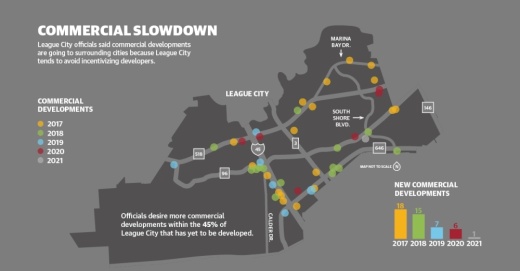

For the past five years, there have been fewer new commercial developments citywide each year. In 2017, 18 new commercial developments were built in the city, according to League City data. In 2021, an Amazon delivery center has been the only one.

Particularly, the city is having trouble attracting workforce-generating locations, such as office buildings, along with destination spots, such as restaurants and entertainment venues, said David Hoover, League City director of planning and development.

“Those are the kind of things we’re struggling to get,” he said.

City officials said there are some reasons for this trend, including League City City Council’s tendency to avoid incentivizing developers and relatively new roadway impact fees that are charged to developers in the city.

Some City Council members said League City’s benefits—such as its highly rated volunteer fire department and its location halfway between Houston and Galveston—should be enticement enough.

“There’s already that natural incentive,” Mayor Pro Tem Hank Dugie said.

Still, officials agreed it is crucial to League City’s long-term success to attract a greater percentage of commercial development in the city’s undeveloped west side than the city has today. Without new commercial developments, the property tax rate could increase once the city is built out, Hoover said.

“We’re missing the opportunity to attract these developers that are going elsewhere,” he said. “We are—right now as we speak, as far as I’m concerned—being left behind.”

Lacking in incentives

Riverbend is a planned multiuse development along Wesley Drive and I-45. The original plan was for the development to include high-end apartments, a hotel, a marina, an amphitheater, shops, restaurants and other amenities. To city officials, it was going to be a destination.

The $125 million, 69-acre development will not go forward as planned.

City Council in closed session over the summer voted down a plan that included the city incentivizing the developer, Clear Creek Point, with money to build the project within 7 1/2 years with the developer receiving no money if it missed certain timelines and benchmarks. With that deal dead, unless another agreement is reached, the development will now include only apartments and no public amenities, Hoover said.

City officials were disappointed by the decision, he said.

“We need one or two of these Riverbend or similar type developments to show that we’re capable of doing something like that because developers are like the trailblazers in the old West: Nobody wants to be first,” Hoover said.

Council Member John Bowen voted against the project. From his perspective, the Riverbend deal was not good for the city because it included investing in residences, retail and restaurants, Bowen said.

“The three R’s are something the city shouldn’t be chasing,” he said.

Dugie said he also opposes incentivizing developers, but he ultimately voted in favor of Riverbend because many amenities the developer planned would have been public.

Hoover said League City is losing out on developments to nearby cities—such as Webster, Pasadena and Dickinson—because City Council does not want to incentivize developers, typically through what are known as Chapter 380 agreements. According to the Texas Comptroller’s Office, these agreements for commercial and retail projects allow municipalities to offer incentives designed to stimulate business and commercial activity.

“When you’re sandwiched around entities that have money that they use for those [commercial development] activities, ... they have an upper hand,” said Council Member Larry Millican, who also opposes incentives.

Chapter 380 agreement payments to developers in League City have been decreasing. In fiscal year 2015-16, the city invested a peak of $1.42 million of public funds in private projects. In fiscal year 2020-21, which ended Sept. 30, the amount was about $458,000, according to city data.

Despite League City’s desire for commercial development, the city will not necessarily accept any development that comes its way, such as the numerous gas stations and convenience stores that apply for permits every week, Hoover said.

“We don’t want ‘em,” he said.

Roadway impact fees

Another factor affecting League City’s ability to attract commercial developments is roadway impact fees.

Roadway impact fees, which the city established in January 2019, are fees developers have to pay based on development type and location that go toward road projects made necessary by the developments. Residential developers are subject to pay $323-$3,632 per service unit depending on area, while commercial developers must pay $323-$560 per service unit. Service units are predetermined by development through a formula that measures the number of cars that pass along a road, the road’s length in miles and other factors.

Residents, City Council members and city staff have spoken positively about the fees; by the city collecting them, taxpayers are not subsidizing road work local residents believe developers should be paying.

League City is the only municipality in the Bay Area with these fees, which could put the city at a disadvantage when a developer is considering the cheapest place to build, officials said.

“Do the fees play into business owners’ calculations when deciding where to build? Probably,” Dugie said.

That is why in August, when City Council members considered raising roadway impact fees, they opted to keep the fees flat for commercial developments.

Had City Council voted in favor of the increases the League City Planning and Zoning Commission recommended, fees for commercial developments would have nearly doubled in some cases. Developers would not likely choose to bring businesses to League City when they can go to surrounding cities and not pay roadway impact fees, Hoover said.

The fees are not a total deterrent: Despite more than $90,000 in roadway impact fees and no city-provided incentives, Amazon chose to build a delivery station along Tuscan Lakes Boulevard this year. This is because company officials understood League City’s natural incentives as being the best place to locate, Bowen said.

However, Hoover said some city staff still disagree that League City’s amenities alone are enough to attract developers the city wants. Sarah Greer Osborne, director of communications and media relations for the city, agreed.

“If we do nothing, they’re not going to come,” she said. “We’ve got to play ball.”

Future goals

With League City halfway built out, officials must ensure enough commercial development comes to the city to keep the property tax rate, which has been steadily decreasing, from climbing back up, Hoover said.

League City residences and commercial properties make up about 85% and 15% of the city’s tax base, respectively. For the undeveloped west half of the city, the split needs to be closer to 50-50, Hoover said.

“It’s a big change to keep up,” he said.

Commercial developments are better for the city’s tax base than residential ones because they provide property, sales and other taxes, officials said. Additionally, commercial developments on average cost less for the city to service than residential properties, city officials said.

A few council members pointed out residences now generate more sales tax revenue under a law change that went into effect in October. When a homeowner makes an online purchase, the sales tax revenue generated goes to the city in which the buyer lives instead of the seller, which boosts League City’s sales tax revenue, council members said.

“We do have that going for us, but even still, once we reach build-out, it’s my opinion that we will need more commercial in order to able to fund the level of reinvestment that will be needed for our basic infrastructure,” Dugie said.

Another advantage of commercial developments is they attract people from outside the community to spend money in League City, which further bolsters sales tax revenue, Hoover said.

“It’s free money,” Hoover said. “Anything you can do that attracts that is the gold star as far as doing things in cities.”

If the city’s second half were to be mostly residential by its build-out three decades from now, the tax rate would have to increase to afford more police, fire and other needed services, Hoover said.

There are some projects on the horizon that could bring a commercial boon. For instance, the Grand Parkway extension is slated to carve through League City’s undeveloped southwest side, which will attract a slew of commercial development, such as office buildings, officials said.

Barbara Cutsinger, marketing manager for the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership, which promotes economic development across the Bay Area, said at an October League City City Council workshop that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, office development is booming nearby in Friendswood. Such developments could be a good fit for southwest League City, especially once the Grand Parkway extension is completed, she said.

“You want to be smart about what type of companies are coming in, but I think they’re going to be chomping at the bit to fill up that corridor,” Cutsinger said of the area.

Hoover said League City is primed for success.

“The opportunities that we have here are just absolutely enormous,” he said. “But we’re just missing a little vision.”