On Jan. 16, the Austin Public Health Department confirmed the city’s first case of rubella since 1999. That news came on the heels of the health department clearing Austin’s first measles case in the same time period that was announced in December.

Both of those diseases are preventable by the mumps, measles and rubella vaccine, which is required for Texas children enrolling in school. But nonmedical exemptions from those vaccinations—allowable by state law—have been filed at increasing rates over the past decade in Austin and its surrounding cities.

That leaves Austin vulnerable to an outbreak of even more cases of vaccine-preventable diseases, local health care experts said.

“The measles case and recent rubella case were, luckily, just one person [each.] ... There is no guarantee the next case will be just one person,” said Dr. Elizabeth Knapp, the co-chief of pediatrics at Austin Regional Clinic.

Disease resurgence

On Dec. 21, APH announced it had confirmed the city’s first case of measles in two decades. The infected individual, a man who had traveled abroad, had visited a handful of locations in Austin, including three restaurants and a Target in Northwest Austin, causing the general public to be at risk of contracting the highly contagious disease.

APH was able to close the possibility of an outbreak of measles related to that case. Two weeks later, however, a case of rubella was confirmed in a separate individual.

Last spring, a team of medical researchers predicted these cases may happen in Travis County.

Medical journal “The Lancet Infectious Diseases” in May published a study that found Travis County was one of 25 counties nationwide with the highest risk for a measles outbreak.

“More and more people have been choosing to opt out [of vaccines]. ... Not coincidentally we’re seeing outbreaks of disease,” said Allison Winnike, the president and CEO of the Immunization Partnership, a Texas-based nonprofit that aims to eradicate vaccine-preventable diseases.

Travis and Williamson counties have both seen the rate of students with nonmedical exemptions from immunizations rise since the 2010-11 school year, up to 2.42% and 2.33% in the 2018-19 school year, respectively. The state average in the 2018-19 school year stood at 1.2%.

Private schools, in particular, have the highest nonmedical exemption rates in the area, according to state data.

"We're very lucky it was an individual [measles] case. Our luck is going to run out as these immunization rates continue to drop," said Dr. Renee Higgerson, medical director of inpatient pediatrics and pediatric critical care at St. David's Children's Hospital.

Measles is a highly contagious disease that could, if brought into a small private school community, spread across the entire campus and infect children, said Dr. James S. Hahn, a family medicine practitioner affiliated with health care company MDVIP.

Hahn told Community Impact Newspaper he believes the recent measles and rubella cases in Austin have a high potential to be the first of many.

“It is a possibility that this is the tip of the iceberg,” Hahn stated. “If we see one case, are we waiting on five or 10 cases to appear over the next several months?”

Legal exemptions

Winnike traces the decline in vaccination rates back to 2003 when the 78th Texas Legislature passed a bill allowing exemptions from immunizations for “reasons of conscience.” Previous to that law, students were only allowed exemptions for medical or religious reasons.

In the 2018-19 school year, Austin ISD, Pflugerville ISD and Round Rock ISD hit decade highs in conscientious exemption rates, state data shows.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 45 states and Washington, D.C., grant exemptions from immunizations for religious reasons, and 15 states allow for philosophical exemptions.

California, Maine, Mississippi, New York and West Virginia allow only medical exemptions.

New York changed its state law after a measles outbreak that began Oct. 1, 2018, lasted almost a full calendar year and infected 406 individuals, according to numbers from the New York State Department of Health.

California in 2015 removed exemptions based on personal beliefs after a measles outbreak that began at Disneyland infected 147 people across seven states, Mexico and Canada, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Several attempts to roll back nonmedical exemptions to vaccines have died in the Texas Legislature. Bills were proposed in 2017 and 2019 that would have mandated every public school campus report exemption rates to the state to be made publicly available. Neither measure made it to a chamber for a vote by lawmakers.

“That [2003] law has been very closely defended by the anti-vaccination lobby that got it passed,” Winnike said. “The anti-vaccination lobby in Texas, although they are small in number, are extremely passionate.”

Global problems

It has been two decades since the CDC declared measles eradicated in the U.S., and a half-century since the measles vaccine was first developed.

Local physicians said the distant memory of the devastating health effects of vaccine-preventable diseases may be part of the reason why vaccination rates have slipped.

“Most parents don’t know people who had polio or measles,” Knapp said. “They have forgotten the one thing we did in the last 50 years that has protected us is vaccination.”

Some measles cases can lead to fatal brain infections later in life, Knapp said.

Pregnant women who contract rubella are at risk for miscarriage, and the developing fetuses are at risk of developing birth defects with lifelong consequences, according to the CDC.

The World Health Organization listed vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019, alongside threats such as climate change, ebola and an influenza epidemic. More than 10,000 deaths were attributed to pneumonia and influenza in the Texas 2018-19 flu season.

As immunization rates dip globally, local populations are more at risk of contracting vaccine-preventable diseases, especially as Austin attracts more visitors. More than 45,000 international travelers passed through Austin-Bergstrom International Airport in October, an 18.38% year-over-year increase, according to numbers from the airport.

“We're highly at risk for any infectious diseases because of our global travel. ... You add the high rate of unvaccinated people and that makes a perfect set up [for an outbreak,]" Higgerson said.

It will be more than one year before the next time exemption laws can be addressed at the state level, and Winnike said cities and counties cannot pass their own vaccine policies.

Until then, Knapp said it is important for the local community—including private school institutions, parents and unvaccinated adults—to keep vaccination coverage high to prevent future outbreaks.

The University of Texas at Austin announced this January that beginning in the fall, all incoming students must be vaccinated against measles.

“We want to make sure we are giving safety to those who are too young to receive vaccination or may have an illness that prohibits them from getting vaccinations,” Knapp said.

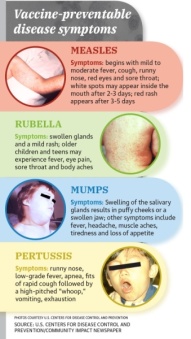

Note from the editor: A previous version of this story listed the same symptoms for mumps and rubella in the graphics. This mistake has been corrected.