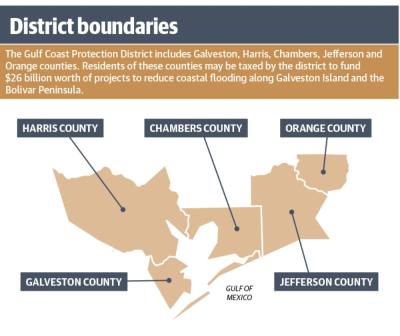

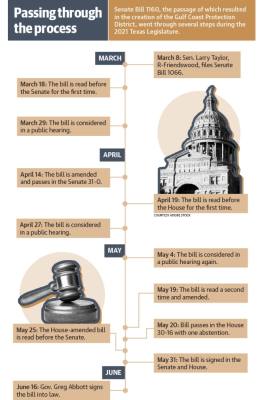

During the 87th Texas Legislature that ended May 31, legislators passed Senate Bill 1160, filed by Sen. Larry Taylor, R-Friendswood, and its House equivalent, House Bill 3029, filed by Rep. Dennis Paul, R-Houston. The passage of these bills created a district comprising five counties, including Harris and Galveston, that will act as an avenue through which the barrier and its related projects can be funded federally and locally, officials said.

The more than $26 billion set of projects will project residents and businesses from flooding caused by storm surge, as seen during Tropical Storm Beta in September 2020. Hurricane Ike in 2008 included storm surge flooding, costing the coast over $30 billion in damages, making the barrier a top priority, officials said.

“We get this thing built, it’s going to up economic development even further,” said Bob Mitchell, president of the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership.

Some residents have expressed concern about the district imposing a tax to fund the multibillion-dollar coastal barrier and related projects.

“People are so conservative, another taxing entity does not sound like a solution to them because it just means they’re going to pay more,” League City Mayor Pat Hallisey said of residents.

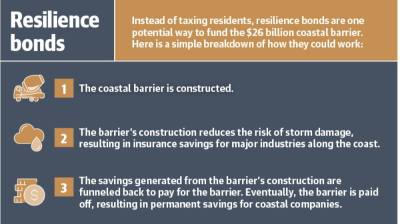

But district officials said there is another method being studied that could fund the barrier without the need for property taxes. Hallisey said he hopes this method, known as resilience bonds, is the solution the district needs to fund the barrier.

“This entity will have the ability to do all sorts of stuff, so I think this tax might be the last resort,” Paul said.

Potential taxing district

An October report from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regarding the coastal barrier is expected to go in front of U.S. Congress this August, when the federal government will decide whether to fund the project, Paul said.

“I want this region protected,” Mitchell said.

As such, legislators this session passed the creation of the Gulf Coast Protection District. On June 16, Gov. Greg Abbott signed the district into law.

The district encompasses Harris, Galveston, Jefferson, Chambers and Orange counties. An 11-member board will oversee the district with one representative appointed by each of the five counties and six appointed directly by Abbott, Paul said.

According to Paul and Mitchell, a member appointed to the board, the board will have the authority to issue bonds, impose fees and even create a tax on district residents to fund projects related to the coastal barrier, which includes a series of navigable gates between Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula, creating sand dunes along the coast to hold back storm surge, creating a barrier of seawalls around Galveston, and more.

Paul said the board’s taxing ability is one of the most restricted in the state.

“The board would say that they want to have a tax, but it would have to be voted on by the entire citizenry of the district,” he said. “So they can’t ever have any tax without the citizens saying, ‘Yes, we want to have the tax.’”

Paul said any district tax would be capped at $0.05 per $100 valuation, a limit that only the state Legislature could change in the future.

Mitchell said a tax likely would be only half of the cap, or $0.025 per $100 valuation. Such a tax would equal $75 annually on a $300,000 home—cheaper than annual flood insurance of a few hundred dollars. Furthermore, creating the barrier may result in lower flood insurance rates for residents, leading to a long-term net gain for taxpayers, officials said.

“It more than pays for itself,” Mitchell said.

Resilience bonds

The barrier and related projects are estimated to total just over $26 billion, 35% of which needs to be matched locally.

The project—which could begin as early as 2023 and take until at least 2041 to complete—goes along the entire Gulf Coast. However, the Bay Area portion—the part local officials care about—will cost about $10 billion to $14 billion, meaning local officials need about $3.5 billion to $5 billion for the local match, Mitchell said.

Despite the high cost, a tax might not even be necessary to fund the coastal barrier, Paul and Mitchell said. Instead, officials might opt to fund the project with resilience bonds, which is a way in which companies—not residents—would reimburse the cost of implementing the barrier.

Large companies along the coast, such as chemical and energy plants, pay significant amounts in flood insurance annually. Theoretically, after the barrier’s construction, these companies could use the money saved on their insurance costs to pay for the barrier. Using resilience bonds, as they are called, makes a lot of sense, Mitchell said.

“The idea is if you can prove to [these companies] this barrier will protect their assets, immediately they will begin saving money on ... insurance,” Mitchell said. “At some point, the bonds are paid off, and they’re home free.”

Shalini Vajjhala, founder and CEO of re:focus, a California-based company that helps groups with large resilience projects. For nearly a year, re:focus has been working with Bay Area communities on how to fund the barrier, she said.

“That value that’s created from greater protection can be recycled back to pay for the project,” she said of resilence bonds. “The aim here is to take benefits that are going to accrue over the 50-year life of this project and bring them forward to help pay for the project.”

Vajjhala compared resilience bonds to toll roads. When making a toll road, officials forecast how much it will be used, and the revenue from those tolls is used to pay for the road’s construction.

“We’re really trying to make a seawall look like a toll road,” she said of the barrier project.

There are several details to work out, including how to quantify the level of risk coastal companies face, which makes Mitchell hesitant to say he fully supports this funding method, though he does want to avoid a tax.

“Our deal is we don’t want to have to increase taxes,” he said. “Nobody wants a tax.”

Still, Vajjhala said it is possible to eliminate the need for a tax with resilience bonds. In fact, she said she has never seen a project with such a large return on investment, with the benefits of the project outweighing the costs at least two to one.

“We were blown away at the value that’s being protected,” Vajjhala said. “That tells you you’re protecting [something] of enormous economic consequence.”

Besides helping pay for the project, resilience bonds might help the project get done years sooner. Without a steady flow of money, the schedule will slip, especially considering the project’s scale, officials said.

“This will be the largest single engineering project the federal government has ever done,” Paul said.

This fact is incentivizing officials to secure local matching funds now, officials said.

“Everyone is better off for having done this project and done it quickly,” Vajjhala said. “This is the peak moment to get this project funded in full.”

Savannah Kuchar contributed to this report.