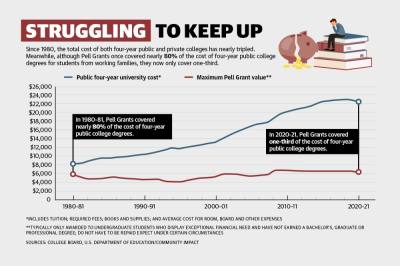

Adjusted for inflation, the average annual cost of attending a four-year college full time—including tuition, fees, room and board—in the U.S. has risen from $10,231 in 1980 to $28,775 in the 2019-20 school year, a roughly 180% increase, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“We’ve been telling everybody for decades, ‘You have to go to college,’ so the demand has shifted out like crazy, and lots of colleges aren’t functionally much bigger than they used to be, so each spot is more expensive,” said Dietrich Vollrath, a professor and chair of the Department of Economics at the University of Houston.

Federal Reserve System data shows more than 45 million borrowers nationwide have contributed to a cumulative student loan debt of roughly $1.75 trillion with more than $1.6 trillion of those loans issued by the federal government. In Texas, 52% of college graduates in the 2019-20 school year had taken on student loan debt with an average debt of $26,273, according to The Institute for College Access & Success.

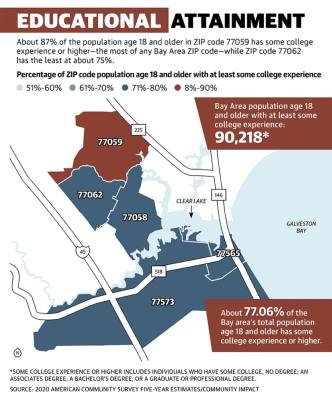

In the five ZIP codes that make up the Bay Area, data shows over 90,200 people age 18 and older have some college experience or higher, or roughly 77% of the local population age 18 and older, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

Locally, the cost of tuition—not including additional fees—for 24 hours at San Jacinto College, which has a campus along Spencer Highway in Pasadena, has increased by roughly 42% between the 2012-13 and 2022-23 school years, while the average annual cost of tuition at the University of Houston-Clear Lake has increased by over 47% within the same time frame, according to data from the colleges.

In hopes of providing relief, President Joe Biden announced Aug. 24 he would issue an executive order that would have enabled nearly 43 million Americans to have up to $20,000 in federal student loans forgiven. On Nov. 10, a Texas judge blocked the program, and the Biden administration stopped accepting applications for forgiveness.

While the plan was hailed by borrowers, experts said they feared the loan forgiveness would lead only to further tuition inflation. Betsy Mayotte, president of The Institute of Student Loan Advisors, said while she supports the initiative, she believes it fails to address the root cause of the problem.

“Everybody talks about the student loan crisis, and it exists, but it’s a symptom—not the problem,” Mayotte said. “The problem is the cost of higher education, and this plan does nothing to address that.”

Costly tuition

Vollrath said inflation plays a role in the rising cost of attending college, but he also noted two additional factors that have led to steadily rising tuition rates.

According to Vollrath, rich economies such as the U.S. tend to see faster rates of inflation for services such as education and health care when compared to manufactured goods because the cost of producing those goods diminishes over time.

Additionally, there has been a decrease in financial support from state governments. Between 2008-18, state spending for higher education in Texas dropped from $9,256 per student to $7,107—a 23.3% decrease, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

“We’re getting around half the money we thought we might have been getting 20-30 years ago, and you have to account for it, so that ends up getting unloaded on the students usually,” Vollrath said.

During that same time frame, the average cost of tuition at four-year public colleges in Texas increased by $2,302, or 30.4%, CBPP data shows.

“State schools are really like the anchor price of colleges and universities, so if your anchor-price product is going up, it means that the private, more elite schools can raise their prices and still pass the laugh test,” Mayotte said. “But if you lower the cost of your state institutions, that hypothetically would force these private universities to lower [their cost] just to be competitive.”

However, Vollrath said he did not think the blame should be directed solely at declining state contributions to higher education.

“Why are universities paying for things that seem to drive up tuition that don’t seem to contribute towards the baseline of educating students?” he said.

Plan basics

As outlined in an Aug. 24 news release from the White House, Biden’s three-part plan aimed to provide up to $20,000 in debt cancellation to Pell Grant recipients with loans held by the U.S. Department of Education and up to $10,000 in debt cancellation to non-Pell Grant recipients.

The Biden administration began accepting applications for loan relief Oct. 17. After the program was blocked, the White House halted accepting applications but said in a statement they have appealed the decision.

Individuals would have been eligible for this relief if their income is less than $125,000 or $250,000 for married couples. Current students with loans would also have been eligible for debt relief; however, borrowers who are dependents would have been eligible based on their parents’ income.

Additionally, the White House announced Aug. 24 the pause on federal student loan repayments would be extended through Dec. 31 and that borrowers should expect to resume payments in January. Despite the loan relief program block, the repayment pause is still in effect.

The Department of Education estimated roughly 43 million borrowers would have qualified for relief, including 27 million borrowers eligible to receive up to $20,000 in •debt cancellation.

“People that owe [$10,000] or less or [$20,000] or less tend to be the ones that struggle the most,” Mayotte said. “The reason their balance is so low to begin with is because of one of two things: Either they’ve been paying forever, or ... they have debt and no degree.”

Mayotte believes this is not the end of Biden’s initiative.

“I do still think the forgiveness will go through,” she said. “All borrowers can do right now is sit tight. If payments resume in January and this isn’t settled yet, they should discuss options such as forbearance or income-driven plans with their loans servicers.”

Local perspective

Across San Jacinto College, the cost per credit hour this fall is $78 for in-district students. These rates have been the same since at least the 2019-20 school year, said Teri Zamora, SJC vice chancellor of fiscal affairs.

According to data from SJC and UHCL, SJC, a two-year college, is cheaper than UHCL, a four-year college, where the preliminary cost per credit hour is $251 for 2022-23—the same as last year.

Less than 3% of SJC students borrow loans, and that is at an average of $3,062. At UHCL, 28% of students borrow, and that is at an average of $9,632, according to data from both colleges.

“Students can remain at home with their families in east Harris County while attending San Jac and save money on rent and utilities and graduate with little to no college debt,” Zamora said.

Still, UHCL prides itself on its cost.

“UHCL is one of the most affordable four-year universities in Texas,” said Kara Hadley-Shakya, UHCL interim vice president for strategic enrollment management. “Our focus is to keep education affordable.”

Mark Denney, UHCL vice president for administration and finance, agreed.

“UHCL offers a focused path to complete your full bachelor’s education in four years at a relatively low cost, where many community college students can transfer and still need to spend more than an additional two years at UHCL, making the total cost much closer if not more than attending UHCL from the start,” Denney said.

SJC officials said one of the college’s goals is a low cost of entry for students.

“We work to remove any barriers our students may encounter in their pursuit of their educational goals, and that includes keeping the cost of obtaining that goal to a minimum,” Zamora said.

Saab Sahi contributed to this report.