The state of Texas this year is scooping up record levels of Plano ISD property taxes, part of a steep uptick in state recapture payments that is expected to continue for the foreseeable future, district officials have said.

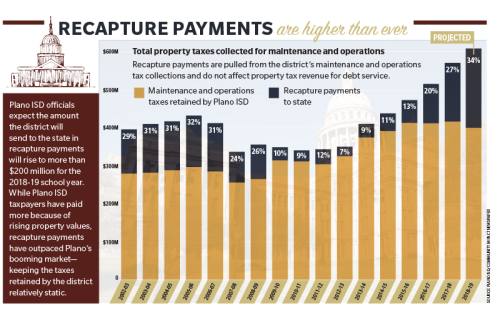

Of the $573 million PISD will collect in property taxes this year for its day-to-day operations, nearly $155 million will be sent to the state—a record-high recapture payment. Next year’s payment is expected to rise by an additional 32 percent and cost the district more than $200 million.

And while the state is adding to its overall education budget through these property tax revenues, some PISD officials are crying foul. Pointing to the state’s declining share of contributions to public education, PISD officials have said recapture payments are making up the difference for a decrease in state funding.

Lawmakers have pushed for structural changes to recapture payment policies in recent legislative sessions but have failed to pass legislation that affects how much tax revenue property-wealthy districts send back to the state.

In terms of school-finance legislation, recapture policy reform is not a priority for all lawmakers, as districts subject to high recapture payments like PISD are outnumbered by districts that do not make payments, said state House Rep. Jeff Leach, R-Plano.

Under existing formulas, PISD Chief Financial Officer Steve Fortenberry said the district projects it will continue to forfeit climbing tax revenue payments to the state for the foreseeable future.

“The only way [the rise in recapture payments] will end would be when our property values, locally, stop growing,” Fortenberry said. “As property values grow, we become a wealthier district; therefore, the state takes more of our property taxpayers’ money to use for the state budget.”

Recapture payments on the rise

While property value growth plays a key role in increasing recapture payments, not all property-wealthy school districts pay into recapture. PISD is particularly prone to increasing recapture payments because of a recent stagnation of student enrollment rates.

In fact, 54,322 students enrolled in PISD schools in 2016, which is a drop of 76 students from the year before, according to Texas Education Agency reports.

The decline in student enrollment combined with rising property tax revenues—a result of Plano’s booming housing market—has been the driver for higher recapture payments for school districts like PISD, TEA Information Specialist Lauren Callahan said.

In stretches of economic prosperity, especially in regard to an appreciating housing market, increased property tax revenues have a direct effect on how much the state contributes to its education budget, according to a document from the state’s fiscal analysis agency.

The Legislative Budget Board’s 2016-17 biennium report says the state’s share of public education funding is projected to decrease due to recent property value growth.

And as the housing market has improved in the last nine years, the state’s contribution has decreased from approximately 45 percent of the public education budget in 2008 to 38 percent in 2017, according to the report. Local tax revenues make up the bulk of the difference, according to the report.

“[Plano ISD is] a cash cow, and more cash cows are being created every day,” PISD board of trustees President Missy Bender said.

Where is the money going?

At its core, recapture policy was set in place to send revenue from the property-wealthy school districts to property-poor school districts.

However, because the TEA’s funding for public education is distributed from a single fund, the TEA does not report where dollars sent to property-poor districts come from, Callahan said.

“We could tell you how much recapture came in, and we can tell you how much each district got, but there is really no difference between a recapture dollar and a lottery dollar. They are all in the same pot,” Callahan said, referring to the state’s practice of using some lottery revenues to fund public education.

Still, when a district’s property values rise, the state’s share of contributions decline—even if the district is considered property poor, Callahan said.

Fortenberry points to the imbalance between higher recapture payments from property-wealthy districts and declining subsidies to property-poor districts as one of the breakdowns of recapture policy.

“It’s obvious that if [property-poor districts] are getting less money and we are paying more money, then our money is not going to the property-poor districts,” Fortenberry said.

Bender said a recent increase in franchise tax relief and homestead exemptions reported on the LBB’s 2016-17 biennium analysis could be one of the sources of where state dollars are being spent.

“Effectively, [recapture] is a state-imposed tax that the taxpayer should be informed about,” Bender said.

Although recapture payments are funneling tens of millions of dollars away from PISD, not all district expenses are affected by the decrease. Property taxes sent to PISD are broken up into two categories: taxes collected for maintenance and operations, and those collected to fund debt service. Bender said recapture only affects maintenance and operations, the higher of the two tax rate components.

Limited traction in Legislature

Taxpayers in Plano and other property-wealthy districts may continue to eat the costs of rising recapture payments, as the burden only falls on a select few districts, said Leach, the Plano state lawmaker.

“You look at Plano, Highland Park, Austin, Southlake—there are very few, if any, school districts that have the burden that Plano has in terms of recapture payments,” Leach said.

An early version of House Bill 21 proposed to decrease the amount of recapture payments required from property-wealthy school districts, among other school finance reform policies. But those reform provisions were not part of the final bill.

Recent efforts to inform Plano taxpayers about the climbing recapture payments are not the first attempts district officials have made to promote changes to recapture policy. In 2005, PISD was part of a lawsuit that resulted in the compression of the maximum amount a district could collect in property taxes—requiring the state to foot the bill for the difference.

Bender also testified in March at the Capitol for a bill that would require the state to report on residents’ property tax bills how much it was collecting in recapture payments. That bill was left pending in the House Ways and Means Committee.

Leach said achieving meaningful legislative change, especially for something as complicated as school finance reform, has been historically difficult.

“The fact of the matter is, we considered over 6,000 pieces of legislation, and nearly 5,000 of those bills died,” Leach said. “The system is set up so it’s hard to pass legislation. And many times, big substantial legislation like school finance reform takes several sessions to pass.”

The Legislature is establishing a school-finance commission to make recommendations and help settle the debate for the next legislative session, Leach said. But that session will not begin until 2019, leaving room for recapture payments to continue growing.

“The system is designed so that we are going to be at that very same point in time again, [as we were before the 2005 lawsuit],” Bender said. “So, if the state says, ‘We don’t have a statewide property tax,’ then prove it.”