The overall health of the industry has fluctuated in the last decade, experts involved with commercial harvesting and habitat restoration said. With any of the world’s oyster populations, human-made effects have an impact on the industry and the ecosystem, said Raz Halili, the vice president of Dickinson-based oyster distributor Prestige Oysters. In the last 10 years, hurricanes and oil spills majorly affected the Bay Area’s oyster production, he said.

“Mother Nature plays a very big part,” Halili said.

The 2020-21 Texas commercial and recreational oyster season opened Nov. 1 and lasts through April 30. While the calcium content, thickness and density of a shell can change, the oyster species is the same throughout the bay, Halili said.

“Galveston Bay is one of the largest oyster-producing areas in the country,” he said. “It’s something [for] ... people to understand and take pride in.”

Striving for sustainability

Haille Leija, the habitat restoration manager at the conservation nonprofit Galveston Bay Foundation, said 2017—when Harvey struck—was supposed to be an “amazing year” for oysters, but the population suffered when the hurricane flooded the bay with freshwater.

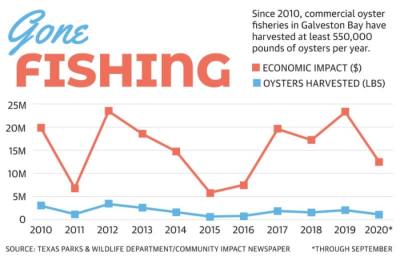

The San Leon region, she said, has still not recovered, but the Galveston Bay area’s oyster population is still active. Between 2010-20, an average of 1.8 million pounds of oysters was collected in the bay annually, according to Texas Parks & Wildlife Department data.

Overall, oysters are resilient but still are affected by day-to-day events. Oysters are triggered to spawn by temperature and salinity. If the water is too fresh, such as after Harvey, the shells may remain closed to maintain their internal balance, but oysters cannot survive that way for long. Droughts can result in high salinity, which happened from 2010-14, Leija said.

Smaller-scale efforts to preserve the area’s oyster population are time consuming and not always easy, but they are still happening, Galveston Bay Foundation officials said. Those efforts are being executed by individual communities through the foundation’s oyster gardening program.

Each spring, the foundation works with interested bayfront property owners, teaching them how to create and maintain the gardens with recycled shells.

In May and June, each volunteer suspends their oyster gardens in the water below their dock or pier then monitors the gardens for fouling, predators and the growth of baby oysters—known as “spat”—on the shells. By fall, those spat will grow up to 1 inch or more, at which point they are ready to be transplanted onto nearby restoration reefs and continue their water filtration work.

Oyster gardeners in Tiki Island were seeing growth on shells in early November, according to a local Facebook group.

Bay Area program participants have built a “culture of pride” around their work with the gardens, said Michael Niebuhr, the Galveston Bay Foundation’s habitat restoration coordinator. They often refer to themselves as “oyster foster parents.”

“They take it and run with it,” he said.

Maureen Nolan-Wilde, gardening leader in Tiki Island, said the program has continually grown as people of all ages take interest.

“It’s very community focused, and ... people get hands-on experience bringing nature back to areas that are in danger,” she said. “It resonates with a lot of people, and it’s easy, fun and educational.”

Contemporary changes

The state’s changing role in oyster management has resulted in growth for the area’s oyster industry over the last three years, Halili said. From 2007-17, about $10 million was funneled into oyster reef restoration in Galveston Bay, a majority of which was from federal funding sources, according to TPWD officials.

Some of the state’s management practices have included closing parts of Galveston Bay off to oyster fishermen. This means the fishing boats may have to travel farther to get to oysters, and small businesses cannot afford to do that, Niebuhr said.

“I think the industry is feeling that,” he said.

After a two-year certification process, which included a 10-month assessment by a third party, Prestige Oysters in 2020 became the first fishery in the Americas to receive a Marine Stewardship Council certification for its work in sustainable practices. The council has recognized sustainable fishing practices at more than 300 fisheries in more than 34 countries, and major grocery stores source their products from MSC-certified fisheries.

Prestige was measured based on the sustainability of its fish stocks, environmental impact and a responsive management system. The company had already been employing a majority of the practices that were required for certification, Halili said.

“We were already doing a lot of those things, and so I felt it was possible,” he said. “It was just pulling in the right information to show the assessors what we were doing.”

The Galveston Bay Foundation partners with commercial fisheries when possible to build small, protected reefs, Leija said. The projects are built in areas that are off limits to harvest, so they will not be touched, she added.

“What we’re trying to do is create kind of a sanctuary,” she said.

COVID-19 impact

The effects of the coronavirus pandemic are being felt in the commercial oyster industry. Some fisheries will qualify for relief through the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act if they suffer more than a 35% loss of revenue over the previous five-year average, said Darin Topping, trip tickets coordinator with TPWD.

Sales at Prestige were down as much as 90% during the first lockdown in the spring, from late March through April, Halili said. The company kept the boats working and froze as many oysters as possible to sell later.

While the market picked back up during May, Halili said it took a dive once more in late June and early July. Summertime oysters eventually became too large for the market, and they also do not freeze well, Halili said—leaving oyster fishermen at Prestige without many other options.

“We’re kind of just in limbo like everybody else,” Halili said. “Lost sales are lost sales, whichever way you look at it.”

Sales are down 15% to 20% year over year, he said. Although Prestige moved a “steady amount” of oysters throughout the summer, the wintertime will likely be challenging, he added.

“The market right now ... is definitely not taking off like it normally does,” Halili said, adding tensions around the election season are also contributing. “The market’s reacting to [current events].”

Giving back

Shell recycling, oyster habitat preservation and restoration are all commonplace throughout the Bay Area with large-scale efforts from fisheries, oyster gardening in bayfront communities and shell-recycling programs in local seafood restaurants.

Oyster reefs have been disappearing since the early 1900s due to mass dredging, Halili said. At Prestige, 100% of the shells the fishery accumulates when shucking oyster meat are recycled and returned, along with rock, to the gulf.

To date, 400 million pounds of rock have been replaced, Halili said. This allows oysters to form new habitats and regrow into the previously occupied shells. Up to 20 oysters can attach to a single shell, Galveston Bay officials said.

“It’s a year-round thing; our captains are out there daily on the water,” he said about the shell and rock deposition.

Captains are constantly developing and improving their methods for this process, particularly because it has to be done before oysters spawn—which happens in the early spring and fall—to get the best effect and not have algae grow over the rocks, Halili added.

Restaurants can choose to partner with the Galveston Bay Foundation to recycle their oyster shells on a smaller scale compared to Prestige’s commercial practices. The recycling program started in 2011 and has since grown to include nine Bay Area eateries. In 2018, the foundation returned 200 tons of shells to the bay and restored a quarter-acre of reef, officials said.

Rey Montemayor, who manages Tookie’s Seafood Restaurant in Seabrook, said participating in the program is relatively simple from the restaurant’s perspective. Oyster shells are put in bins provided by the Galveston Bay Foundation, and someone from the foundation comes to clean them and return them to the bay. The program was put on hold from late March to early May as restaurants closed during shutdowns, Leija said, but it quickly resumed.

“It’s a pretty simple process,” Montemayor said. “We’re basically just shucking the oysters and then putting them in their bins, and then they just take care of the rest of it.”