Alan Johnson is one of those trying to help. For the last year, the Plano resident has headed the Plano Census 2020 Complete Count Committee, a group the city tasked with working with local organizations to ensure an accurate count.

“Our whole point over the last year has been to focus on promoting the census and informing people that it applies to all residents,” Johnson said. “[We tell them that] it’s safe and secure, [that] your information is held secure for 72 years and that it’s very important to them for the services that go to them, and particularly to their children to complete the census and turn it back in.”

Some Plano residents are at a higher risk of not being counted. Census takers consistently have a difficult time counting immigrants, young children and people who are homeless or disabled, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Hispanic and Latino residents are also often hard to count, partly because they sometimes face language barriers. These residents also tend to be more suspicious of how census data is used, which also makes them more likely to be undercounted, the bureau said.

Because of its size, Texas is the third-largest recipient of federal funding allocated based on census data, according to the Texas Demographic Center. An undercount of the state’s population by just 1% could result in a $300 million loss in federal funds, according to the center.

An undercount could greatly affect funding in several key areas, said George Tang, the managing director of Educate Texas, which has worked with Collin County groups to promote the census.

“We would need to make significant cuts that would impact critical areas in our community, like education, health care, roads, infrastructure and more, for the next 10 years,” Tang said.

The census also affects students in Plano ISD, which receives millions from the federal government to help fund school lunches and other programs. For the first time, the census count will also affect how much the district receives from the state each year for programs for disadvantaged and at-risk students.

“The more economically disadvantaged students you have, based on census data, the higher the allotment sent to the district will be,” PISD Chief Financial Officer Randy McDowell told trustees Feb. 18.

Census data is also used to determine the number of congressional seats and electoral college votes each state has.

A diverse Plano

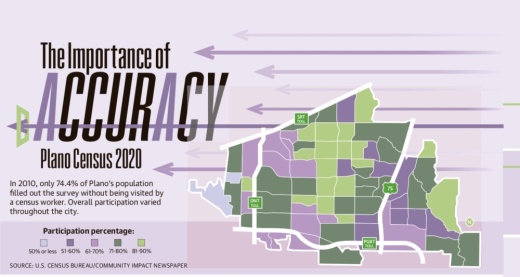

In 2010, Plano was home to the seven census tracts in Collin County with the highest concentrations of non-English-speaking households, according to that year’s American Community Survey.

Each of those seven Plano neighborhoods responded to the census that year at rates lower than the city’s overall mark of 74%.

The census uses statistical methods to fill in the gaps. But the less representative the initial count is, the less likely it is that the final results will be accurate. That is a scenario Johnson and others in Plano are determined to avoid.

“There’s an old term in business—’garbage in, garbage out’—and if you get as accurate of a count [as you can] at the start, you’re going to get a more accurate reading at the end,” Johnson said.

To prevent undercounting, Johnson’s committee has been working with local groups to raise awareness among residents who might be reluctant to participate.

Committee members have stopped by Plano religious congregations, Hispanic and Asian grocery stores and other public places to hand out informational materials and talk about the census.

The Collin County Business Alliance has also invested time and resources to ensure an accurate count, CCBA Director Barbara Baffer said. The organization held a Collin County Counts workshop in February with local nonprofit groups who work with historically undercounted communities.

“The Collin County Counts initiative is focused on how to engage, educate and ultimately count the area’s increasingly diverse and growing population,” Baffer said in a statement. “The workshop’s tools helped alleviate concerns nonprofits may have with the census process.”

Residents are less likely to respond if they are not sure how the government plans to use the information it gathers, Johnson said, while others are under the false impression that the census includes a citizenship question, a point census workers and local volunteers are working to dispel.

Bianca Gamez, media specialist with the Dallas Regional Census Center, said all individual census data is kept confidential. She said that every census worker takes an oath to do so, and any workers who breaks that oath could be fined $250,000 and potentially face jail time.

What to expect

Residents have begun receiving mailed invitations to respond to the census, according to the bureau. Those who do not respond will receive several reminder postcards before being visited by a census worker, said Sue Linder-Linsley, assistant regional census manager for the Dallas region.

For the first time, citizens will have the option to respond online in addition to by phone or by mail. The bureau expects that this option will encourage more citizens to respond, Linder-Linsley said.

Gamez said the bureau will track which households respond so it can send workers to those that have not.

“This is going to be a big census for us,” Gamez said.

Anna Herod and Olivia Lueckemeyer contributed to this report.