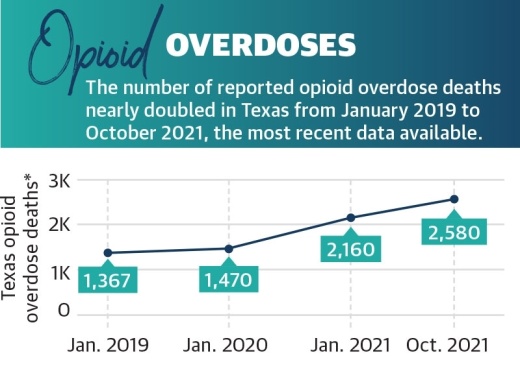

Information from the Texas attorney general’s office indicates drug overdose deaths had increased by around 32% in 2020 from the previous year, driven primarily by opioids. Additionally, provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics showed opioid overdose deaths nearly doubled in Texas from January 2019 to October 2021, and there was an additional 30% increase in deaths from October 2020 to October 2021, the most recent data available.

“These are diseases of despair that we’re dealing with,” said Tyler Varisco, a health services researcher with The University of Houston. “When people are economically challenged or psychologically challenged as many of us have been over the past two years, we see increased vulnerability in our communities to opioid use and other forms of substance misuse.”

With increased isolation and financial stresses, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated struggles against the opioid epidemic in Texas. Recovery treatment transitioned into less effective online services, and access to quality treatment, such as medication, became more complicated, according to local experts.

Opioid usage varies

In the late 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began marketing prescription opioid pain relievers as drugs that were not as addictive as previously thought, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As a result, these drugs, which had formerly been prescribed only to treat acute pain, became the prescription of choice to treat chronic, long-term pain.

Les McColgin, a liaison for the Houston Recovery Center who was addicted to opioids and used them for 35 years on and off, said he witnessed this change firsthand.

“Back in the late ’90s, you had the situation with Purdue Pharma and the new drug oxycontin ... and that whole situation where they were able to coerce the [Food and Drug Administration] into mislabeling the drug so it was presented as nonaddictive,” McColgin said.

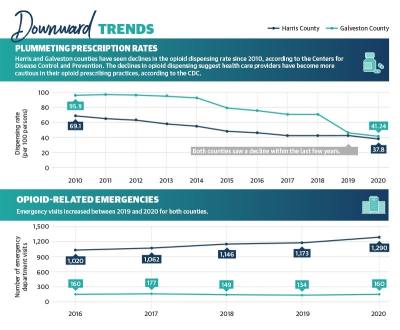

In 2020, a little more than five prescriptions were issued on average for every 15 residents in Harris County in 2020, with a little more than six prescriptions being issued for every 15 residents in Galveston County, based on the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

On the other hand, the dispensing rate declined sharply in Galveston County between 2018 and 2019, after steadily decreasing since 2010, and continued to slightly decrease in 2020. Harris County’s dispensing rate has been steadily declining since 2010. Despite declining dispensing rates countywide and across the state, reported opioid overdose deaths rose 25% from 2019 to 2020 in Texas, according to the NCHS.

According to the CDC, synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, have been one of the major driving forces in the rise of overdose deaths. One of the reasons for this, McColgin said, is fentanyl is unknowingly being put into other drugs, such as cocaine and methamphetamine, and showing up in more overdoses and deaths than it had been previously.

“To be honest with you, I was never scared of anything. It didn’t matter; I wanted it as strong as I could get it. [Fentanyl] scares me,” McColgin said.

Due to his experience, McColgin has brought attention to the use of Narcan, a nasal spray that can be administered during suspected overdoses, to the League City Police Department and similar entities.

Mary Beth Trevino, the Galveston County community coalition coordinator at addiction treatment center Bay Area Council on Drugs and Alcohol, agreed fentanyl is dangerous.

“We have data to support that there has been a significant increase in fentanyl showing up [in Galveston and Harris counties],” she said.

Pandemic effects on treatment

Varisco described several underlying causes of substance use disorders the pandemic has exacerbated, including patient access to treatment, increased financial stresses and isolation. Varisco said he believes the drastic changes to health care for individuals experiencing addiction undid recovery work performed for patients before the pandemic.

According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, which compiles national patient discharges from treatment for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, detoxification discharges decreased from 20% of all discharges to 16% from 2016-19. However, the patient completion rate of detoxification treatment remained stable with fewer than half of patients completing treatment.

“When you have a destabilizing event like a global pandemic, [vulnerabilities in health structures] become more evident,” Varisco said.

With in-person treatment at risk due to the coronavirus, health care centers went remote in 2020. Many centers were limited to offering substance use disorder care through telehealth services as opposed to in-person and personal programs, complicating opioid recovery for patients.

Jimmy White, the executive director of AIM Recovery Center, a Dickinson-based addiction treatment center, said that as a newer center, staff is trying to perfect virtual treatment.

“We want to be able to provide actual, true outpatient-level care, like intense outpatient-level care, virtually,” White said. “One of the dangers of addiction is oftentimes the home is a very unsafe place for them. That’s one of the giant hurdles if we were ever going to try to actually unveil true inpatient virtual [care] is how do we deal with the safety or lack of safety of the home?”

White admits that implementing virtual care would definitely be tricky, and despite not having any major ideas on how to proceed in it, he does believe that it can be done in the near future.

Despite being less effective, telehealth did allow some smaller clinics and private practices to expand their coverage areas. Lori Fiester, the clinical director at the Houston-based nonprofit Council on Recovery, said telehealth allowed patients without transportation access or those who are immunocompromised to receive care they otherwise could not.

“We’ve had people across the state in our groups, including in the Austin area, which was really helpful for our groups to stay vital,” Fiester said.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Varisco said there was some confusion about what treatments were acceptable. A 2020 memo from Phil Wilson, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission executive commissioner, said buprenorphine could be prescribed virtually, but methadone required a face-to-face evaluation.

According to SAMHSA, buprenorphine and methadone are FDA-approved drugs used in combination with counseling to treat opioid use disorders.

“I don’t know if [the policy] was well understood by providers, and that led to lapses in our treatment,” Varisco said.

Some barriers for treatment go beyond drug-related issues. Varisco and Pearson both agreed the lack of accessible public transportation in Texas increased difficulty for lower-income patients.

“If you’re prescribed for buprenorphine or methadone, or whatever, you have to take a bus across the city [of Houston] to get the prescription,” Varisco said. “Proximity to care is just not there.”

Government solutions

State and county entities are working to address the opioid epidemic and the effects the pandemic had on recovery through local funding, law enforcement resources and increased education surrounding opioid misuse.

Many officials agree the use of Narcan is something that should be encouraged and used by emergency agencies.

“We do train lots of different people how to recognize an opioid overdose,” Trevino said. “We’re training people to use Narcan, and we’re supplying them with Narcan. We’re big, big advocates of Narcan.”

Statewide, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton announced Feb. 16 that the state had secured a $1.17 billion settlement with three major pharmaceutical companies: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson and Cardinal. According to the attorney general, Texas has secured $1.89 billion to date from opioid settlements.

Paxton’s office has also reached out to local governments, encouraging them to sign onto existing settlements to receive funds. According to the attorney general’s website, 482 Texas municipalities signed onto two settlements with Janssen—owned by Johnson & Johnson—and with AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson.

According to documents from the attorney general’s office, the cities of Houston and League City, as well as Harris and Galveston counties, are all expected to receive settlement funding. Houston is set to receive $7 million; League City will receive $302,418; Harris County will receive almost $15 million; and Galveston County will receive $1.1 million.

A list of funding uses provided by the attorney general’s office includes community drug disposal programs, training for first responders and youth-focused programs that discourage or prevent misuse.

McColgin encouraged people to disregard any previous notions they might have about opioids.

“This idea that it’s only heroin addicts and hardcore drug addicts that are overdosing on this stuff has to be completely eliminated, or else we miss the most vulnerable people,” he said.