The 27-acre parcel of land, known as Owens Spring Creek Farm, has been zoned industrial since the 1960s. Part of the property was home to the Owens Country Sausage plant until its demolition in 2013.

The need for a zoning change was triggered by the request for single-story buildings that would be 44 feet tall, a height normally reserved for two-story buildings. Under the allowed zoning, one-story buildings are limited to 29 feet in height, the city's Development Director Michael Spicer said.

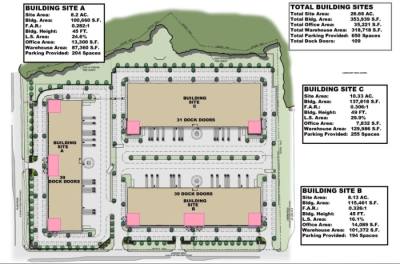

The developer, Crow Holdings Industrial, planned to build three spec warehouses totaling about 354,000 square feet.

“Sites like this that are currently zoned [industrial] don't come around that often, so this site is highly attractive for the project we propose to build,” said Will Mundinger, founding partner and senior managing director for Crow.

The buildings would have been catered toward tenants seeking between 20,000 square feet and 50,0000 square feet, which Mundinger said are the “bread and butter” of Richardson and neighboring Plano.

“We want to appeal to tenants that are already in the neighborhood,” he said.

More than 100 truck docks were included in the plans, which raised concerns over the amount of traffic generated by the site. A study commissioned by Crow found that the number of vehicle trips to and from the development would total 935 per day, which would increase traffic on surrounding roads by just over 2% during morning peak hours.

The city received 99 pieces of correspondence in opposition to the project and one in support. Seventeen residents signed up to speak against the project during the Jan. 25 City Council meeting.

Charline King said the development would “forever change” her neighborhood’s quality of life.

“No amount of concessions will nullify that this is 22 acres of a concrete warehouse distribution center in a greenbelt next to residences and a golf course,” she said.

Evelyn Roberson echoed King’s sentiment, stating that the site’s industrial zoning was acquired during a time when the majority of the surrounding area was farmland. Today, there are no other industrial properties within several miles of the property, she said.

“It’s just an oddball thing that occurred,” Roberson said of the zoning. “It just does not fit into this area.”

Concerns of increased flooding from the adjacent Spring Creek were also voiced by residents. The property is located within a floodway and abuts an 100-year floodplain designated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, according to city documents.

Spicer said peak flow levels from the Spring Creek watershed would occur much earlier than the location of the site. A study commissioned by Crow also found that the development would not increase flood risk.

This is not the first time a proposed development on this land has been opposed by residents. Last fall, landowner Standridge Companies proposed a mixed-use project that would have included retail and residential properties.

When an overwhelming number of residents came out against the project, Standridge chose to forgo the development, founder Stacy Standridge said. His team told neighbors that an industrial proposal would likely follow, he added.

Standridge said his company chose Crow from a list of high-profile industrial developers because it was willing to make concessions that would appeal to neighbors.

In the days leading up to the meeting, Crow agreed to decrease the City Plan Commission-approved building heights from 50 feet to 44 feet. The company also offered to build a sound wall to mitigate noise caused by idling trucks, Mundinger said.

“We have been making sure that both neighbors and elected officials understand that to the extent that there are things we can do to improve the project in the eyes of the neighborhood, we are willing to do,” he said.

Council Member Janet DePuy said that if the request was denied, the developer would likely return with a new industrial use that does not require a zoning change, leaving the city without “any negotiating power.”

“You must come together to figure out what is the best concession for the area,” DePuy told the neighbors in attendance. “You’ve opposed two different types of development—what do you want there?”

Many neighbors said they would like to see the city purchase the property and turn it into a park. Mayor Paul Voelker said this was out of the question due to the cost.

“You have more green space than any other neighborhood in the city,” Voelker told residents in the audience. “We are not going to make a park out of it.”

The prospect of industrial development should have been taken into consideration when neighbors bought their homes, Council Member Mark Solomon said.

“Not one house has been built there, to my knowledge, when that area was not already zoned industrial/commercial,” he said. “Did you ask your Realtor what the land was zoned for?”

In the end, council members voted 5-2 to reject the zoning change. Solomon and Mayor Paul Voelker opposed the motion.

“I really do want to make sure everyone understands that my vote really represents that this is not going to be a city-acquired park,” Voelker said. “We are going to have to roll up our sleeves and figure out what we can put in there.”