As more businesses struggle to hire staff, especially those in the service industry, companies are willing to go to new lengths to find workers.

Nearly 211,000 employees were working in food service and drinking establishments throughout the six-county area that includes Plano in January 2020, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Four months later, following widespread closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, that figure dropped to almost 130,000 workers. As of May this year, service industry employee numbers had climbed back to more than 200,000.

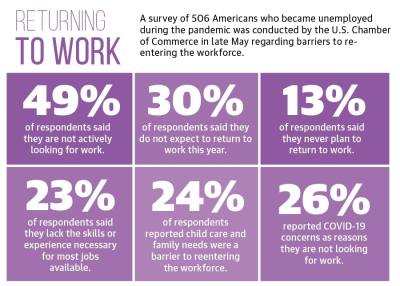

Still, many local restaurants say it is difficult to find workers. Plano Chamber of Commerce President Kelle Marsalis believes a combination of factors is behind the worker shortage.

“It’s not only finding individuals but finding the right talent and getting the right occupation,” Marsalis said. “And then there’s all these other things that have been interrupted due to COVID.”

For some Plano residents, Marsalis said trouble finding child care and reliable transportation as well as the rising cost of housing are affecting the return to work. Even before the pandemic, she said, many service industry employers in Plano often hired workers who lived in areas with more affordable housing options.

Marsalis said the prevalence of remote work may be more appealing than returning to a restaurant.

“If you are somebody that was in the service industry but can also do some other things,” Marsalis said, “that work-from-home option could be pulling them away from going back to an in-person position.”

Switching careers

Richardson resident Siraham Lerma spent 20 years working in various bars and restaurants in the Dallas area. Lerma said he never thought of doing anything else and had planned to open his own bar one day.

While on furlough during the pandemic, Lerma said most of his coworkers were making nearly as much in unemployment payments as they were when they were working. Lerma said he decided not to file for unemployment and was eager to return to the bar where he worked.

“I was the first one to come back and the only one for a while,” Lerma said. “Because nobody wanted to come back.”

Tired from the long hours and looking for a lifestyle change, Lerma said his girlfriend convinced him to look at other jobs. At first, Lerma said he wasn’t sure he was qualified for anything else. But he soon landed a remote job for Geico selling insurance.

“I really did love the service industry,” he said. “But this career change has been really positive for me. My girlfriend makes fun of me because ... I roll out of bed, have my coffee, walk the dog and then I’m just in my office, working from home. I love it.”

Karen Musa, executive dean at Collin College with an extensive background in hospitality and food service management, said restaurants being forced to shut down or transition to different service models caused financial stress for employees.

As businesses reopened with restrictions, employees who relied on tips weren’t making what they used to, said Musa, who helps oversee the Institute of Hospitality and Culinary Education at the college.

“A lot of people did move on because they had to support their families,” Musa said. “So, even as it started coming back, they gravitated to another industry, which may be less volatile.”

The combination of customers dining out more often and less experienced restaurant employees may be contributing to a perceived staffing shortage, Musa said.

“The public ... is wanting to get back to normal,” Musa said. “But a lot of [restaurants] are not ready for that.”

She said that it is the perfect time for younger, less experienced workers to enter the field as many more tenured workers have changed jobs.

“It’s very entry level ... You can learn some great skill sets in this industry,” Musa said. “How to interact with people, how to read people, customer service, time management, organizational skills. And you can take those skill sets and apply them in many other areas.”

Considering unemployment

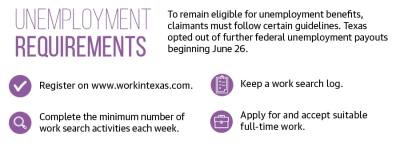

Gov. Greg Abbott announced in May that Texas would opt out of further federal unemployment payouts related to COVID-19 as of June 26, citing an abundance of jobs as well as fraudulent unemployment claims. This included the loss of a weekly $300 supplemental benefit, a move that some said helped push people back to work.

In Plano, the number of residents receiving unemployment benefits peaked at nearly 18,000 in April 2020, a reported record-high for the city, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Those numbers are closer to 7,000 as of May, still a few thousand higher than 2019 numbers.

Jonathan Lewis, senior policy analyst with Every Texan, a nonprofit that advocates to improve equity in health care, education and jobs, said blaming workers’ benefits implies that unemployed Texans are unwilling to work.

Lewis said he believes factors such as child care, low wages and a lack of jobs that match an employee’s skills can turn away potential workers.

“This characterization that workers are lazy is pretty damning,” he said. “If it’s just a $300 benefit that’s holding people back from accepting a job, [it’s] a pretty sad state of affairs.”

Another issue facing some workers is that some salaries are not high enough to afford the basics.

In Collin County, the average family of four needs to bring in $6,783 a month after taxes, or about $81,400 annually, to afford housing, food, transportation, health care and other necessities, according to Economic Policy Institute.

Putting workers first

Bavarian Grill, an authentic German restaurant that has been in Plano for 27 years, is built around its in-person dining experience, owner Juergen Mahneke said.

Mahneke said he was unsure his restaurant would survive the pandemic. Through it all, Mahneke kept his employees paid.

“We were able to hand them a paycheck, as if they had worked,” Mahneke said. “A lot of folks were really very appreciative of that.”

Mahneke said he used his own money and two separate Paycheck Protection Program loans to pay his staff of more than 30 workers until his business could reopen safely.

Even still, Mahneke said three employees quit after a month of the restaurant being closed. Bavarian Grill typically has 15 servers, but at one point, Mahneke said he had four.

It took months of posting ads as well as interviewing and training employees with less experience, but front-of-house manager Cameron Bentley said, as of late July, the restaurant was fully staffed. He said workers who stayed forged a strong bond throughout the uncertain months of the pandemic.

“This is the strongest staff I’ve had in terms of camaraderie, teamwork and reliability,” Bentley said. “They all stuck it out, and we stuck it out. There’s no book to read ... [on] how to keep and maintain staff during a pandemic.”

According to Mahneke, Bavarian Grill is making nearly as much as it did before being forced to close, in large part due to its dependable staff. He said when it comes to keeping and retaining quality workers, restaurant owners must follow the “golden rule.”

“Make sure they have the financial ability to stay afloat,” he said. “I mean, that's the main reason why they come here in the first place.”

Emily Jaroszewski & Anna Lotz contributed to this report.