The department services a 72-square-mile area that makes up Plano. Along with Collin County Animal Services based in McKinney, the two departments are responsible for all of Collin County.

As one of the largest shelters in North Texas, Plano has not euthanized an animal because of lack of space for over a decade, Animal Services Director Jamey Cantrell said.

A decline in volunteers due to COVID-19, a surge in adoptions during the pandemic, efforts to fill multiple vacant positions and the creation of a new city ordinance allowing backyard chickens have all contributed to the workload, he said.

But through all of it, he said, saving as many animals as possible remained the No. 1 goal.

“When [COVID-19] hit, everybody was told to work from home. But we can’t do our jobs from home,” Cantrell said. “We work 365 days a year, [and 2020] was no different.”

While cats and dogs make up the majority of animals in Plano, the department handles other animals as well. That includes bobcats, snakes, coyotes, cattle, horses, raccoons, rabbits and even exotic birds.

Some, like Scarlett, the red-and-blue eclectus parrot, never leave. The bird, native to the Solomon Islands near Australia, has lived at the Plano shelter for over 10 years after flying into a resident’s house. After no one adopted her, the staff decided to keep her.

“She’s like the shelter mom,” Cantrell said. “She’s smart and also sassy.”

He said the shelter sees up to 20 new animals each day.

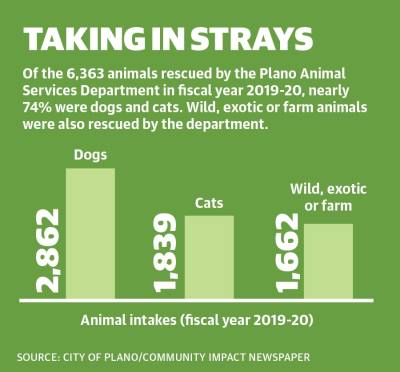

Since 2016, data shows the department has taken in nearly 30,000 animals. It has been able to safely rehome most of them.

A rise in adoptions

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals reported in May that nearly one in five households nationwide adopted a pet since the beginning of the pandemic. And over 85% of those households still have those pets, the report said.

“This incredibly stressful period motivated many people to foster and adopt,” ASPCA President Matt Bershadker said in a statement.

Cantrell said Plano also saw an uptick in adoptions the last two years but has not seen an increase in returns. He said with more animals and people in the city, it has led to more work for the department’s staff.

“It is going to be a continuous upward trend until Plano’s [population] kind of levels out,” he said.

During the 2019-20 fiscal year, the department’s service officers went on over 8,000 calls to pick up or rescue animals across the city.

A position of need

Plano has 18 full-time animal service officers. But the budget allows for 21 officers, Cantrell said.

“Overall, staffing is our biggest hurdle right now,” he said.

Cantrell said hiring the right people can be difficult. The position requires someone with a unique skill set.

Animal Services Officer Molly McLaine has been with the city since 2012. She said growing up watching the television show “Animal Cops” inspired her to want to work with and help animals.

The job is about more than just wrangling stray pets, McLaine said. Rescuing lost or wild animals, cleaning kennels, dealing with owner surrenders, responding to calls, working dispatch and even helping the shelter’s veterinarians with surgeries are all duties that officers handle.

“We go wherever we are needed most,” she said.

McLaine said the department is not for everyone. The emotional toll of seeing animals returned by their owners or euthanized due to illness can push some to find work in another field, she said.

“The staff is all pretty close to one another, so that definitely helps,” she said. “We can always relate to whatever that person’s going through.”

Backyard chickens approved

Another duty the Plano officers are now responsible for is regulating backyard chickens.

After receiving direction from City Council in June 2020, Cantrell began rewriting the city’s animal ordinance code to allow backyard chickens.

Council approved the change in a 7-1 vote in September.

The ordinance states residents must be approved for a permit before owning chickens.

Cantrell said as of early December no one has been approved yet, but three residents have applied for permits.

The cause to allow backyard chickens started when residents with the Plano Hens Facebook page said owning chickens is a property right.

Plano City Council Member Rick Grady, who voted against the ordinance, said at the Sept. 27 meeting he could not support the change.

“We ... forget all about other homeowners that may not want to have chickens,” he said.

McLaine said neighborhood chickens are not as simple to care for as some residents might think.

“I’m not a fan,” she said, but added that the ordinance means “the chickens will be raised in the most humane and sanitary environment we can ensure.”

Ways to help

While backyard chickens may add extra work, a recent benefit Cantrell said has been the return of in-person volunteers.

Because volunteering was paused due to the pandemic, Cantrell said there is a back-log of training and orientations.

He said getting volunteer hours back is a top priority for the department. “We had built it up to where we were getting over 20,000 hours a year of volunteer time,” Cantrell said. “COVID[-19] hit, and you could easily say it was cut in half.”

Cantrell said the department is fortunate to have a strong volunteer base while being well-funded through the city and private donations. He said it allows them to save more animals than cities with less funds.

“We have spent thousands of dollars on an animal to get them well,” he said. "It is not about the money if we have the ability to improve the animal’s life.”

Plano Animal Services has a budget of nearly $2.6 million for fiscal year 2021-22. It also receives about $4,000 a month in private donations.

Having visited other shelters across North Texas, McLaine said Plano uses its resources the right way.

“Working here, we get to see [the animals] go home unless they are aggressive or ... sick to the point we can’t provide the proper medical care,” she said. “Luckily, they usually wind up getting adopted and going home.”