The League City Police Department in April used genealogy technology to make a breakthrough in a decades-old cold case, bringing answers to the community and closure to families.

But the work in bringing justice to the victims is not over, and police will not stop now, Chief Gary Ratliff said.

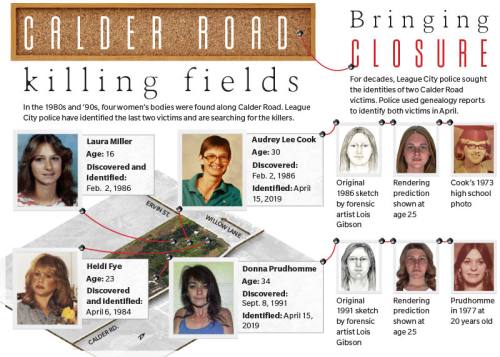

In mid-1980s and early ‘90s, police found the bodies of two unidentified women, Jane and Janet Doe, in a field in the southwest quadrant of the Calder Road intersection with Ervin Street. Previously, two other women’s bodies had been discovered in the area that has come to be known as the Calder Road killing fields.

In April, after years of work, League City police identified both women.

Ratliff, who was working as a patrol officer the day Jane Doe was found, has refused to let the cold cases go, allowing police to identify the victims. Now police are piecing together the lives of the two victims, Audrey Lee Cook and Donna Prudhomme, in hopes of catching the killer or killers.

“The reason that we never stop is because we always hope we’ll have the opportunity to bring closure to the family and justice to the victims,” Ratliff said.

COMMUNITY SHOCK

In April 1984, police found the body of Heidi Fye, who had been missing since October 1983, in the fields near Calder Road and Ervin Street after a family dog brought partial skeletal remains to a home on Ervin Street. In September 1984, Laura Miller was reported missing, and her body was found in the same area by two bicycling boys Feb. 6, 1986. Both women were quickly identified.

However, on the same day as Miller’s discovery, police also found nearby the body of an unidentified Jane Doe. On Sept. 8, 1991, two people riding horses in the fields found the body of another unidentified woman, Janet Doe.

Both women would remain unidentified for decades.

Ratliff said he remembers the day Jane Doe, later identified as Audrey Lee Cook, was found. As he has remained with the League City Police Department and worked his way up, he has refused to let the Calder Road killings go.

“It’s always bothered me that we had these victims that we’ve never been able to provide justice for,” Ratliff said.

Mayor Pat Hallisey was a League City resident when the women’s bodies were found. For what was, at the time, a relatively quiet small city, the deaths were a shock to the community, he said.

“When all this was happening, it was a big deal,” he said. “Anybody that had children was certainly keeping them close.”

There are several reasons that could explain why four bodies were found in the Calder Road killing fields. One is that a serial killer was responsible for all four deaths and used the same area to dispose of the bodies, police said.

Ratliff pointed out most murders are linked to different killers rather than a single person.

“The majority of these cases are individual cases,” he said.

Another explanation is the area where the fields are today was largely quiet and empty in the 1980s and ‘90s, Lt. Michael Buffington said.

“It was an unpopulated area. It was a convenient area where there was not a lot of potential to run into other people,” Buffington said.

Also, League City is about halfway between Houston and Galveston, making it an ideal midway point to dispose of bodies, Detective Gina Vogel said.

“Really the only thing we are absolutely sure of is the dumping site of the bodies is the same,” Buffington said. “Everybody’s got a working theory on it. The prudent thing to say is anything is possible.”

Whatever the reason, League City police are still looking for answers, and a breakthrough happened when they identified Jane and Janet Doe.

DECADESLONG INVESTIGATION

Cold cases cycle through different League City detectives as people are promoted, retire, make lateral transfers and otherwise shift throughout the League City Police Department. The cases of Jane and Janet Doe were no different, Ratliff said.

“This case has passed on from detective to detective throughout the years,” Ratliff said.

League City detectives have tried different methods to identify the women. One was a nationwide campaign of billboards in hopes someone would have information on the victims. Another was to reconstruct their skulls with clay based on police sketches.

“We’ve taken multiple steps and try to put that out each time, but it wasn’t until [Buffington and Vogel] were introduced to newer technology that we were able to step in to where we’re at today,” Ratliff said.

Vogel learned of a company called Parabon Nano Labs that can take DNA and make 3D renderings of what people might look like at certain ages. In addition, the company could determine the victims’ eye and hair colors and other details police did not know, Vogel said.

After getting the funding, it took a long time and a lot of back-and-forth work to get viable DNA of both victims to Parabon, which eventually released 3D renderings of both women’s faces.

“That process took a year,” Vogel said. “It’s a very long process.”

Parabon then introduced League City police to genetic genealogy technology, which was just emerging at the time. Parabon took Jane and Janet Doe on as trial cases, and the company used their DNA to identify their great, great, great grandparents and that Jane Doe was from Tennessee and Janet Doe was from Louisiana, Vogel said.

Using DNA data, detectives started piecing together incomplete family trees. They used genealogy database GENmatch to help fill in the gaps and looked at surnames to build complete trees, Vogel and Buffington said.

Building the trees was a trial-and-error process. Detectives sometimes followed a branch thinking at the end they would find the identities of Jane and Janet Doe only to realize they had gone down the wrong path and would have to restart, they said.

After months of work, detectives determined the victims’ maternal and paternal surnames and knew they were close.

“Once you can whittle it down to that, then you start reaching out to those family members and start getting DNA,” Vogel said.

Almost everyone League City police contacted for DNA samples to see if they were related to the victims was cooperative.

“Everybody wanted to help out,” Buffington said.

Eventually they called relatives who said they thought they knew the victims. Buffington had called media outlets in Tennessee to see if anyone knew Jane Doe, and ultimately her aunt called in to confirm her identify.

Detectives had identified the victims, and DNA tests compared to living relatives proved it.

“Some days you think you’re never gonna get there. It really happened so fast,” Vogel said. “It still gives me goosebumps.”

Hallisey said police’s tenacity gives residents peace of mind.

“I think it gives comfort to every parent or every person in town to know that no matter what happens our police department does not stop until they find a solution of one type or another,” he said.

SEARCH FOR JUSTICE

Despite identifying all four women, the League City police’s work is far from over.

Detectives are trying to work through both Cook’s and Prudhomme’s pasts and whittle them down to the women’s final weeks and days.

“We need to funnel it down to who saw them last,” Buffington said. “It’s tough.”

Police have conducted 60-70 interviews since the women were identified. Some of these interviews are being done out of state, including Alabama, Colorado and California, Buffington said. Many people alive and near League City during the murders are no longer around, making the process harder, Vogel said.

“We got our work cut out for us,” Buffington said.

So far, police said they discovered Cook moved to the Inner Loop of Houston with her girlfriend in 1980. Her girlfriend eventually moved out of state. Cook likely got involved with drugs and stayed in contact with her mother through occasional letters and calls up until her death.

Prudhomme grew up in Port Arthur and eventually moved to Austin with her two sons after a falling out with her husband. She eventually took her sons to live with their grandparents and moved to Seabrook up until her death.

It is not much to go on, but Ratliff and his detectives will not give up on the case and the search for justice for both women, they said.

“I’m surprised by the work these guys do every day,” Buffington said. “I’m very optimistic that we’ll solve it.”