The district hired Gibson Consulting Group in August 2018 after several parents raised concerns and protested against CCISD, claiming its special education students are abused by district staff and that staff are not properly trained to best educate their children.

In March 2019, Gibson released its report, which showed the district has many strengths as well as highlighting several areas in need of improvement. These areas include professional development, data usage and parent-adminstrator relationships, among others. The report also compiled and presented similar districts and state and national averages. The audit cost the district $149,500.

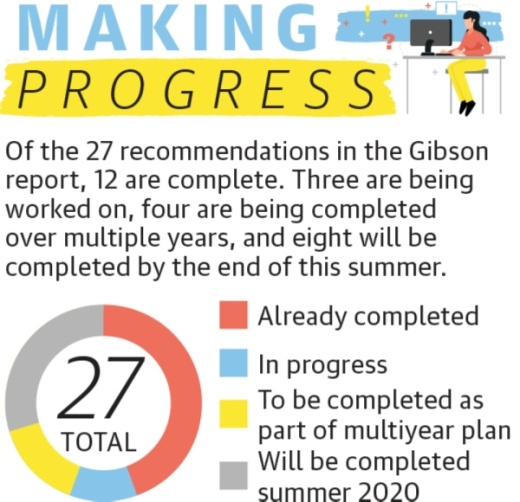

There were a total of 27 recommendations in the report. As of November, 12 have been completed, and plans are in place to complete all remaining recommendations by mid-2022, said Steven Ebell, CCISD deputy superintendent of curriculum and instruction. Three more recommendations are in progress as of press time, CCISD officials said.

The district serves nearly 5,000 special education students and more than 7,000 students in special services overall.

“We can fairly well meet the variety of needs that we have,” Ebell said. “Our focus with this review, really, is just getting better.”

STEPS FORWARD

Parents of some special education students feel there is still a disconnect between what CCISD officials say they are doing in terms of reform and what actually happens.

“They talk the talk and don’t walk the walk,” said Dawn Lynd, a parent of a special-needs student who she said suffered injuries while in CCISD care due to improper seclusion and restraint.

The Gibson report did not address specific, measurable action items the way special education parents asked for, several said. Parents originally requested a full investigation of past alleged infractions, but the audit did not do that.

The audit also did not include children or families who had since left the district due to problems with CCISD’s special education program, which Lynd said means it cannot be truly reflective of the issues at hand.

“It’s all toothless stuff,” special education parent Alice Machin said.

The Gibson report recommended changes related to CCISD’s approaches with students and culture around special education as well as reforms to administrative practices and accountability measures.

Two of the major reforms already completed are the addition of a special education parent resource center and the formation of a districtwide Special Education Parent Advisory Committee.

However, some parents said neither of these allow for accessible, two-way communication between parents and the district.

The center opened in September, and its hours are 9 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Amparo Chacon, whose special-needs son graduated from CCISD in 2015, said more parent trainings are needed at the center at more accessible hours.

“For the most at-need families ... [they] are offering classes during the day when a minimum amount of parents can do it,” she said.

CCISD Chief Communications Officer Elaina Polsen said in an email that she plans to speak with the center’s director about adjusting hours to better accommodate parents.

“We ... certainly can understand how that can be limiting for working families,” she said.

SEPAC comprises one randomly selected parent from each of the district’s 44 campuses serving as advisers to Superintendent Greg Smith and the district’s special education leadership team. The last SEPAC meeting was held in November, but minutes are not available online.

Meetings are held four times a year and are for committee members only. CCISD officials said SEPAC is “one of many opportunities” for parents to interact with district and campus staff.

Since the information from the committee seems to stay between SEPAC members and administrators, the reform is insufficient, said Jane Kline, whose son is a special-needs CCISD senior.

“This is a joke,” she said. “They’re not giving this priority; they’re not giving us attention.”

Contrarily, Marta Brain, one of the parents serving on SEPAC, called the committee “a really great tool for parents.” She said meetings have been positive and productive, with administrators genuinely listening to input from committee members. She recalled a SEPAC parent asking a question at a meeting and said administrators diverted significantly from the agenda to ensure the topic was addressed.

Brain will be on the committee a total of two years, but some parents serve for only one based on the random drawing.

Brain said she has seen follow-through from CCISD with points she previously brought up that are now being executed, including increasing disability education efforts, she said.

“It’s a step in the right direction,” she said.

While the existence of SEPAC is in itself a positive step, Brain said, there is a major need for better communication between special education parents and better communication at a district level, including between SEPAC representatives and other CCISD parents.

This also means making involvement as easy as possible for special education parents, many of whom may not physically be able to attend meetings, with amenities such as livestreaming or video conferences. Better communication between CCISD officials and parents would help resolve a lot of the issues most parents have, she added.

Special education parents face additional unique challenges because of their children’s needs since special-needs students cannot always communicate what happens to them at school, Brain said.

“We’re placing more trust in the district,” she said.

REBUILDING TRUST

Administrators said parent feedback throughout the reform process has been positive, but there is still work to be done.

Ebell encouraged concerned parents of special education students to immediately contact officials at their child’s campus if they feel there are issues. If a parent is not satisfied with the resulting campus investigation, they can work with district-level officials through various avenues, he added.

“It’s very difficult having to walk that path with families when their child ends up in special education, and so, we want to really be aware of those needs,” he said. “We admit that we do make mistakes, but our goal throughout this whole process is to make sure that we’re taking actions in the best interest of the student and the family.”

One of the program’s biggest current challenges is a transition in leadership following the retirement of Cynthia Short, the former executive director of special services, Ebell said. The transition may cause interim delays in the completion of the remaining recommendations. The CCISD board of trustees approved Michele Staley, principal of Clear Brook High School, as her replacement at the board’s Jan. 20 regular meeting.

“When there’s concerns, she is very willing to sit down with parents and hear their concerns and then, take action,” Ebell said. “That was a big attraction for [Smith] recommending her for that position.”

Several parents expressed concern with Staley’s lack of experience in special education. Staley has state certifications in secondary biology and physical education and is a certified principal but does not have any certifications related to special education, according to the Texas Department of Education’s certificate database.

“I have been a leader in public education for the past 21 years for both general education and special services students,” Staley said in an email. “I am thrilled that CCISD is allowing me to broaden my horizons by serving the 7,000-plus special services students in our district and will continue to work for their success.”

Another group of community stakeholders interested in tracking CCISD’s efforts is the board of trustees, which Ebell said expects updates on special education reform.

Trustee Scott Bowen said it will be imperative to keep these conversations going once all the recommendations have been implemented. He said he will want substantial evidence that these recommendations made a difference.

“What I don’t want us to do is say ... ‘We implemented all of the recommendations, and now, we’re done,’” he said. “We can’t just say, ‘Well, we did it.’”

Board of trustees President Laura DuPont said district-level communication and execution of reforms has been and still is a challenge but that the program reforms tie into targets monitored by the board on an ongoing basis.

“Special education and those services—it’s the same as other units within the district,” she said. “Those children are no different; we want the same thing of all of our children.”