19 in the area. On her first day, the public found out about a group of UT students who contracted the virus on a spring break trip to Mexico.

Today, Clear and the team of about 150 volunteers have developed more efficient processes to get in touch with individuals who had contact with someone who tested positive, to gather information, to encourage self-isolation and to attempt to box in the virus. They work in six-hour shifts, either from 8 a.m.-2 p.m. or 2-8 p.m., and Clear said they handle about 30%-35% of positive cases in the area. Austin Public Health is responsible for the rest.

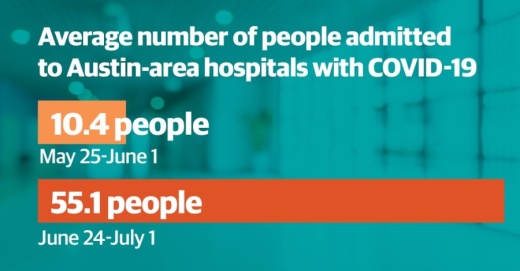

But over the last two weeks, as the number of confirmed cases in the Austin area have continued to soar, the job has gotten harder for the volunteers. Travis County surpassed 10,000 total COVID-19 cases July 1. More than 3,000 of those cases have been reported in a period of just five days.

"The surge of cases has been difficult for us in terms of workload," Clear said. "That's definitely been a new difficulty we've encountered in the past few weeks."

Dr. Darlene Bhavani, an epidemiologist with Dell Medical School at University of Texas who oversees the contact tracing program, said contact tracing needs to be a part of a larger community and individual effort in order to effectively reduce the spread of the disease.

Bhavani said those individual efforts include staying home as much as possible, wearing a mask and keeping 6 feet of distance, but she also said businesses and employers can play an important role by allowing workers to stay home when sick and instituting safe practices.

"We can’t just rely on contact tracing and keep up. It is still effective; it will limit some transmission; but it won’t bring us down to the numbers that are acceptable. We need other strategies in place," Bhavani said.

'We simply can't test everyone'

Volume is not the only challenge facing APH when it comes to contact tracing. Technology also plays a role, according to Dr. Mark Escott, Austin-Travis County interim health authority.

Escott told Travis County commissioners June 23 that cases are still coming into APH from health providers by fax machine, leaving APH staff to sift through the case results manually.

"Across the state and across the country, this is a very manual and archaic process. We're struggling with that," Escott told commissioners.

Meanwhile, demand for testing has skyrocketed, leading to a further backlog in testing results that hampers public health officials' ability to contact trace in a timely fashion. Escott said over the week of June 24-30, APH, clinical provider CommUnityCare and Austin Regional Clinic provided about 11,000 COVID-19 tests.

CommUnityCare alone has provided more than 18,000 free tests to the community since March. In a media release, CEO Jason Fournier said the health provider cannot keep up with current demand.

"Our drive-up testing sites open at 6:30 a.m.; however, on Monday [June 29], we were at capacity before we opened. We want to continue testing those with nowhere else to go, but we simply can't test everyone," Fournier said.

At APH's testing sites, data presented by Escott to Travis County commissioners June 30 shows about 5,500 free tests were conducted between June 15-28. With demand so high and antiquated technology being used to keep up, Escott said results were coming back seven to 10 days after a test, meaning the investigation would begin after the coronavirus patient had already passed the point where they were at risk of spreading the disease.

"The concept of doing a case investigation and contact tracing on someone who is likely no longer infectious is a waste of time. What we’re having to do is reprioritize both our contact tracing and testing strategy," Escott said.

On June 26, Austin Mayor Steve Adler announced in a Facebook Live video that the city's public testing sites would no longer be providing tests for patients who are asymptomatic. CommUnityCare has adopted the same policy, and as of July 1, both entities are encouraging people with health insurance to seek testing through their health care providers. The goal of these policies is to free up space at the testing sites for people who do not have insurance.

Meanwhile, the tracing strategy has shifted as well. Escott said APH staff, by necessity, are now focusing on those tested most recently in order to quickly get in touch with their contacts and have the greatest impact. Bhavani said UT Health Austin volunteers have adopted a similar policy.

"We’ve tried to prioritize cases close to symptom onset, so we can be more timely with investigations and contact," she said.

As officials scramble to trace the paths of the virus and contain it, hospitals in the local area still have room for patients, but the exponential growth of cases is causing concern among officials about what capacity will be a few weeks down the line.

According to Ascension Seton, Baylor Scott & White Health and St. David's HealthCare, staffed hospital beds in the Central Texas area for the three major hospital networks are about 72% occupied, and ICU beds are about 80% occupied.

Those capacity numbers are typical, Escott said, but if the Austin community and other large cities in Texas cannot rein in the uncontrolled spread of the virus, the beds will quickly fill up, and there will no longer be enough nurses and doctors to treat patients.

"We have to catch up. We have to get back to the situation where we can track where a disease came from," Escott told commissioners June 30. "Right now, we can’t because there’s simply too much disease spread right now."