On May 15, some areas of League City received over 5 inches of rain in about one hour, making it one of the heaviest rainfalls the city has seen since voters in May 2019 approved a $73 million bond for numerous drainage projects around the city.

The flooding residents endured was worrisome. Several residents from flood-prone subdivisions showed up at League City City Council’s May 26 meeting to voice concerns.

“Every time we have a hard rain ... [we’re] just waiting for our houses to flood. It doesn’t take a hurricane anymore,” The Meadows resident Ruth Thompson told City Council. “We have become the dam, and it’s like a swimming pool.”

Now, the entire Bay Area is facing what meteorologists expect will be a more active hurricane season, all during COVID-19, which adds new wrinkles to preparation and response, officials said.

“We can do all the planning in the world, but Mother Nature is going to ... dictate how we respond,” said Cory Stottlemyer, public information officer for the Houston Office of Emergency Management.

Active season

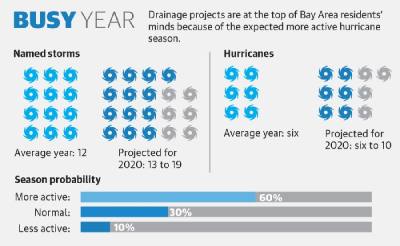

Hurricane season is generally June through November. Typically, meteorologists expect 12 named rainstorms, of which six could become hurricanes, to form in the Atlantic Ocean during these months.

For the 2020 season, meteorologists expect to see 13 to 19 named storms, of which six to 10 could become hurricanes, said Dan Reilly, League City meteorologist at the National Weather Service Houston/Galveston Office.

Contributing to the more active season are warmer Atlantic waters, reduced wind shear and other factors. The busy season could be a concern for some, Reilly said.

“More storms developing means a greater chance one of them will hit us,” he said.

However, a more active season is not a guarantee a major storm will make landfall in the Bay Area.

“It’s best to prepare every year no matter what the forecast,” he said.

Ryan Edghill, League City’s emergency management coordinator, agreed. Throughout history, there have been major hurricanes that have hit the Texas Gulf Coast during quiet seasons and active seasons when the Bay Area did not see any major storms, Edghill and Reilly said.

“I try not to put a whole lot of weight into the seasonal forecast. It only takes one storm,” Edghill said. “We have a probability every single year of getting hit by a storm, and I tell people that’s part of life living on the coast.”

Prepping during a pandemic

Still, officials are taking what they learned from Hurricane Harvey and what they know about COVID-19 to prepare for the busy season.

When a hurricane hits the Texas coast, cities have two options for their residents: sheltering or evacuating.

Being so close to Galveston Bay, League City—along with many other municipalities in Galveston County—is an evacuating community, City Manager John Baumgartner said.

However, Hurricane Harvey was atypical in that it did not include the high winds and other factors that make hurricanes deadly, so the city did not evacuate. Instead, the hurricane was a heavy rain event that dropped dozens of inches of rain on League City and basically surrounded the city with water, Edghill said.

“We were pretty close to an island for a long time,” he said.

Harvey taught League City officials the importance of resource and logistics management, Edghill said.

During emergency flooding, League City has “lily pads,” such as schools where residents can shelter temporarily until they can evacuate or move to a more permanent shelter. Since the record-breaking hurricane, the city has established more potential lily pad sites and strengthened its relationship with Clear Creek ISD and the Red Cross so resources such as cots and water can be more readily available when another storm hits, Edghill said.

Before Harvey hit, League City officials were projecting 20 to 30 inches of rain, and they got “complacent” and did not set up the city’s emergency operation center as early as they should have. Since then, they have been more vigilant and proactive with emergency management group training and other efforts to make sure the city is ready ahead of time, Baumgartner said.

Officials said a new challenge with this season is the introduction of the coronavirus, which has led to a global pandemic and changed daily life since it hit Texas in March.

Stottlemyer said Houston used high-water vehicles to rescue residents trapped in flooded homes during Harvey. In a worst-case scenario, city officials will prioritize the lives of those who need immediate rescue, even at the risk of spreading the coronavirus, he said.

“[Rescuers] are gonna put life safety first and foremost,” he said.

That is not to say, however, that emergency management officials are being careless when it comes to the coronavirus.

Typically, during a hurricane, emergency officials will admit residents who need shelter into large, open buildings. Officials are looking at ways to maintain social distancing and protect employees and residents during such events.

One idea is to install plexiglass shields between residents seeking shelter and employees registering residents into shelters. Residents who are symptomatic could be isolated from the main group, Stottlemyer said.

Both Houston and League City officials are considering using “non-congregate” shelters, such as hotels or dorms, to keep people separated. If League City were to shelter people, each resident would get 110 square feet of space instead of the typical 40 square feet, per Red Cross guidelines, to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, Edghill said.

“If you had to pick between a week of unknown exposure to COVID[-19] or not sheltering them, we’d put people in the shelter, unfortunately,” Baumgartner said.

There are several state-supported evacuation hubs in the area. Typically, officials would load 50 people onto buses to evacuate from these hubs, but they will limit buses to about one-third of that amount in light of the pandemic, Edghill said.

During water rescues, residents will be placed in open-air vehicles, and fresh personal protective equipment will be waiting for them at whatever shelter they are dropped off at, Stottlemyer said.

Drainage projects

While making sure the Bay Area is ready for another hurricane, League City officials are also progressing drainage projects aimed at reducing neighborhood flooding in the interim. League City officials recognize every day that passes without proper drainage is another day residents are at risk for their homes being flooded, and they are working to advance 21 planned drainage projects.

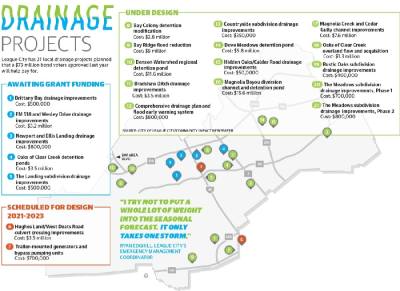

Of the 21 projects funded by the $73 million bond, 12 are under design, two will soon be under design, five are eligible for grants that prevent design work from taking place until grants are awarded, and two are scheduled for design in 2021 through 2023. City Council has directed staff to accelerate these projects and have them all under design by the end of the year, Baumgartner said.

Typically, it takes a year to design a project, another year to acquire land and another year for construction. Additionally, the city cannot do all drainage projects simultaneously, especially with several road projects underway, Baumgartner said.

“None of it’s moving as fast as we want it to,” Baumgartner said.

This fall, contractors will begin on two of the four flood-reduction projects in the Bay Ridge subdivision. The first two projects will add a 42,000-gallon-per-minute stormwater pump to the neighborhood’s existing detention pond and overflow wales at certain roads to allow for stormwater outfall into the pond.

Sarah Greer Osborne, League City’s director of communications and media relations, said the city had planned to start construction in May, but COVID-19 put those plans on hold. The heavy rain in mid-May brought the issue back to people’s minds, she said.

“It’s kinda all coming together,” Osborne said.

Officials started with drainage projects in Bay Ridge, Oaks of Clear Creek and The Meadows because those subdivisions have suffered the most from flooding over the years. Those from The Meadows voiced urgency at City Council’s May 26 meeting, and Baumgartner told them their neighborhood is next on the list, he said.

Over the years, the city has tried diverting flow, maintaining drainage ditches, and mowing and clearing outfalls, but for some areas, this has not been enough, Baumgartner said.

“They’re not easy problems to solve, or we would have solved them years ago,” Baumgartner said. “As a city we can’t quite control everything.”