The Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT, works to intervene before a mental health crisis occurs as well as to help officers responding to mental health calls, Smith explained.

“It’s meant to try to keep [people] from getting to that critical mass crisis state,” Smith said.

Assistant Police Chief Gary L. Tittle said mental health is a top priority for law enforcement agencies across the nation. Nearly 1 in 5 adults in the U.S. lived with a mental illness in 2019, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Bonnie L. Cook, executive director of Mental Health America of Greater Dallas, said Richardson having its own Crisis Intervention Team is a “fabulous idea.” She said police resources related to mental health are “spread so thin” that allowing individuals to focus on mental health as part of the solution is a “cutting-edge” practice.

“Mental health and mental illness is not a crime,” Cook said. “If we start working to provide people with mental illness with solutions—and we don’t treat [them] as criminals—then I think we are already starting in the right direction.”

Tittle said mental health issues do not excuse criminal behavior. However, he said officers can detain individuals having a mental health crisis rather than arrest them if they are an immediate danger to themselves or others.

“That is more often the appropriate detainment, and they do not come to jail, they go to [Methodist Richardson Medical Center] and go to their psychiatric center,” he said. “We just want to be diligent in our efforts to call [a mental health crisis] what it truly is and take the appropriate actions that should truly be taken.”

Smith said the Crisis Intervention Team worked its first case Oct. 1 and has since handled 84 cases, 50 of which are still active. Among the cases the team has handled are ones involving people who were suicidal and individuals dealing with issues related to depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

“We have certain people within our community that need extensive help,” he said. “And then a lot of these cases, it was just somebody that’s maybe struggled with depression their whole life and they lost their job due to COVID[-19]. Then one day they really just hit their wits’ end, and they felt suicidal.”

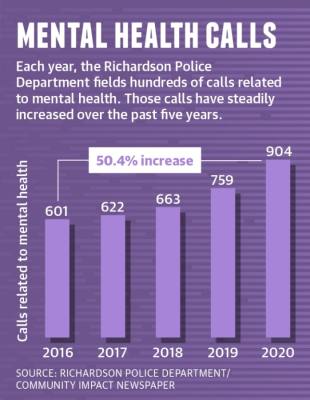

The department received more than 750 calls for assistance involving mental health crises in 2019, and those numbers ended up surpassing 900 in 2020 amid the coronavirus pandemic, Tittle said.

Mental health crises make up such a large chunk of the department’s calls that Chief Jimmy Spivey said during the Feb. 8 Richardson City Council meeting that intervening in any percentage would “have a huge impact on [police department] operations.”

Putting together the team

Tittle helped design and oversees the team, which includes 17 officers as well as a registered nurse and a social worker from Methodist Richardson.

The department’s goal for the team is to reduce the effect mental health-related calls have on police resources and to improve the lives of those needing help.

“The program is really developed to handle things on the back end,” Tittle said. “If we can do that follow-up work, what we end up doing is providing them a better quality of life [and] providing officers a safer environment.”

Follow-ups vary based on the individual, Smith said. Some people get help and do not need further assistance, while others may require extensive follow-up because of the “nature of the crisis involved,” he said.

The team also includes two school resource officers who work at campuses in Richardson ISD. Tittle said it made sense to include them because there are situations where students sometimes have mental health crises at school.

Officer Zach Kiper, who was recently promoted to detective, said he never had to deal with a mental health crisis during his time as a J.J. Pearce High school resource officer. But he said the Crisis Intervention Team, Methodist Richardson and Richardson ISD have a great support system in place for when those incidents do occur.

“Our only goal is to hopefully get juveniles in a school the help they need when they might not have access to that help outside of school,” Kiper said

That dual role as a school resource officer and a member of the Crisis Intervention Team is indicative of how the team was structured, Tittle said.

“CIT is [a] secondary assignment,” the assistant chief said.

He said Crisis Intervention Team work comes after an officer’s regular patrol or school resource responsibilities. The two sergeants that are in charge of the program are patrol sergeants on evening and overnight shifts, he said. But all the Crisis Intervention Team duties are voluntary, Tittle said.

“The cool thing in my mind is that we have 10% of our sworn personnel who want to be part of the CIT team without any type of additional stipend or pay,” he said.

Tittle said he does not expect there to be many additional costs for the department because the team is not bringing on any new personnel.

“There will be overtime costs, but we will use schedule-adjusting to mitigate some of that cost,” he said. “What we’re really trying to do is accomplish this program with no or limited fiscal impact to the [RPD] budget.”

The Methodist Richardson Medical Center Foundation is providing financial assistance for the team’s nurse and social worker. It also supports the educational training Methodist Richardson provides the team, staff said.

Training

While joining the Crisis Intervention Team requires 40 hours of training, Tittle said that is just the beginning of what members will learn.

Team members regularly attend Law Enforcement Mental Health Alliance meetings to stay current on best practices and trends related to mental health. The team also has monthly meetings with law enforcement agencies and hospitals in Dallas and Collin counties.

“We want our CIT members to be as highly trained as they possibly can be,” Smith said.

He said part of his role as one of the team’s sergeants is finding additional training on common mental health issues officers encounter in individuals.

“When [CIT members] arrive on calls for service with other officers, they can step up and hopefully have the tools in their toolbox to not only de-escalate those situations, but make those situations a positive thing,” Smith said.

The Crisis Intervention Team began informal operations in October; however, Tittle explained the registered nurse and the social worker from Methodist Richardson came onboard earlier this year. He said the department has provided those members some training, and Methodist Richardson has done the same for the team.

“We [all] recognize that de-escalation, time and space, and building a rapport is so important in dealing with those with mental health crises,” Tittle said.

Lauren Wetzel, Methodist Richardson behavioral health manager, oversees the hospital’s members of the Crisis Intervention Team. She said her staff is currently reaching out to a list of individuals identified by the Crisis Intervention Team as possibly needing further assistance.

“A lot of people just don’t know where to go to ask for the things that they’re looking for or how to fill those gaps of where they’re not even aware that they need support,” Wetzel said. “If we can help identify that and get them connected to the right programs, then I think we’re going to see a lot of positive outcomes.”

Implementation

In addition to providing the nurse and social worker, Tittle said Methodist Richardson is providing a 24-hour hotline officers can call for situational advice on handling a distressed individual. Wetzel said the police department has provided the hospital with contact information for more than 30 people who have been identified as needing mental health assistance. Hospital team members are helping to coordinate resources and support for those individuals, she added.

Even though work has just gotten underway, Spivey said the cases the team has handled have “been a bigger success than we even had hoped.”

“It has created an opportunity to recognize the enthusiasm we have on our staff—officers and, I’m sure, at the hospital as well—of people who want to help these people who are having mental health crises,” he said during the Feb. 8 meeting. “This is going to be a big thing for us.”