“My team has been coordinating very well with both county and the state,” Missouri City City Manager Odis Jones said. “I think what’s been the issue over the last [few] months has been our ability, collectively, ... to be able to get vaccinations on a frequent basis.”

Jones also said with the increased number of vaccinations becoming available, the addition of a megasite to the city and the increased vaccine supply to at least two Missouri City vendors, he thinks the city might be headed in the right direction. As of March 5, Fort Bend County has had 51,323 cases of coronavirus, resulting in 511 deaths.

“I think things might get better,” Jones said. “We’re starting to see an uptick in terms of quality and consistency of service coming from the [federal government] to make sure that we’ve got adequate vaccination sites.”

Other local officials agree that distribution is headed in the right direction.

“We’re at the cusp of getting many more vaccines in the community, and we’re positioned to push those out,” said Dr. Jacquelyn Johnson-Minter, director of Fort Bend County Health and Human Services. “If there’s another surge, we should be able to blunt it. ... We should be able to blunt it—if we’re continuing to hammer on the vaccines.”

As of late February, officials said they were hopeful vaccinations of the general public could begin as soon as early spring. However, challenges remain when it comes to getting vaccines to underserved and vulnerable populations, including those who lack information about the vaccine, leading them to not trust it, and those who lack access to transportation.

“We want to make sure that we have adequate distribution sites in those impacted areas where they are particularly hit hardest,” said state Rep. Ron Reynolds, D-Missouri City. “I have already had to do some demystification and debunking—some distrust. ... It is something that we’re proactively working on to take away those false narratives, you know, misinformation.”

Fort Bend County officials said they are distributing the limited number of vaccines they are supplied as quickly and efficiently as they can, but public health advocates said it will become increasingly important for outreach to improve and for systems to be in place to reach those groups.

“I’m worried that we are just going to see a replay of that same movie that we’ve seen again and again,” said Dr. Mollyann Brodie, executive vice president and chief operating officer with the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit focused on health policy issues. “[A] new vaccine comes, and then two to three years down the road we look back, and we ask why the mortality rate is still higher in these populations. We come back and figure out that nobody went to them in a concerted and sustained way.”

Successes, challenges

Those eligible for vaccines in Texas in the first two phases include front-line health care workers, long-term care residents, people with certain medical conditions, individuals over the age of 65 and, as of early March, teachers and child care workers. State officials estimate roughly 300,000 people fall into those categories in Fort Bend County—just under 50% of its residents over the age of 16.

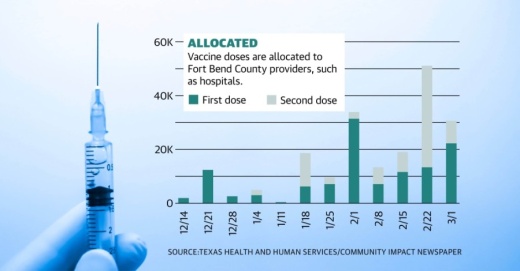

As of March 3, just over 200,000 vaccines had been distributed to more than 65 different locations in county, including local hospitals, clinics and pharmacies. The vast majority have been distributed by the Fort Bend County Health Department and Memorial Hermann Sugar Land.

Over 120,000 people had received at least one dose of the vaccine in Fort Bend County as of March 2, and 70,882 vaccine recipients have received both doses and are fully vaccinated, according to Texas Health and Human Services. With vaccine supply still limited and largely concentrated in the medical center, some Sugar Land and Missouri City residents have expressed frustration in the registration process.

“I am lucky because I am a patient at MD Anderson and I was able to get the vaccine through them,” Sugar Land resident Lucy Leal said. “I did try to get it through Fort Bend County before [MD Anderson] offered it to me, but by the time I’d see [vaccines were available] all the slots would be taken.”

Svenya Elackatt, a Missouri City resident who was pursuing the vaccine for her father, said she had a similar experience with registration filling quickly.

“The one thing is you need to be sitting in front of the monitor when they open access so you can sign up,” Elackatt said. “It filled up fairly quickly.”

Looking ahead

Officials at the local and national levels have stressed the importance of ensuring people are not overlooked in the vaccination process for reasons beyond their control, including cost, a lack of transportation or a lack of information about the vaccine. Racial equity has also been at the forefront of those conversations.

Communities of color have been hit especially hard by the pandemic, suffering a disproportionate number of the cases and deaths, said La Vonia Cannon, a former pharmacist who now serves as the regional director of Walgreens stores in the Greater Houston area. For that reason, it is even more crucial that those communities are covered in vaccine efforts, she said.

The Texas Department of State Health Services has contracted with Walgreens to help distribution, Cannon said, and the chain has administered about 52,000 vaccines statewide as of the end of January. Part of the reason Walgreens was chosen for the partnership was its ability to reach those underserved communities, Cannon said.

“Being in these communities of color that are socially underserved, we’re able to build those relationships I think a lot more strongly, and they’ll be more long lasting,” she said. “With that relationship, we’ve seen [pharmacists] provide a lot more one-on-one education.”

The pharmacy chain launched a partnership Feb. 9 with the ride-hailing service Uber through which people who lack transportation can get free rides to vaccine appointments, Cannon said.

Aside from transportation issues, part of the challenge of reaching underserved communities has to do with education, Brodie said. People who do not understand how vaccines work or why they are important are less likely to seek them out and more likely to be suspicious, she said.

If outreach to those communities is lacking or if vaccine sites are not located within them, Brodie said people who otherwise could have been swayed to get vaccinated would end up missing out.

“There’s a large share in the movable middle, and they very much want to see what happens to those who take the vaccine ahead of them,” Brodie said in a Feb. 18 virtual panel.

In an online survey about vaccine confidence conducted by the University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs, people who identified as African American and Latino were more likely to fall into categories that suggest they were undecided about the receiving the vaccine.

The survey, conducted between Jan. 12-20, garnered 1,329 responses. About 14% of African Americans and 11% of Latinos said they would “probably not” get vaccinated, compared to 10% of white people. Meanwhile, about 15% of African Americans and 10% of Latinos said they were unsure, compared to 9% of white people.

White people made up the majority of survey respondents who said they “definitely would” or “definitely would not” get the vaccine.

“The only constituents that I’ve had that have been very skeptical have been African Americans,” Reynolds said. “I haven’t encountered that with any other population yet.”

Reynolds also said the mistrust from the African American community is not baseless but instead is rooted in the country’s history of medical abuse toward Black Americans. One example Reynolds cited was the 40-year Tuskegee experiment, when the U.S. Public Health Service intentionally infected hundreds of Black men with syphilis under the guise of treatment and then left the infections untreated for decades despite identifying penicillin as an effective antibiotic.

“We don’t believe that there’s any evidence of anything nefarious,” Reynolds said. “We are trying to put out positive information—factual information, scientifically backed information—to dispel those myths."

As the vice chair of the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, Reynolds said he made a point to lead by example by publicly receiving the vaccine on Facebook Live.

“We’re trying to show by example that we believe that this is safe and it’s effective,” Reynolds said. “It is not something that is going to do harm to you. We believe that resources have to be put out there to get public information out there and to dispel those concerns.”