“Our plan completely changed,” Elsayed said. “In the beginning, it was a challenge.”

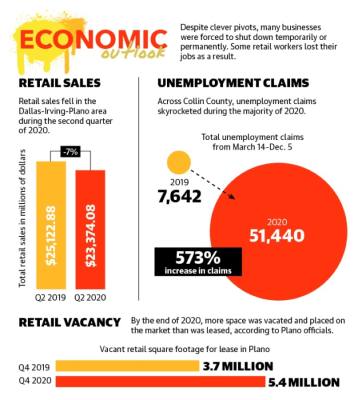

COVID-19 caused “the biggest disruption of retail” the Dallas-Fort Worth market has seen in the last 30 years, said Bob Young, executive director of real estate services firm Weitzman, during a Jan. 14 event. In Plano, about 5.4 million square feet of retail space was vacant at the end of 2020 compared to 3.7 million square feet a year prior.

Despite these challenges, many small businesses pivoted to make ends meet. These innovations kept sales going during a time when many customers opted to stay at home, said Kelle Marsalis, president and CEO of the Plano Chamber of Commerce.

“Pre-pandemic, [retail] was a huge part of our local economy, and it has been through the pandemic,” she said. “I think it will always be a major part of our local economy.”

A tale of two industries

Plano is a hot spot for retail, Marsalis said, which may explain why even though leasing numbers were down, sales for some businesses remained steady. Much of this probably has to do with a surge in e-commerce, she said.

“This was a little bit of ‘the tale of two industries,’” she said. “Some large retailers and national retailers are having some of the best years they’ve had. Unfortunately, it’s not the same for small retailers.”

Sharp increases in the number of e-commerce transactions are partly responsible for a boost in statewide retail sales last summer, according to an Aug. 3 report from Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar. Total sales tax revenue in July was $2.98 billion, a 4.3% increase over July 2019, Hegar said.

After four months of year-over-year decreases, sales tax collections in Plano picked up slightly in August.

Small businesses had a harder time pivoting to digital. Meagan Wauters, owner of Lyla’s: Clothing, Decor and More, said she was successful in moving almost all of her products online but was unable to compete with e-commerce juggernauts, such as Amazon.

“We are still predominantly an in-store shopping business,” she said.

Alex Plotkin, senior business advisor with the Collin Small Business Development Center, said Wauters’ experience is common for many small retailers.

“You can’t open an online version of a store and hope people show up,” he said. “There is no drive-by traffic online, so you don’t even have the benefit of that.”

This made digital marketing during the pandemic more important than ever, Plotkin said. The chamber and the Collin SBDC saw surges in requests from clients and members for guidance on how to market themselves online.

“During COVID, e-commerce became a lifeline,” Plotkin said. “So [businesses] needed to learn how to optimize that channel.”

Elsayed said he invested a lot of money into building a digital presence for Nerfies. He thinks these efforts will pay off once people feel more comfortable gathering, he said.

“[People are] talking to each other in the comments and saying, ‘Hey, let’s do that when things cool off,’” he said.

Innovations born of the pandemic

In addition to promoting themselves online, many business owners began offering new products and services in hopes of attracting customers.

After weeks of little to no foot traffic, June Parker said she was desperate to get customers through the door at her business, Pipe & Palette, which offers in-person art events and parties. Out of that desperation came The Splatter Room, a closet Parker converted into a space where small groups create splatter paintings.

Word about the The Splatter Room traveled quickly, and after Parker was featured on a popular blog and a TV news program, sales surged.

“We were trending on TikTok and had more business than we could imagine,” she said.

While most pivots were not as successful as Parker’s Splatter Room, they were effective enough in pulling retailers—particularly those with a healthy base of capital—through the crisis, Plotkin said.

“It’s a survival technique, ... [the success of which] depended a little bit on what you had to start with,” he said.

However, some businesses were not built to pivot. Maria Rourke, owner of Roosters Men’s Grooming Center in Plano, said she and her husband had no choice but to absorb the revenue lost over their nearly three-month closure.

A year later, clients have returned to Roosters, but the Rourkes are now saddled with new expenses.

“We had to put a lot of money into other things we hadn’t thought of before, like disinfectants, gloves and masks,” she said. “So that hurt a bit.”

The future of retail

This crisis has unlocked new consumer behaviors that are not going away any time soon, Marsalis said. Rather than trying to beat e-commerce giants, Marsalis said, small businesses may benefit from partnering with them.

“Sometimes, we have to learn how to work with instead of against some of these challenges,” she said.

The city has also organized efforts to support small businesses, Marsalis said. The Shop Plano First campaign, for example, encourages residents to keep their tax dollars in Plano by patronizing local retailers.

“Our small retailers have really taken a risk ... to really shift their whole business model to support the community and the residents and the shoppers,” she said. “So let’s support them back; let’s choose them before we choose others."