Zhenpeng Qin, associate professor of mechanical engineering at UT Dallas, began studying rapid diagnostics nearly a decade ago.

The project Qin is working on now stands not only to improve disease detection but also to cut down on health care costs by eliminating the need for costly lab visits.

“The goal is to make a rapid assay that doctors can use and can tell with great confidence whether their patient has the infection or not without needing to refer to a lab to do a backup test,” he said.

Qin recently received a $293,000 grant from the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program to advance the test’s ability to diagnose the flu.

Rapid flu tests available at doctor’s offices misdiagnose anywhere between 30%-50% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control. To get an accurate result, samples must be sent to a lab, Qin said.

“Sensitivity is a really big issue for any rapid diagnostic test,” Qin said.

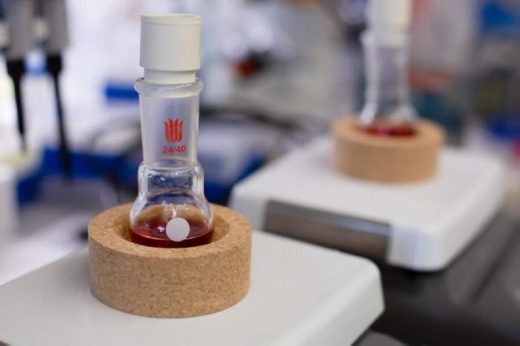

Qin’s method mixes a patient’s sample with a gold nanoparticle reagent that can detect the presence of a virus within 15-30 minutes. Doctors are able to accurately diagnose an infection without ever leaving their office, he said.

Much of the cost associated with currently available tests is tied to labor and equipment used in the lab, Qin said. The reagent needed to conduct Qin’s test can be made at a reasonable cost, he said.

“If the test doesn’t involve a lot of labor and you can do it quickly while the patient is visiting the office, ... then, we are really talking about a great cost reduction,” he said.

Qin’s method can also be used to test for COVID-19 and its antibodies, he said.

“This test can be quickly redesigned or modified to detect new, emerging viruses,” he said.

The next step for Qin is to find a startup, licensing or a nonprofit organization to help get the test approved by the U.S. Federal Drug Administration and into the hands of doctors. He said he envisions the test eventually being used in hospitals and clinics as well as by patients in their own homes.

“There’s always a gap between the academic research and the real-world application,” he said. “We are trying really hard to close this gap.”