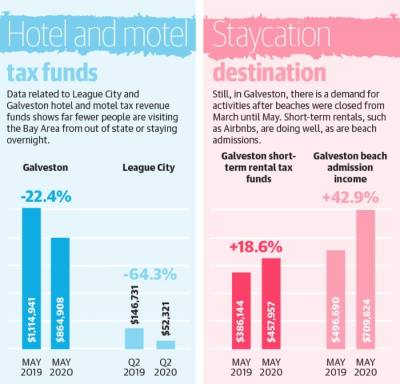

In Galveston, hotel occupancy tax funds—or tax income from hotels and motels that fund the Galveston Island Park Board, which promotes tourism—decreased dramatically. In May, the board saw nearly $865,000 in hotel and motel tax funds compared to $1.11 million in May 2019.

Galveston officials expect it will take three years before the island’s tourism industry returns to where it was prepandemic, and the city expects to lose some businesses along the way.

The problems are similar farther north, with the Bay Area and League City convention and visitors bureaus seeing economic downtrends since the pandemic began. Businesses relying on tourism, such as those near the Kemah Boardwalk, are suffering.

But that does not mean people are not traveling or enjoying the attractions Bay Area cities have to offer. Tourism groups are using what little budgets they have to entice nearby residents to come enjoy Bay Area activities, especially outdoors.

“We’re just trying to figure out the right way to adapt it ... and weather the storm,” said Stephanie Polk, manager of the League City Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Downward trend

In March, local hotels and motels began to feel the effects of the coronavirus pandemic as major cities shut down. People stopped traveling as much, and hotels have suffered.

In Galveston, July especially saw a big hit, considering beaches were closed July Fourth weekend. The Fourth of July is the single-biggest revenue day for businesses in coastal cities, said Kelly de Schaun, executive director for the park board.

“The loss of that weekend was significant to Galveston from a business perspective,” she said.

Polk said the pandemic’s effect on tourism in the area has been “unprecedented.”

“It’s changed everything,” she said.

The League City Convention and Visitors Bureau saw only $52,321 in second-quarter 2020 hotel tax funds. That is about one-third of the $146,731 the bureau collected in the second quarter of 2019.

Shawna Reid, the Bay Area Houston Convention & Visitors Bureau marketing and visitors center manager, said some areas, such as Space Center Houston and the Kemah Boardwalk, are starting to see more activity. Still, it is hard to predict how long it will take tourism to return to normal.

“It’s starting to pick up again, but it’s going to take some time for our hotels to recover,” Reid said.

Galveston is the fourth-biggest cruise port in the United States. That industry has ground to a halt, which has had a ripple effect across the island and Bay Area, de Schaun said.

One of the most popular tourist attractions in the Bay Area, Space Center Houston, closed in mid-March and did not reopen until July 19. The closure not only affected hotel stays and other businesses in the area, but CEO William Harris said he also does not expect to see nearly as many foreign or domestic visitors to the center until COVID-19 cases drop.

“People aren’t going to visit until we get our numbers under control,” he said. “It’s probably a real impact on hotels.”

Business effects

Because fewer people are willing to get on a plane or even in their cars to visit the Bay Area, local businesses are suffering despite being open. In Kemah, both newer and established shops fear having to close for good.

Courtney Sapp, the owner of Escape Kemah on Bradford Avenue, said the business is down 80% in sales compared to this time last year. The escape room was closed at least two months and reopened in the spring, but area residents have been reluctant to patronize the escape rooms, she said.

Once the Kemah Boardwalk opened up in early May, business got better, but the closure of bars at the end of June triggered another slowdown, Sapp said. They tried, without much success, to adapt the escape room model to include online games, she added.

Escape Kemah is offering group bookings only—four people for $100—so customers share rooms with only people they know, and the rooms are sanitized before and after each group. Prior to the pandemic, booking a full escape room cost $275.

“At least we’re able to make some money, but it’s still seen as a loss,” Sapp said. “That’s what we’re having to do just to keep the doors open right now.”

Sapp encouraged Bay Area residents to patronize small businesses.

“Just know that shopping local really helps,” she said.

Sandra Williams, who owns the Boardwalk Fudge shop just a block from Escape Kemah, agreed with Sapp.

“All the businesses here in Kemah are experiencing the same thing,” she said.

Boardwalk Fudge was closed for much of March and the first part of April. Sales lately have been largely from locals, with much less tourism than in previous years, Williams said.

Like Sapp, Williams said business picked up when bars reopened but has since slowed once they shut back down. She said she is unsure whether Boardwalk Fudge, which has been open 30 years, will be able to survive.

“We’re a small business, and right now we’re not even making our bills,” she said. “How long I’m going to be able to hang on, I don’t know, because this has already taken its toll on us.”

Meeting a need

When it comes to Bay Area tourism, not all is doom and gloom.

While hotel and motel rentals are down, short-term rentals, such as for Airbnbs, are going “gangbusters,” de Schaun said. In May, Galveston saw nearly $458,000 in hotel tax funds for short-term rentals compared to $386,143 in May 2019.

Tourism groups are shifting their focus from attracting out-of-state visitors to those nearby. The goal is to bring in locals dying to get out of their houses for a day trip to the Bay Area, officials said.

Tourists seem especially interested in outdoor activities, considering being outside results in a smaller chance of spreading COVID-19 than being indoors, de Schaun said.

“It seems to be where people feel the most comfortable,” de Schaun said.

In Clear Lake and League City, residents can rent boats and paddle along Clear Creek. The Bay Area is home to hundreds of species of migrating birds that are a popular attraction.

League City recently put up a billboard near Loop 610 that reads “The water starts here” to attract Houston residents to the city.

“We are safely marketing what we can to capture what business we can,” Polk said.

Galveston beaches closed at the beginning of the pandemic and did not open until May. When they did, people flocked to them. Galveston collected $709,623 in beach admission fees in May compared to $496,690 in May 2019, according to city data.

“There’s a great demand to be on the coast,” de Schaun said.

Karen Alexander, a nursing professor at University of Houston-Clear Lake, said several factors must be considered when families are planning recreational activities. Sanitizing, limiting exposure to the public, social distancing and wearing face coverings are essential, she said.

Swimmers are generally not wearing masks or practicing social distancing while in the water, which makes a day at a public pool or on the beach a moderate to high-risk activity.

“Any activity where no one is wearing a mask, and there is a high probability that you’re going to be touching your face, nose and mouth, you’ve reached a high risk there,” she said.

Officials are aware of the risk certain activities have. In fact, Galveston officials are not sure what popular island events such as Mardi Gras will look like during or after the pandemic, but figuring out how to plan such festivals is a good problem to have, de Schaun said.

“We feel really fortunate to be in a place that continues to have some demand,” she said.