“She’s like, ‘Ms. Bell, what are we supposed to do?’ And I don’t have an answer for that,” said Bell, who was the Democratic nominee for the U.S. District 14 representative seat in November. “We’re going backwards in the areas of being able to take care of our families and ... ourselves.”

Bell is among several local community leaders of color who said Black and Hispanic people in Houston have been disproportionately affected as the COVID-19 pandemic stretches on.

A lack of access to proper resources, particularly health care and monetary assistance, has led to widespread negative effects on these populations’ physical, emotional and financial health.

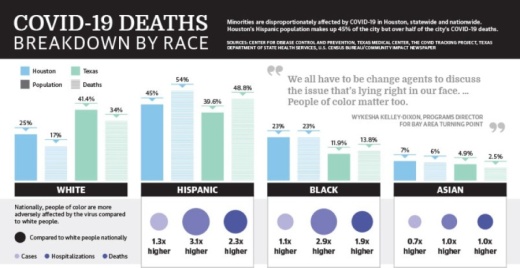

While COVID-19 has affected everyone, people of color—particularly Hispanics—have had the majority of cases, hospitalizations and deaths. In Houston and Texas, Hispanics lead in COVID-19-related deaths, according to the Texas Medical Center and Texas Department of State Health Services. Black people lead the nation in COVID-19 deaths, according to The COVID Tracking Project.

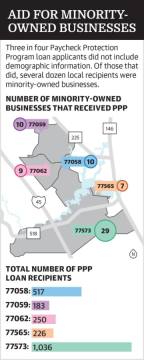

Additionally, there are disparities in economic relief. Of the more than 2,200 businesses in Bay Area cities that received Paycheck Protection Program loans through August, fewer than 70 were minority-owned, per the U.S. Treasury Department.

The momentum gained by the Black middle class in the last 10 years has been slowed by COVID-19, even in the Houston area, where Black business owners can generally prosper, said Farrah Gafford Cambrice, associate professor of sociology at Prairie View A&M University.

“It’s definitely going to come with some struggles for some time to come in terms of health care, economic opportunities and jobs,” Cambrice said. “The pandemic has just kind of layered on inequality after inequity after inequality for people of color.”

Health care inequities

Racism and structural inequality create environments where Black people are exposed to more illnesses, Cambrice said. As of February, Black and Hispanic Americans are 2.9 and 3.1 times more likely, respectively, to be hospitalized with COVID-19 compared to white people, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On an A-F grading scale, The American Lung Association ranks both Harris and Galveston counties at an F for air quality. For people of color in southeast Houston communities, including Texas City, living in environments with toxic air quality leaves them at higher risk for asthma, which is a leading cause of COVID-19 infection in some places, Bell said.

Cambrice and Elizabeth Perez, director of the Office of Communications, Education and Engagement at Harris County Public Health, emphasized many workers of color are in lower-wage essential-worker jobs, often without a path to making more money or access to proper health insurance.

Workers in grocery stores, construction and health care, for example, are often largely Hispanic, Perez said. Black middle-class families, in which the breadwinners may be working in lower-paying industries such as fast food or hospitality, often walk on a financial tightrope, Cambrice said.

The Hispanic community is one of the least insured populations, leading to more chronic conditions, Perez said. Data from nonprofit Greater Houston Community Foundation shows in 2017, the uninsured rate for Harris County’s Black adults was 22.6%—twice as high as that of the white uninsured population, 11.1%. The disparity was even greater for Hispanics in Harris County with 43.9% of the population uninsured.

“It’s this chronic underbelly of health disparities that exist in the community,” Perez said. “It’s a very hard decision ... between if you are going to seek health care or put food on the table.”

Research has shown particularly in the last five years that Black families are turning to multigenerational housing—extended families living under one roof—as a way to recover financially and receive support from relatives, Cambrice said. The same is true for Hispanic families, Perez said, who tend to have a tight familial culture.

While families do receive those benefits while cohabitating, it complicates self-isolation, quarantining or social distancing practices in many cases, said Cambrice, Perez and Wykesha Kelley-Dixon, director of programs at Bay Area Turning Point.

Emotional toll

As Black and Hispanic families deal with the stressors brought on by a lack of proper medical access, many are experiencing declines in mental health as the stability of their lives is called into question.

In the Bay Area, resource disparities that were present before the pandemic became even greater as it unfolded and “left a lot of communities of color feeling hopeless, [like there] was nowhere to turn,” Kelley-Dixon said.

Statistics kept by the nonprofit show a lack of resources to deal with mental health and substance use in local communities of color, Kelley-Dixon said, which is further exacerbated as people are told to socially distance, keeping them isolated from others. Many people of color therefore cannot gain the perspective that the pandemic will one day be behind them, she added.

“We all have to be change agents to discuss the issue that’s lying right in our face,” Kelley-Dixon said, adding the disparities in health care are profound. “People of color matter too.”

Cambrice said she is concerned particularly about Black women, who are often seen as the center of their communities. They have lost access to activities such as going to church, connecting with friends on weekend getaways or attending other community events, so their support system is diminished, she said.

For Tarsha Adams, owner of Feta Candles and Massage in Webster, the pandemic has eliminated time spent at gatherings in family members’ homes. Her family instead keeps in touch through a Facebook Messenger group chat, where she said new messages and calls come in all day and every day.

“Limiting some of the gatherings that we go to has been a bit hard,” she said.

In Harris County, Perez and her community outreach teams are working to build trust and assuage anxieties among Hispanic families. Aside from answering phones at call centers, staffers have given out more than 100,000 care kits letting people know where to qualify for assistance, Perez said.

Still, Kelley-Dixon said public health and nonprofit organizations face an uphill battle trying to assist these struggling communities.

“Nobody expected for this to go on as long as it has or make the impact that it has, especially for communities of color,” she said of the pandemic.

Job prospects uncertain

As more people of color reach out to Bay Area Turning Point for services, many need help securing jobs—but jobs are hard to come by when many do not have the proper education, Kelley-Dixon said.

The nonprofit offers job coaching classes and helps connect people with employment opportunities while also trying to keep clientele from feeling overwhelmed, she said. However, lack of a four-year college degree often shuts people out of better-paying jobs with remote work ability, and restaurant and retail openings have been scarce, she added.

Improving educational opportunities and quality of life for communities of color will be integral to their success moving forward, Bell said. Receiving a post-secondary education is one of the best paths to upward mobility, Cambrice said, but the effects of the pandemic on families of color will impede minority students’ ability to further their studies. The effects on generational wealth could be long-lasting.

Adrienne Taylor provides financial counseling to businesses through her League City-based company Tailored WealthSaver. Black business owners are struggling, she said; she knows of two locally that have closed in the last year, and said one client came to her on the brink of suicide because the inability to provide was a burden on the client’s family.

Because of a lack of pre-existing wealth, many families of color had no way to build an emergency fund for unexpected circumstances like the pandemic, she said. She has provided as much financial literacy training as she can for free in the last year, knowing that Black entrepreneurs are less likely to have this wealth or a relationship with a bank.

However, Taylor has also seen increasing amounts of resilience from Black entrepreneurs as communities come together to support their businesses. Sheldon Isaac, owner of Jaquay’s Chicken and Waffles in Dickinson, said while he is more concerned with product quality than race of customers, recent community focus on Black-owned establishments has helped the restaurant.

“That push [to buy Black] really allowed us to stay, and I got a lot of new customers from that,” he said.