On the water outside, ships large and small move up and down the channel. Vessels carry liquid cargo such as oil and petrochemicals, and captains operate tugboats and towboats responsible for pushing barges loaded with dry and liquid cargo.

Inside the center, students learn the skills required to operate such machinery and succeed in the maritime industry. They learn through classroom instruction, realistic boating simulations and hands-on internships that put them on an operating vessel for up to 60 days, said John Stauffer, the college’s associate vice chancellor and superintendent of maritime.

“From a strategic standpoint, it couldn’t be a better place,” he said of the center’s location. “It’s on the water. Our customers are out there.”

Officials said the center is needed. J. J. Plunkett, port agent for the Houston Pilots, a group of master mariners responsible for navigating ships through the Houston Ship Channel, said the maritime industry is as important as the medical and energy industries to Houston’s economy. The maritime field is in need of young, educated workers eager to enter the industry, and the center will help fill the hole left by retirements, he said.

Despite opening in 2016, the center is already seeing success and recognition for its efforts in the maritime industry. The result is a training center that is growing annually in enrollment, making incumbent workforce training more convenient and filling gaps in the maritime industry.

“It’s just world class,” Plunkett said.

MEETING INDUSTRY NEEDS

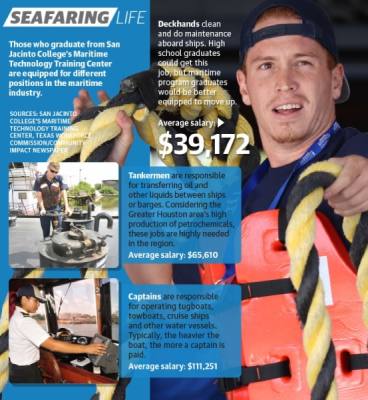

The maritime industry—which includes everything from cruise ship captains to tankermen who transfer liquid cargo between ships—has a growing need San Jacinto’s maritime center is helping to fill, Stauffer said.In recent years, the certifications the U.S. Coast Guard requires maritime workers to have to continue working on boats have gotten more intensive and time consuming. Many maritime workers who have been in the industry for decades decided to retire rather than return to school to relearn skills, Stauffer said.

Texas ports generate about 112,000 jobs related to marine cargo activities, but the exodus has created a shortfall in certain Houston-area maritime jobs, especially tugboat and towboat captains and tankermen, Stauffer said.

Gordie Keenan, the vice president of training at Kirby Inland Marine, is on the maritime training center’s advisory committee. He is one of many industry veterans who have realized the need to fill certain positions.

“Our business has transformed in the last 20 years. You can’t operate it without educated people,” Keenan said. “We were looking to find a way to hire better-educated people to get into our business to become officers on our vessels, so we started working with San Jacinto College.”

Any high school graduate can get a job as a deckhand, which is a person who helps with ship maintenance, is a lookout for a captain and performs other entry-level tasks. People who work as deckhands without a degree earn about $25,000 to $28,000 a year, but those with degrees make more and are better positioned to quickly advance, Stauffer said.

Additionally, there are four-year academies in the area, such as the Texas A&M Maritime Academy, that give graduates the ability to get major captaining jobs and other high-end positions sooner. Stauffer said maritime industry leaders and San Jacinto College officials realized about a decade ago there was a shortage of schools offering education to fill the midlevel jobs in between: the tankermen and towboat and tugboat captains the area needs.

“What wasn’t there was the middle space,” Stauffer said.

Those who graduate from the two-year training center leave with a certificate that allows them to captain a 200-ton vessel, which includes most tugboats and towboats. Many graduates start as deckhands but are able to fast-track within three to five years to becoming captains, who typically make six figures, but others might stop at tankermen and be comfortable making $80,000 a year, Stauffer said.

Students who graduate from the maritime training center are almost guaranteed a job right after graduation. So far, each of the center’s nearly 800 students have been given a paid internship between their first and second years, and each of them have been hired in the maritime industry after graduation, Stauffer said.

One such student is Jennifer Williams, who was so interested in the training center that she moved from New York to attend, she said.

Williams graduated in 2015 and now works as a Port of Houston mechanic and ambassador. Her goal is to work her way up to captaining the ship that gives visitors tours of the port, she said.

Williams spoke highly of the center and how it set her up for success. She believes the program will continue to fill gaps in the maritime field.

“The industry is still growing,” she said.

SIMULATIONS

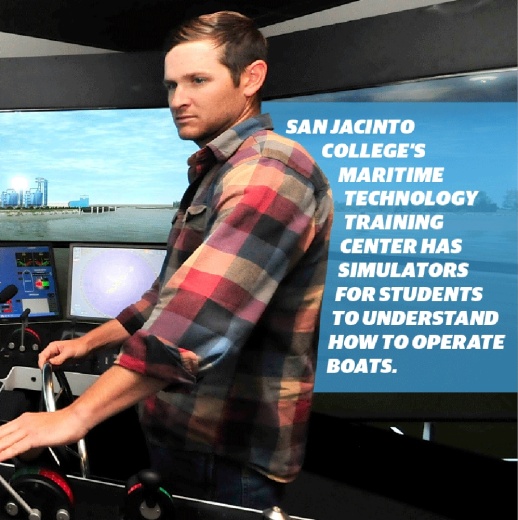

One of the major learning avenues between the classroom and getting hands-on experience aboard a boat is the maritime center’s simulators.The Houston Pilots donated three simulators worth a total of $1.3 million to the training center. The simulators feature controls that are identical to different types of boats students who enter the maritime industry might one day captain, Stauffer said.

The students use the simulators to apply lessons they have learned in class in a safer, more convenient environment than aboard an actual boat, Director of Maritime Simulations Bryan Elliott said.

Additionally, students who use the simulators could one day end up as Houston Pilots, which was one of their goals when donating the simulators, Plunkett said.

“The better the trained they are, the safer the ship channel will be,” he said.

The simulators are in dark rooms and feature various controls set up in front of a semicircle display of monitors that show a realistic display of the Houston Ship Channel as if the user were aboard a ship on the water. The simulators are so realistic that students report feeling like the room is rocking like a real boat, Elliott said.

“It’s almost always awe inspiring,” he said of students’ reactions to the simulators. “I just think we’ve had nothing but glowing reviews for the simulators [and] the simulation staff.”

The simulators are more than a fancy type of video game; the simulated ship channel is almost perfectly accurate to the hydrodynamics, layout and depth of the actual Houston Ship Channel. Besides captaining an actual ship, it is the most realistic way students can learn what it is like to control tugboats, towboats and other maritime vessels through the channel, Elliott said.

FUTURE GROWTH

The training center has seen steady growth over the years.Only 40 students enrolled the first year, but as of last year, 194 were enrolled, according to center data.

In addition to teaching recent high school graduates, the center trains industry professionals who use the facility to become recertified in their maritime-related skills. The center distributed 1,463 certifications in 2016-17 and 1,984 certifications in 2018-19, according to the data.

Despite the quickly increasing interest from students young and old, the center has plenty of room for planned growth. Adjacent to the center is land on which San Jacinto College this month will begin creating a fire field on which students can learn firefighting skills they need to enter the industry. The field, which will include various facilities, will allow students to train in firefighting skills without having to commute off-site, Stauffer said.

Officials are confident interest in the center will grow as more maritime companies realize its potential and students learn more about the lucrative jobs available at sea, they said.

“I think it’s gonna be a real key program to help us develop people as other companies get more interested ... about the programs there,” Keenan said. “I think the school’s gonna be great. Already it’s done, I think, an amazing job since it opened.”