The same route taken by formerly enslaved people and others leaving Galveston is being studied for designation as a national historic trail, known as the Emancipation Trail, after Congress in 2020 approved an amendment to the National Trails System Act allowing for new designation.

Juneteenth, celebrated each year on June 19, honors the day Union Gen. Gordon Granger came to Galveston to announce the liberation of enslaved people in Texas. This occurred in June 1865, more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation became official in 1863. The Emancipation Trail would honor the history behind the day, the ensuing migrations of newly freed Texans and the building of Black communities in areas like Houston’s Fourth Ward.

U.S. Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, worked with U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Houston, on the legislation that paved the way for the study. Cornyn hopes the significance of the trail will one day live beyond history books, he said at an event celebrating the passage of the legislation in March 2020.

“The significance of this path extends far beyond the elation [formerly enslaved people] felt on that day,” he said of Juneteenth and the trail. “It paints a picture of early beginnings of Houston, a strong African-American community that is, of course, now such an important part of ... this incredibly diverse and beautiful city, and it also represents the eternal struggle for equal rights, which continues to this day.”

Emancipation Trail planning

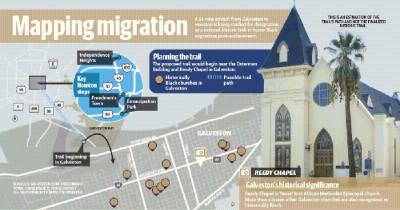

The Emancipation Trail would begin near the Osterman Building and Reedy Chapel in Galveston, go along Hwy. 3 and I-45 to Freedman’s Town, then go to Independence Heights and end in Houston’s Emancipation Park. It would be one of just two trails in the country commemorating the migrations of formerly enslaved people, with the other being from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Emancipation Park was established when, after Granger’s announcement, Black people across Texas collected money to buy property dedicated to Juneteenth celebrations. A formerly enslaved Baptist minister led efforts to do so in Houston, purchasing the park’s land in 1872 for $1,000 as home for his community’s celebration and naming it in honor of their freedom, according to the Houston Parks & Recreation Department website.

There are 19 national historic trails already established in the United States, all following past routes of exploration, migration, struggle, trade and military action. Two national historic trails crossing through Texas honor its journey to statehood and major cultural exchanges.

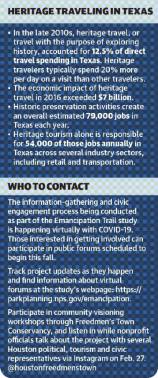

A House of Representatives report notes the cost of the Emancipation Trail would not exceed $500,000 over the course of three years, which is the approximate timeline given for the study’s completion. Having the Emancipation Trail recognized would add economic value for cities and towns along its path, providing a new historic site for visitors, said Tommie Boudreaux, the African-American Committee chair of the Galveston Historical Foundation.

“From what I’ve read about [the other trail], it has really improved [things] economically in that area,” Boudreaux said.

While NPS officials do not have data specifying the economic impact of national historic trails, Texas Historical Commission data on the statewide Texas Heritage Trails Program shows the tourism impact of heritage travel continues to grow—especially since heritage travelers typically spend more each day than other travelers. More than 10% of all tourism in the Lone Star State can be attributed to heritage travel, or travel with the primary purpose of exploring a place’s history and roots.

The NPS began its civic engagement and information gathering, the first of eight steps in the process, in October, said Lilis Urban, the chief of planning for the NPS’ National Trails Office, in an email. For Congress to designate the trail after the study is completed, the study must result in a positive finding for designation based on specific criteria, Urban said.

The criteria involve the trail’s historical significance as a result of its use—although the trail does not need to follow the historic route exactly if logistical issues arise—as well as the trail’s national significance based on its use having “a far-reaching effect on broad patterns of American culture.” There also must be significant potential for public recreational or historical interest, based specifically on historic interpretation and appreciation.

Bringing history to life

The study’s team is conducting preliminary historical research and route assessments as well as building the contact list for the project, Urban wrote. After gathering input and hearing from the public, the NPS will begin assessing criteria and assembling preliminary findings.

The NPS anticipates holding virtual public meetings in the fall; shortly before the meetings begin, a series of outreach and engagement questions will be posted on the project website. The public can submit responses to questions, as well as any additional comments, online or by mail.

Public input for the study is critical, Urban wrote, including insights about the precise location of the migration route under study, historic sites and stories connected to the route, and whether people would like to see the trail designated. Public perspectives are incorporated into the feasibility study document, which is sent to Congress as the last of the eight steps.

In the Fourth Ward, the nonprofit Freedmen’s Town Conservancy is pioneering efforts to mobilize local Black families and gather their stories and artifacts. As this information is compiled, valuable items are appearing out of nowhere in places such as garages, Executive Director Zion Escobar said.

However, the first challenge faced by those involved in information gathering is making people aware of its importance.

“You’re really trying to get past the big inertia of people hoarding content or even understanding that they actually have something of value,” she said. “What we’re doing in the community is we’re carrying on that message at a hyperlocal level.”

Some individuals and families with historically significant items may be called on to help with the informational resources available about the trail if it is designated. Escobar said the nonprofit will work with these people to prepare them for assisting the NPS and engaging in the process.

Details regarding educational programming, interpretive signage and the location of historic sites, including places where the public could visit, connect and understand the route, would be assessed and fleshed out in a comprehensive management plan after Congress designates the route as a new national historic trail, Urban said. This process would include heavy input from city governments, nonprofits and community leaders.

A liaison with one of Jackson Lee’s advisory groups has already reached out to the nonprofit about the collection of historical information, Escobar said. She encouraged residents to keep up with the nonprofit’s website and social media for community visioning workshops and other ways to get involved with the trail study.

“There’s always these stories within stories that we’re now aware of,” she said.

Juneteenth history

June 19 became a state holiday starting in 1980 after a House bill passed in the 66th Legislature declaring it Emancipation Day in Texas. More than 110 years prior, the day marked a new era for Black communities, spurring their eventual migration to Houston along what could become the Emancipation Trail.

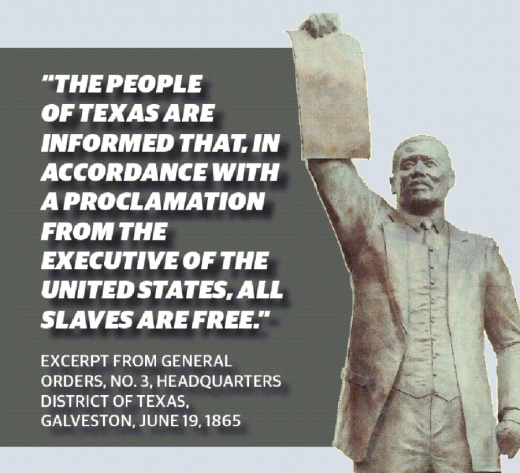

When Granger arrived in Galveston, he issued five orders to its citizens, said Brett Derbes, the director of research at the Texas State Historical Association. The third of the five mentions the abolition of slavery and is “very forward, very clear” from even the first sentence, Derbes said.

“It’s really enormous,” he said of the radical statewide changes that took place from that day on in Texas. “Just the sheer amount of change that occurred ... just changed the entire country in so many ways, and then this, this event in Texas—it’s taking off Reconstruction in Texas.”

The traveling of formerly enslaved people from Galveston to Houston shows they had the necessary skills to live their desired lives, Boudreaux said.

“Houston was a larger city, and they probably had more opportunities to get things done,” she said. “They demonstrated that they could be on their own.”

A 9-foot-tall statue of Granger is visible when driving along Broadway Avenue J, one of the city’s busiest streets, in the courtyard of the historic 1859 Ashton Villa event venue. The statue of Granger was brought to Galveston in the early 2000s, according to the Galveston Historical Foundation.