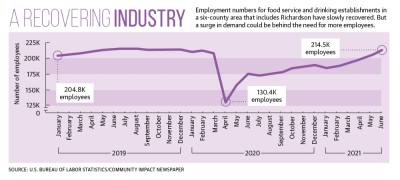

Nearly 211,000 employees were working in food service and drinking establishments throughout the six-county area that includes Richardson in January 2020, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Four months later, following widespread closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, that figure dropped to almost 130,000 workers. As of June this year, service industry employee numbers had climbed back to more than 214,000.

Still, many local restaurants say it is difficult to find workers. Nick Barclay, owner of Fish & Fizz, said he believes there is a confluence of factors driving the service industry’s extreme worker shortage, including career changes, disillusionment with the job and an apprehension toward working in close quarters. But perhaps the biggest reason, Barclay suspects, is the speed at which restaurants reopened.

“It always takes longer to wind something up again than it does to shut it down,” he said.

The trend of worker shortages is harmful to any economy because it typically means businesses have to outsource labor to meet demand, Richardson Chamber of Commerce President and CEO Bill Sproull said. However, the effect on Richardson is not as severe because of its diverse base of business, he said.

“We are not a service sector-heavy economy that relies on restaurant and retail workers or hospitality workers for the bulk of our economy,” Sproull said. “Our key sectors are in technology, finance and insurance, and they’re all extremely stable.”

Switching careers

Richardson resident Siraham Lerma spent 20 years working in various bars and restaurants in the Dallas area. Lerma said he never thought of doing anything else and had planned to open his own bar one day.

While on furlough during the pandemic, Lerma said most of his coworkers were making nearly as much in unemployment payments as they were when they were working. Lerma said he decided not to file for unemployment. He was eager to return to the bar where he worked, he said.

“I was the first one to come back and the only one for a while,” Lerma said. “Because nobody wanted to come back.”

Tired from the long hours and looking for a lifestyle change, Lerma said his girlfriend convinced him to look at other jobs. At first, Lerma said he was not sure he was qualified for anything else. But he soon landed a remote job for Geico selling insurance.

“I really did love the service industry,” he said. “But this career change has been really positive for me. My girlfriend makes fun of me because ... I roll out of bed, have my coffee, walk the dog and then I’m just in my office, working from home. I love it.”

Karen Musa, executive dean at Collin College with an extensive background in hospitality and food service management, said restaurants being forced to shut down or transition to different service models caused financial stress for employees.

As businesses reopened with restrictions, employees who relied on tips were not making what they used to, said Musa, who helps oversee the institute of hospitality and culinary education at the college.

“A lot of people did move on because they had to support their families,” Musa said.

The combination of customers dining out more often and restaurants hiring less experienced employees may be contributing to a perceived staffing shortage, Musa said.

“The public ... is wanting to get back to normal,” Musa said. “But a lot of [restaurants] are not ready for that.”

Considering unemployment

Gov. Greg Abbott announced in May that Texas would opt out of further federal unemployment payouts related to COVID-19 as of June 26, citing an abundance of jobs as well as fraudulent unemployment claims. This included the loss of a weekly $300 supplemental benefit, a move that some said helped push people back to work.

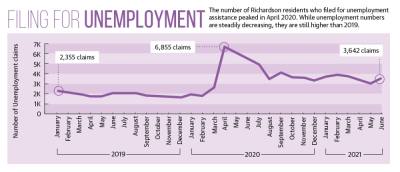

In Richardson, the number of residents receiving unemployment benefits peaked at 6,855 in April 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Those numbers are closer to 3,600 as of this June but are still much higher than all of 2019.

Jordan Swim, a partner at Richardson restaurant Pizza Americana and president and partner of Vestal’s Catering, said the removal of unemployment benefits related to COVID-19 did not result in an uptick of applicants at either of his businesses. He thinks former members of the service industry—either out of necessity or convenience—chose to explore other careers.

“I don’t think it’s about unemployment,” he said. “I think everybody’s trying to reassess ... ‘What am I doing with my life?’”

Putting workers first

The pandemic forced many restaurants to lay off workers, and, when given the opportunity, some chose not to return.

But business owners who found creative ways to avoid layoffs are now at an advantage, Swim said. The creation of Furlough Kitchen, a popup nonprofit that served meals to out-of-work hospitality workers, was Swim’s way of keeping his core staff employed during the pandemic.

“They’re still here, and they’re thriving,” Swim said. “That’s been a really good consistency aspect of our business.”

A strong investment in people is one of the best ways to remain competitive amid an extreme worker shortage, Barclay said. Fish & Fizz offers a four-day work week, which Barclay said is a benefit that is hard to come by in the service industry.

“The restaurant business is notoriously hard [with] long hours and not much time off,” he said. “So ... that is what we are trying to do to compete in the labor market.”

As restaurants try to navigate ever-changing rules and a choppy return to normalcy, Swim encouraged diners to be kind to service industry workers.

“Be patient with your local restaurants,” he said. “They are trying the best they can.”

Emily Jaroszewski, Anna Lotz and Erick Pirayesh contributed to this report.