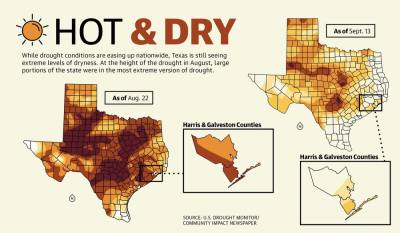

Due to a lack of rain and persistently high temperatures, Harris and Galveston counties were in a severe or extreme drought in mid-June through August, according to standards set by the U.S. Drought Monitor. As of Sept. 15, area drought conditions were moderate at worst, but at its apex, the drought affected area cities, some of which had to enact drought contingency plans to conserve water.

“This drought is extreme,” Jimmy Fowler, meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Houston/Galveston office, said at the height of the drought. “It’s pretty dry.”

While August rains have brought relief, future precipitation could bring another problem, such as floods, which tend to be worse after a drought, said John Nielsen-Gammon, Texas climatologist with Texas A&M University.

Other concerns include droughts and high temperatures possibly becoming more common or dry conditions returning for the remainder of the year.

“Climate change may be making the difference between 101 and 103 [degrees] on a particular day,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

Double whammy

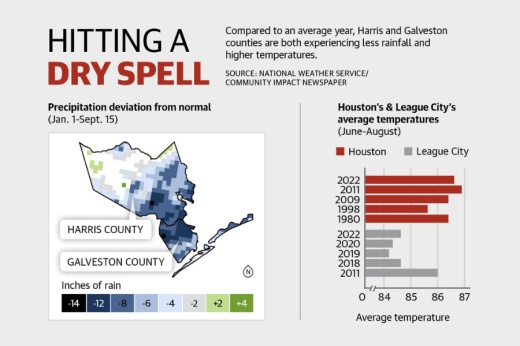

Galveston County entered extreme drought, the second-highest of the Drought Monitor’s five drought tiers, on June 14. Harris County has varied between severe and extreme drought, according to Drought Monitor data.

As of mid-September, Harris County’s drought was mostly gone. Most of Galveston County remained in moderate drought.

Contributing to the drought are the weather patterns seen in the Pacific Ocean, Fowler said.

When the ocean’s surface water temperatures are warmer, it is considered in El Niño, and Texas is more likely to get rain. When the waters are cool, it is considered in La Niña, resulting in drier conditions.

The ocean has been in La Niña for three years, Fowler said.

As of Sept. 15, most of Harris and Galveston counties had seen up to 12 fewer inches of rain than normal since Jan. 1. On top of that, the Greater Houston area experienced one of its hottest summers on record, Fowler said.

June through August was the second-hottest three-month period for League City since at least 1997—tying with 2018 and coming second only to 2011, the last major drought year on record—at an average of 84.6 degrees, according to National Weather Service data.

The records are similar for Houston. June through August was the second-hottest period since 1889 at an average of 86.6 degrees. June through August 2011 ranked first at 87.9 degrees.

“Just the fact that it’s been so warm has really fast-forwarded the drought process,” Fowler said.

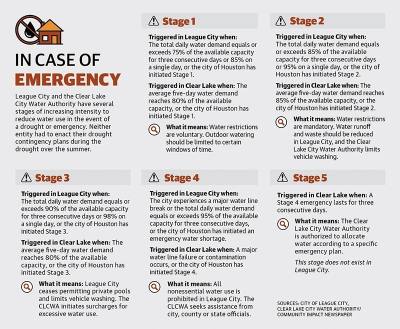

Contingency plans

Houston, Pearland and Manvel are some of the nearby cities that activated at least the voluntary stages of their state-mandated drought contingency plans, which aim to limit water use during emergencies.

However, due to water conservation and other efforts, Clear Lake, residents of which get their water from the Clear Lake City Water Authority, and League City did not have to activate their plans.

Jody Hooks, the public works director of League City, said a combination of investment in water infrastructure and working with homeowners associations and residents to promote water conservation allowed the city to avoid enacting its drought contingency plan.

Prior to 2011, about 75% of the city’s leaks came from old water lines, which are most vulnerable to breaking during droughts. The city’s water line replacement program, which began around 2013 and has cost the city about $2 million annually, has made the system more robust, Hooks said.

Additionally, the city has been pushing the message of water conservation since the 2011 drought, and HOAs and residents are listening and adapting, Hooks said.

“I think water conservation culture today versus 2011 is much stronger,” Hooks said.

CLCWA board President John Branch echoed Hooks. While Houston had to enact its plan, the CLCWA did not, in part due to water conservation efforts from residents and the fact that new houses in the area have low-flush toilets and other water-saving infrastructure.

“We never even got close to what our capacity is for our system,” he said.

One factor that can contribute to whether a city activates its drought contingency plan is ground cracking. The more extreme a drought, the more earth retracts and shifts, which can break water mains, according to officials from various cities.

During a normal week, the CLCWA might see three water line breaks a week. During the drought, it got up to three a day, resulting in the CLCWA spending about $350,000 more than normal on repairs, Branch said.

Ending the drought

In mid-August, the southeast Houston area started seeing more heavy rain, which began to push the area out of drought.

For the rest of 2022, the outlook calls for abnormally high temperatures and dryness to continue, Nielsen-Gammon said. October tends to be a wetter month, historically, which could bring more relief, though he said the odds favor dry conditions, he said.

It is possible a single heavy rainfall could bring the area out of a drought, but that would likely result in flooding due to the fact that dry earth absorbs water slower than moist earth.

The ideal way to get out of a drought is weeks of above-average rainfall to not only meet norms, but also exceed them to make up for the months of lackluster precipitation, and that is what has happened. Galveston County received 3.92 inches more rain than normal Aug. 16 through Sept. 13, Fowler said.

“We’re still slightly on the drier side, ... but we’re no longer in the extreme impacts from the drought,” he said.

The Bay Area has not seen much flooding due to sudden rain. League City has seen minimal street flooding but has been lucky, Hooks said.

“From a utility standpoint, weather’s everything,” he said. “We could roll right back into a dry cycle.”

This winter is expected to be warmer and dryer than normal, so it is possible drought conditions could worsen a bit, Fowler said.

Future concerns

From a temperature standpoint, meteorologists have seen an increase over the past few decades, particularly in overnight temperatures. It no longer gets nearly as cool overnight, which affects droughts, Fowler said.

Due to regional population growth, climate predictions and rain variability, the future drought in Texas may actually be a megadrought, which lasts decades, Nielsen-Gammon said.

A megadrought is caused by climate cycles and change, which Nielsen-Gammon said will cause higher temperatures that diminish rainfall. Texas has historically had unpredictable rainfall patterns, making it difficult to predict droughts, Nielsen-Gammon said.

“Texas is quite variable from ... year to year,” he said. “We’ve had some decades with 50% more rainfall than other decades, for example.”

Shawn Arrajj and Grace Dickens contributed to this report.