The Collins-Arapaho Innovation District is a roughly 1,200-acre industrial area east of Central Expressway. Two decades ago, the district served as the supply chain to the city’s booming Telecom Corridor, which was home to some of the world’s tech giants, including Texas Instruments and Ericcson.

The area’s centralized location, access to talent and transit assets have made it a popular location for leasing activity. It is home to more than half of the city’s businesses and about 19,000 employees, a 2018 city-commissioned study of the area showed.

Despite all the district has to offer, limitations imposed by zoning have discouraged developers from revamping the area’s older buildings. In late December, City Council moved to spur redevelopment by approving sweeping changes to the area’s land use regulations.

“We’ve done just about everything we could do to remove barriers for reinvestment that is consistent with the vision [for the area],” Director of Development Services Michael Spicer said.

Now that the yearlong rezoning process has ended, revitalization can begin. Planning Projects Manager Doug McDonald estimates it will take between 10 and 20 years for the city’s vision to come to fruition.

TWO DECADES IN THE MAKING

The effort to revamp the Collins-Arapaho area dates back to the early 21st century, when the Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit research organization, was hired by the city to establish a vision for the area.

Following the dot-com bust of early 2001, several telecommunications companies supported by businesses in the district, including Alcatel and Nortel, were forced to consolidate or close. The event left behind “relatively high levels” of vacancy and functionally obsolete buildings, a 2013 baseline market analysis stated.

The land institute’s board strongly advocated for research, manufacturing and office developments as the dominant land use. But the board also encouraged the city to allow for other types of retail, restaurants and residential.

The city, which owns only one parcel in the district, could only do so much. In 2016, a Richardson Chamber of Commerce task force was formed to create a game plan for private investment in what would eventually become an innovation district.

The term “innovation district,” according to the Brookings Institute, refers to areas where large-scale companies are located near startups and business incubators. They are often physically compact, transit-accessible and technically wired and offer mixed-use housing, office and retail.

Richardson intended for its innovation district to be the “premier tech hub in Texas,” according to a 2018 vision statement. By allowing more uses and amenities, the area would attract both established and growing companies while also facilitating the success of existing businesses.

To accomplish this, the city set out to rezone the area in early 2019. The effort involved months of engagement with residents, the development community and current property owners.

AMENDING THE CODE

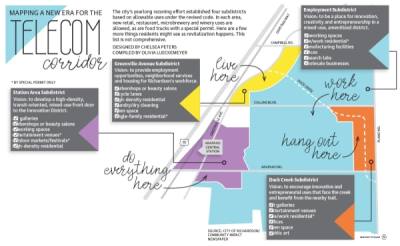

The rezoning effort established four subdistricts characterized by their allowable uses under the revised land use code. Those areas are the Duck Creek Subdistrict, the Greenville Avenue Subdistrict, the Station Area Subdistrict and the Employment Subdistrict.

The Employment Subdistrict makes up the bulk of the area. The intent was not only to support existing businesses but also to create an environment that will attract innovative companies and entrepreneurs, said Mark Bowers, the lead consultant with Kimley-Horn.

Allowing residential development only in certain areas of the Employment Subdistrict and by special permit only was intended to protect land values so that small businesses would not be priced out of the area, McDonald said.

“Where we landed is a really good place because it allows us the ability to look at it on a case-by-case basis,” he said. “If it becomes very successful and it’s something we want to expand, then we have the opportunity to do that.”

Most of the residential uses permitted under the revised code are live-work, multifamily and dense in nature. Single-family homes are allowed only in the Greenville Avenue Subdistrict and only with a special permit.

Perhaps the most important landmark in the area is the Arapaho Center Station, which the city envisions as the gateway to the innovation district. City staff is now meeting with DART on a monthly basis to figure out how best to position the station as a catalyst for development, McDonald said.

One of the ways the city is looking to leverage the property is by partnering with local school districts and higher education institutions, such as The University of Texas at Dallas and Richland College, to create a business incubator inside the station, McDonald said.

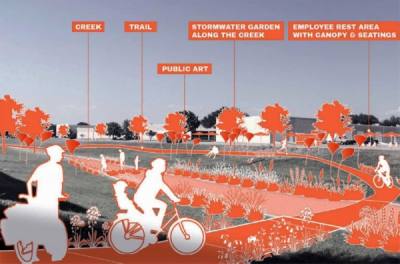

The code also establishes allowable street types; building heights and setbacks; signage; and open space requirements. Mobility improvements, such as dedicated bike lanes and widened sidewalks, are proposed for some of the key streets in the district. On Greenville Avenue, temporary bike lanes will eventually become permanent, McDonald said.

NEXT STEPS

Now that rezoning is complete, the city is setting its sights on promoting private development.

“We can help ready the environment for the private sector to come in, but we really have to rely on those individual property owners to start making those improvements,” McDonald said.

The city owns only one property in the district, located at 1302 E. Collins Blvd. Talks are underway on how to position that property as a catalyst for further development—whether that be repurposing the building or using revenue from its sale to reinvest in the district, Spicer said.

“That is perhaps our most significant asset in the area, aside from our infrastructure components,” Spicer said.

The city is also not opposed to buying up some properties in the area, McDonald said. That strategy has proven successful in the up-and-coming Main Street area, he added.

Another effort aimed at garnering attention from the development community and residents is a rebranding of the district. Richardson Chamber President and CEO Bill Sproull said a new name for the district should be announced by the end of January.

The chamber task force is also continuing work on its plan to recruit innovative and entrepreneurial companies to the area, Sproull said.

“One of the features of an innovation district that is really important is that you have this networked entrepreneurial culture where people and companies and researchers all interact and collaborate,” he said. “But you need some kind of facilitation for that.”