Williamson County Emergency Medical Services deployed Narcan to 63 county buildings from Nov. 2-10. The lifesaving medication can now be found alongside automated external defibrillators at these facilities.

“Our desire is to make Narcan more publicly available [and] to make people aware of the danger of the opioid overdoses,” said Amy Jarosek, WCEMS community health paramedic program lead.

This initiative comes at a time when law enforcement seizures of pills containing illicit fentanyl increased nationwide by 3,224% between January 2018 and December 2021, according to the National Institute of Drug Abuse. In 2018, law enforcement seized 290,304 pills containing fentanyl. That number rose to 9.6 million in 2021, according to the NIDA.

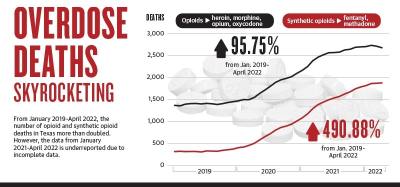

Locally, Jarosek said WCEMS began seeing an increase in opioid-related overdoses around 2019. This was followed by a dip during the height of the pandemic in 2020, but overdose numbers have been rising again.

“We know that our neighborhoods, especially to the north and the south in Bell County and in Travis County, have seen an increase in their opioid overdoses,” Jarosek said. “We have seen an increase, certainly not as steep as they’ve seen south and north of here, but we know that if those things are occurring in our neighboring counties, they are certainly going to come into our county as well, so we wanted to get ahead of that.”

Harm reduction

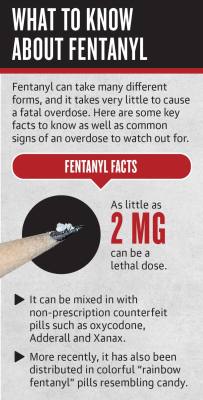

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid used for pain management, prescribed by doctors for severe pain and advanced-stage cancer, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, the drug has been created illicitly in pill-pressing laboratories.

Fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the CDC. Two milligrams is the lethal dose of the drug, which is a major contributor to fatal and nonfatal overdoses in the U.S.

Local law enforcement officials said fentanyl is often laced into other drugs, which means individuals often do not know fentanyl is in what they are taking.

“Why fentanyl is tricky is because people that are doing drugs, their desire isn’t necessarily to do fentanyl, and they don’t know it’s in what they’re doing,” Georgetown Police Department Chief Cory Tchida said. “They think they’re doing something else, not realizing that they’re also doing fentanyl, and it’s having tragic outcomes. So we are certainly paying attention to it, and we are certainly seeing, compared to five years ago, an uptick in the deaths and [drug] seizures.”

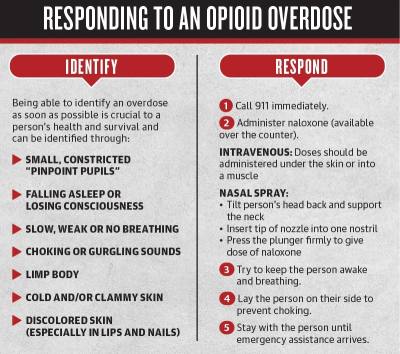

Symptoms of a fentanyl overdose include unconsciousness, vomiting, slow or shallow breathing, pale skin, small pupils, and purple lips and fingernails, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Fentanyl is the No. 1 leading cause of death in people ages 18-45, and 99% of overdoses are accidental, according to the Texas National Guard.

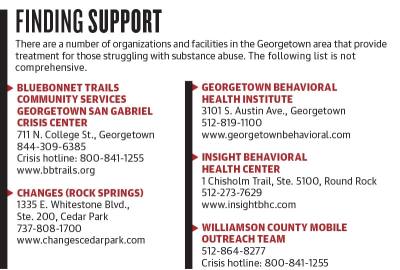

Jarosek said deploying Narcan into county facilities is the first phase in a tiered harm-reduction collaboration between WCEMS and Bluebonnet Trails Community Services—an organization that provides health care services, including those for mental health and substance use—which provides the Narcan.

By putting Narcan in a public space, Jarosek said WCEMS hopes to reduce the stigma surrounding getting help. She said the medication—a nasal spray—is easy and safe to administer, and if given to someone not experiencing an overdose, will not cause any harm.

Furthermore, WCEMS uses the PulsPoint app, which community members can download. Using 911 live call data, the app alerts users of potential instances of cardiac arrest if they are nearby. That person is also given information on nearby AEDs and Narcan.

“Bystanders can be on the scene several minutes before first responders, and for somebody that's not breathing as a result of an opioid overdose, those seven minutes can make a difference between life and death,” said Jim Persons, WCEMS public education department head.

Protecting the community

Tchida said the GPD has used Narcan more than the department ever anticipated it would.

Now, every sworn officer with the GDP is issued with doses of Narcan. The medication has become prevalent enough that companies have created holsters for officers to carry doses on their belts.

Tchida said Georgetown has had a handful of overdose deaths over the last few years the department attributes to fentanyl, with officers encountering the drug more often, typically among younger people.

“The good thing is it definitely is saving lives,” he said.

The next phases of the WCEMS’ Narcan rollout plan is to make sure smaller first responder agencies throughout the county have access to the medication, Jarosek said.

Then, the WCEMS hopes to put Narcan in public pacing locations and be an education resource for school districts in the community. Jarosek said these conversations with the districts have not yet started.

“My hope is that we can ensure the schools have the Narcan that they need and that they desire to have while staying within their governance,” Jarosek said. “I think the interest is there, we just need to find out what they need and want from us before we go about that.”

Educating students and parents

The possibility of fentanyl finding its way onto GISD campuses was already on the district’s radar prior to this year.

In 2021, GISD supplied its secondary schools with four doses of Narcan in the event of an overdose. After the death of four students in Hays CISD, the district bumped the number of doses up to six per secondary school and implemented two doses for each of the elementary schools.

“In our experience, it hadn’t really hit us,” said Heather Stoner, executive director for student and campus services. “Then you had multiple students dying in a nearby school district, which is still a couple districts away but still close enough that we can’t just sit by and not try to do something proactive.”

The first thing the district did was get with its high school principals to discuss ways to educate parents about the risks associated with prescription drugs and the dangers of fentanyl. Officials crafted information about signs to look for, the symptoms of the drug, how children could come in contact with fentanyl and more.

The district is in the process of setting up a partnership with the Williamson County Sheriff’s Office and its narcotics division to provide officials with training specific to fentanyl and incorporate lessons through health classes.

Also, GISD will host a presentation Jan. 9 with a speaker who has been directly involved with fentanyl cases in Travis County addressing the community about what to watch out for.

“It’s kind of a collaboration between the district and PTA to bring as many parents out so we can make them aware of what’s going on with not just fentanyl, but substance abuse in general,” said Mindy Petty, GISD coordinator of health services.

Zara Flores and Zacharia Washington contributed to this report.