The district’s 2020-25 strategic plan, approved by the board of trustees in May 2020, includes a specific result statement about “increased inclusivity for all.” Superintendent targets were approved by the board the following September, and those targets included an equity audit.

The equity audit was commissioned by former Superintendent Greg Smith in December and concluded in April. The findings from the audit, which was conducted by Curriculum Management Solutions Inc., were presented to the board of trustees Aug. 23.

CMSi concluded there are unclear definitions around equity in CCISD; economic need has an influence on end-of-year exam performance; and the diversity of CCISD’s student population is not being represented in staff, among other findings.

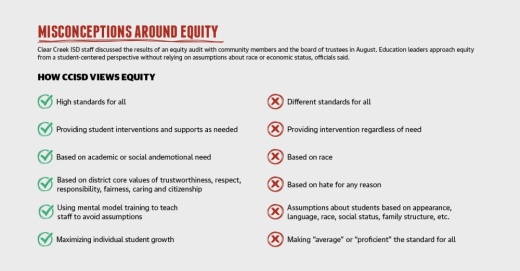

These results are just one piece of the puzzle, district officials emphasized, when it comes to how they approach serving students’ academic, social and emotional needs. Providing equitable education in CCISD means extending support and interventions as needed, rather than instituting a practice regardless of need, Williams said.

“The audit really hasn’t shifted our work or changed the nature of our work,” he said. “It’s all about maximizing individual student growth instead of trying to get everyone to ‘average’ or ‘proficient.’”

Parents and community members said during July and August board meetings they were concerned how equity-related initiatives might look on campuses, worrying children or teachers might be singled out or deprioritized based on identity markers. Maximizing individual growth will be done independently of traits such as race and economic status, officials said.

Education equity experts and CCISD officials said schools are meant to be places where the whole child can be educated. With the audit results at their disposal, district leaders said they will look for ways to put continual, widespread focus on social and emotional learning as well as fostering cultures that are centered around success for the individual student.

Audit findings

The audit, which cost the district around $14,000, produced findings split into three categories: vision and expectations, access and equity, and academic achievement.

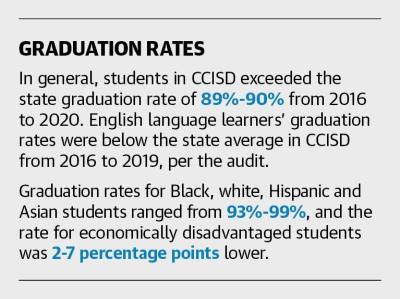

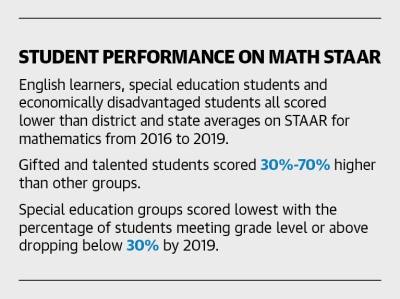

One of the academic achievement subsections found economic disadvantage had an influence on student achievement. Elementary and intermediate schools with the highest percentages of economically disadvantaged students had the lowest reading and math State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness scores in 2019, per the audit.

Another subsection examined disparities in STAAR scores among English learners, special education students and economically disadvantaged students, who, on average, scored below the district and state averages 2016 through 2019, per the audit.

Ashton Millet, who works with advocacy group One Houston to address equity in schools, said underperformance by students of color is often connected to implicit bias. Equity audits serve to illuminate gaps for districts and help them maximize social and emotional learning, or SEL.

“Those are all things that can get overlooked, but if you look at them, academic achievement is going to fall in line,” Millet said.

The audit also found CCISD’s staff was disproportionately white: An average of 77% of staff from 2018 to 2020 were white compared to roughly 46% of students, per audit data. Some schools with the greatest percentage of economic disadvantage had the lowest percentage of teachers with the same ethnicity as the students. By grouping students together based on economic data, the audit overgeneralizes CCISD’s learners, said Robert Bayard, deputy superintendent of curriculum and instruction. Not all students in a certain group will perform at the same level, he said. District leaders may revise an audit recommendation to meet CCISD needs before implementation, or may not act on some recommendations at all, officials said.

Ensuring equity at CCISD also means pushing high-achieving students to supplement classroom learning with new extracurriculars, CCISD board President Jay Cunningham said. The goal is to allow each student to grow at the right pace for them, not the right pace for a peer with a similar ethnic identity or academic proficiency, CCISD leaders said.

“It’s not about just focusing on one category of student, including students that you might group in terms of academic levels,” Williams said. “That can provide comfort to parents who are focused on the success of their specific son or daughter."

Any audit-related recommendations would be brought to the board before implementation, Bayard said. CCISD leaders have not made decisions on the recommendations as of October.

Serving students

The first of the three audit findings indicated CCISD’s policies lack clear definitions and expectations as they pertain to “equal access and comparable learning outcomes for all students”; it is accompanied by a recommendation to adopt a clear vision for equity.

“I don’t want [the word] to distract us from our principles of providing services to our community based on need,” Bayard said regarding his desire to avoid the word “equity.”

CCISD parent Aline Barcelloy expressed concerns at the August board meeting about the messages the audit results might send to children, including her 5-year-old daughter, who is an English language learner. She said she does not want her daughter to think having an immigrant parent or being taught by someone of a different race makes her less capable of learning.

“Is the message that she needs a Brazilian teacher to teach her, or else she won’t be [as] capable of learning as her peers?” Barcelloy asked Aug. 23. CCISD leaders approach equity from a student-centered perspective without relying on assumptions about race or economic status, Cunningham said. Meeting social and emotional needs for students includes providing access to educators that look like them and can understand them, from principals to counselors, he and Millet said.

Emphasizing SEL promotes healthy school cultures that will encourage teacher retention, Millet added.

“That’s impactful for the teachers as well, and it creates an environment that people want to come to,” he said.

CCISD has worked in the last several academic years to add counselor and social worker positions, some in light of COVID-19-related challenges, CCISD Chief Communications Officer Elaina Polsen said.

Cunningham hopes to see consistent district presence at historically Black college and university job recruitment fairs, such as Prairie View A&M University and Texas Southern University. CCISD sent a representative to a PVAMU fair this fall and went to TSU on Oct. 8, Polsen said.

Ongoing evaluations

CCISD is not the only Houston-area district to grapple with equity questions this year, and this is not the first instance of the district commissioning an audit.

Spring ISD officials reviewed in May the results of a similar study, which found an overrepresentation of students of color in SISD’s special education population, which was also identified by CMSi in CCISD’s audit.

Cy-Fair ISD also hired an outside firm to conduct an equity audit this year; officials said results will be made public this fall. Aldine ISD is conducting an equity audit and will be engaging families in focus groups this fall.

Equity audits can help districts identify how unconscious bias might affect student intervention, Millet said.

CCISD conducted another audit three years ago in response to concerns from a specific population. CCISD hired Gibson Consulting Group in 2018 to examine services for its special education population after several parents protested against CCISD, claiming its special education students were mistreated by district staff who were not properly trained.

The group released a report in March 2019, which indicated the district could improve special education-related professional development, data usage and parent-administrator relationships. Of the 25 recommendations outlined in the report, three are in progress as of October, and the other 22 are complete, Bayard said.

Cunningham encouraged the CCISD community to remain open-minded as the district works to best serve the varying needs of its 41,000 students.

“We’re all really in it for the same thing,” Millet said. “We want all of our students to be as successful as they possibly can be.”