Brandon McCall was found guilty and sentenced to death for the murders of his friend Rene Gamez II and Richardson Police Officer David Sherrard. The death penalty for McCall signaled that while the practice is far less common, juries will still impose it for crimes they deem to be the most egregious.

The morality of the death penalty has been debated for years, but what sometimes gets forgotten is the toll capital punishment can take on a county’s bottom line.

Collin County District Attorney Greg Willis announced his intent to pursue capital punishment for McCall in April 2018. In his seven years as district attorney, Willis had never before sought the death penalty.

Willis declined to discuss the prosecution’s costs in this case but said he hoped a death sentence for McCall would send a message that the deadly assault of a police officer would not be tolerated in Collin County.

“When someone intentionally kills a police officer and says, in his own words, that he wanted to go to war with the police, that’s where we draw the line,” he said.

Understanding the decline

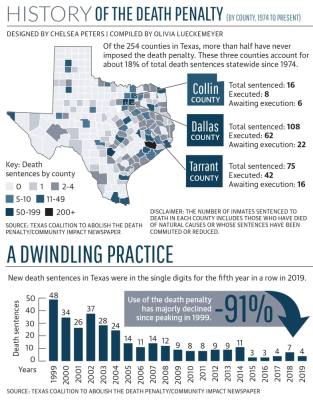

For years, Texas has been viewed as ground zero for the death penalty. It leads the nation in the number of executions since the practice was reinstated in 1974 and is among four states with the largest death row populations.

Dallas County is responsible for the second-most death penalty convictions statewide, but even it is not immune to the trend. Juries there have handed down just one new death sentence since 2014, according to Kristin Houlé, executive director of the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

The steadily rising cost of the death penalty has led some district attorneys to opt for the less expensive option of life without parole, Houlé said. This is especially the case in poorer, rural counties that cannot afford the death penalty, she said.

“We have a very arbitrary system of justice, in that the place where the crime was committed has a lot more to do with who gets the death penalty than the circumstances of the crime itself,” Houlé said.

A 2005 law that made life without parole a sentencing option for capital murder was designed to remedy this problem. It allowed district attorneys to avoid costly trials and appeals while also assuring a victim’s family that the perpetrator would never get out of prison, Houlé said.

Urban counties have more money to take on capital cases. But that is not enough to justify the practice, Dallas County Commissioner J.J. Koch said.

“Your plain, vanilla capital case requires Dallas County to spend considerably more on both the defense side and the prosecution,” he said. “Yes, a larger county can absorb these costs more readily, but is it worth it? That’s the question we should be asking.”

Weighing the cost

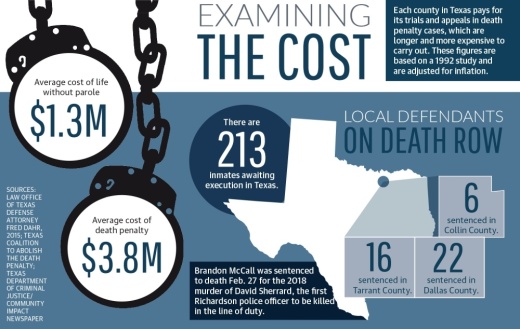

In Texas, each county pays for its own criminal trials and state appeals. Once an individual is charged, it takes at least two years for trial to begin, Houlé said.

“The meter starts running from the time the district attorney decides to seek the death penalty in a capital case,” she said.

The average cost of the death penalty is nearly three times higher than that of life without parole, according to Houlé’s coalition. That translates to an average of $3.8 million for the death penalty versus an average of $1.3 million for life without parole, according to a 2015 analysis by the Law Office of Texas Defense Attorney Fred Dahr.

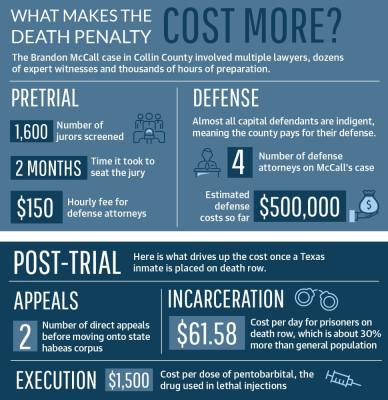

Because someone’s life is on the line, death penalty trials require a great deal of preparation, including individual juror screenings. In the McCall case, about 1,600 jurors were screened over a two-month period, according to Edwin “Bubba” King, McCall’s court-appointed defense attorney.

Death penalty trials also call for more evidence collection. With the advent of new technologies, such as the body camera footage presented at McCall’s trial, time spent combing through evidence has tripled, according to King, who said he spent a year and a half on the pretrial portion of McCall’s case.

“That sort of thing has tremendously increased the amount of time it takes to review the evidence that the state tenders to the defense,” he said.

At trial, death penalty cases typically involve more attorneys and expert witnesses. Capital defendants have the option of presenting mitigating factors that would not otherwise be admissible. Fees for mitigation specialists can add up to thousands of dollars, said Brad Lollar, assistant chief of the Capital Murder Division of the Dallas County Public Defender’s Office.

“Each one of these people is expensive; there’s no way around it,” he said. “And the judge knows that if he doesn’t approve the expenditure, [the outcome of the trial] is going to get reversed somewhere down the road.”

According to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, a defendant sentenced to death can appeal to the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals as well as the U.S. Supreme Court before moving onto the state habeas corpus process. The latter allows them to raise claims based on facts outside of the trial record, such as ineffective assistance of counsel.

A lawyer has been appointed to work on McCall’s direct appeals. This will be the first in a long line of attempts to get his case overturned, King said.

Taxpayers fund the $61.58 per day that the Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty reports it costs to house prisoners on death row. The average amount of time an inmate spends on death row prior to execution is roughly 11 years, according to the state’s criminal justice department.

Defense expenses

The majority of death penalty defendants, including McCall, are also indigent, which means county taxpayers pay for their defense. These costs far outweigh the prosecution’s end of the bill, according to defense attorney Toby Shook, who said he worked on at least 22 death penalty cases as the former assistant district attorney for Dallas County.

“The vast majority of cost is paying the defense attorneys and their experts,” he said.

King estimates that defense costs in the McCall case were roughly $500,000, most of which was attorney fees. There were three defense lawyers appointed to the McCall case as well as a fourth who was unappointed and worked mostly pro bono, King said.

Dallas County spends millions of dollars each year on defense in capital trials and appeals. The costs are split between the Dallas County Public Defender’s Office, which includes a dedicated capital murder division, and court-appointed private attorneys.

Lollar said the use of a court-appointed private defense attorney in Dallas County costs more than a public defender. Private attorneys appointed to capital cases in Dallas County are paid $150 per hour for out-of-court costs. During jury selection, which can take up to three months, they are paid $1,000 per day. Once trial begins, that fee jumps to $1,500 per day.

On the other hand, public defenders in Dallas County are salaried and do not bill for their time, Lollar said.

Collin County does not have a public defender’s office; instead, it appoints private attorneys to represent clients who cannot afford to pay. In fiscal year 2018-19, court-appointed attorneys worked 24 capital murder cases at a combined cost of $724,129, according to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission. The DA chose not to pursue the death penalty in all of those cases.

An argument in favor

The failure of the death penalty to act as a deterrent for murder is one of many reasons why Rick Halperin, director of the Southern Methodist University Embrey Human Rights Program, has advocated for its demise.

“From an economic standpoint, you might as well take all of this money and flush it down the commode because it does not do what it promises to do. It does not keep society safe,” he said.

Halperin is not alone in his view that money spent on capital punishment could be used elsewhere. In August 2019, Dallas County’s Koch proposed a two-year moratorium on the death penalty to study its financial and ethical ramifications. His proposal was not approved, but he plans to reintroduce it ahead of budget planning this fall.

“There is no life worth taking that has to be done so hastily,” he said. “We can spend time thinking about whether we want to do this or how we want to do this.”

Despite the cost, some people believe there are times when the death penalty is warranted. Richardson Police Chief Jimmy Spivey said he believes taking the life of a police officer deserves the ultimate punishment.

Sherrard was the city’s first police officer to be killed in the line of duty. His murder sent shockwaves through the department, and while his killer’s sentence brought officers a degree of closure, the loss of one of their own is still profoundly felt, Spivey said.

“There’s no real winners in this,” he said. “That verdict doesn’t bring David back. But it is justice, and we are happy that the person that did it has been held accountable.”•