Increasingly worried he might die of hypothermia, Crowder, 73, set down his book and began pacing his Southeast Austin apartment to maintain his body temperature. He called his son, who said he could hear how cold his dad was in the sound of his voice. His son had electricity but was 22 miles away in North Austin. Out of options and alone, Crowder climbed into his two-wheel drive Toyota Highlander and hit the icy roads, knowing full well he might not make it.

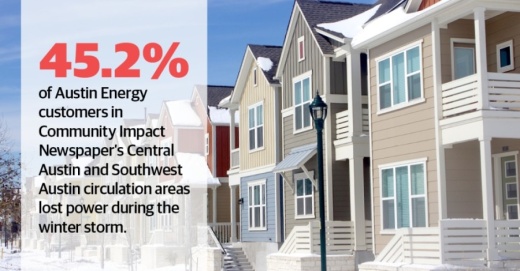

Crowder was one of millions of Texans, and 220,000 Austinites, who lost power during the historic arctic blast that plunged Texas into prolonged subfreezing temperatures and knocked out nearly half the state’s power supply for days. The electricity crisis then cascaded into a water crisis. In Austin, the frozen temperatures burst tens of thousands of pipes and water mains and the city’s 100-million-gallon water reserves spilled into homes, apartment complexes and streets. For days, two-thirds of the 11th largest city in the U.S. had no running water. Those who did had to boil it before consuming. Even in mid-March, more than a month after the storm, some apartment tenants were still dealing with spotty outages, dirty water and damage to pipes, according to Shoshana Krieger, project director at tenants rights nonprofit Building and Strengthening Tenant Action.

Crowder, who has spent most of his life in Texas, learned, just like many others that week, his home state is the only state in the U.S. that operates on its own electric power system, untouched by federal regulation. He learned that power system is run by a nonprofit agency, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, and that the agency miscalculated how severely the storm would impact electricity generation and demand. He learned the deregulation of the state’s electricity system meant power generators were not required to reinforce themselves against extreme weather events.

“I think the state of Texas ought to forget about having our own power supply and going it alone,” Crowder said. “It’s apparent that the systems in place are not adequate.”

Crowder also learned that millions of Texans left freezing without electricity for days, some dying, was an option chosen by ERCOT executives in the early hours of Feb. 15 because the alternative would have carried greater consequence—a complete failure of the state’s power system that would have left 26 million Texans without electricity for weeks or longer. Resignations have been swift, as has finger pointing. Legislators have called for sweeping changes. The governor has called for tighter regulation. Across the state, investigations have been launched into figuring out how the state power system got to a point where executives had to choose between a couple million suffering for days or 26 million suffering for weeks.

“[The] legislative session will not end until we fix these problems,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said.

Four minutes and 37 seconds

The Texas power system runs on a relationship between electricity production from its power plants and electricity demand from its utilities and their customers. The balance between supply and demand is measured in frequency, or the pulse of the system. A healthy pulse, according to former ERCOT CEO Bill Magness, is 60 hertz. ERCOT’s job is to facilitate electricity from power plants to utilities and maintain that healthy pulse. An imbalance between supply and demand is harmful, and power plants are programmed to switch off when demand begins to dramatically outstrip supply.The icy temperatures that hit the state in the early hours of Feb. 15 caused issues at unprepared plants. Natural gas and coal plant equipment malfunctioned; wind turbines froze; and snow smothered solar panels. Supply across the state slowed as demand from utilities—their customers cranking the heat—skyrocketed. An imbalance was underway, leading power plants across the state to switch off, further plunging electricity production. At around 1:23 a.m., the system’s pulse dropped below 60 hertz.

ERCOT, over the next 28 minutes, told utilities to begin essentially unplugging some customers to balance demand with limited supply. However, power plant outages continued. At 1:51 a.m., the pulse dipped below 59.4 hertz. Magness said if the system stayed below 59.4 hertz for more than 9 minutes, more power plants would trip off and the system would fail, sending 26 million Texans into a weekslong blackout. ERCOT ordered utilities across the state to unplug as many customers as possible—an unprecedented command. At about 1:55 a.m., with 4 minutes and 37 seconds left, the pulse rose above 59.4 hertz.

A statewide blackout was averted, but millions were now left without power in record-freezing temperatures.

The vulnerability of deregulation

Around the same time, Crowder received a text message from Austin Energy that he was one of the many customers whose power was shut off.

Around the same time, Crowder received a text message from Austin Energy that he was one of the many customers whose power was shut off.Less than 12 hours later, unsure the power was coming back, Crowder embarked on his journey to his son’s house. He guessed I-35, less than 2 miles away, would be a relatively clear and flat path; however, he underestimated the hills on his neighborhood streets. He said he was only 200 feet from his apartment before he saw his first accident and screaming match between drivers.

“It was slow-motion chaos,” Crowder said.

He pushed on, slowly sliding through empty intersections and failing, several times, to make it up the hills between him and I-35. After nearly an hour of driving, Crowder was ready to give up when he saw a four-wheel-drive truck heading his direction. Crowder moved into its wake and was able to trail it up the hills and on to I-35.

Although initially advertised as a rotating blackout, state and local energy officials said the prolonged freezing temperatures kept electricity production down. Austin spent a record 162 consecutive hours at or below freezing. Dangerous road conditions across the state made it difficult for crews to reach power plants for emergency repairs. It took days for equipment to thaw out. The supply taken out by the storms was so severe—48% of the state’s total electricity supply—that, for days, Austin Energy only received enough energy from ERCOT to power its most critical infrastructure. There was not enough electricity to rotate.

Officials blamed a failure of modeling and regulation. Austin Energy General Manager Jacqueline Sargent said ERCOT’s planned worst-case scenario was blindsided by the severity of the winter storm and that planning and modeling needed to be adjusted.

“As we continue to experience hotter summers and colder winters, I think we are going to need to consider some extreme cases because what we saw went well beyond anything in the [forecasts] that came out for this winter season,” Sargent said.

Sally Talberg, former chair of the ERCOT board of directors, said all weather models across electricity systems needed to be “recalibrated” to account for extremes beyond the storm.

Unlike power suppliers on the national grid, plants in ERCOT’s system are not required to reinforce themselves against extremes. Magness said ERCOT “spot checks” about 80 of 680 power plants per year but can only make weatherization recommendations.

Kaleb Todd, a member of the Austin chapter of the Sunrise Movement, a national organization that pushes for action on climate change, said requiring the state’s energy infrastructure to be weatherized is crucial in building a grid that can stand up to climate change. Abbott has agreed. Abbott named mandating and funding the “winterization and stabilization” of the state’s power system a “legislative priority.”

The fallout

Crowder made it safely to his son’s house Feb. 15; however, soon after he arrived, they also lost power. Crowder would have to travel one more mile to a friend’s house, where he stayed until Feb. 22. It was the first socializing he had done during the pandemic.

Crowder made it safely to his son’s house Feb. 15; however, soon after he arrived, they also lost power. Crowder would have to travel one more mile to a friend’s house, where he stayed until Feb. 22. It was the first socializing he had done during the pandemic.“I hope political heads will roll when this is over,” Crowder remembers thinking.

Since the blackouts, eight members of ERCOT’s board have resigned, including Sargent and the chair and vice chair. The remaining board members voted to terminate Magness as CEO, which means nine of 16 positions are vacant.

All three board members of the Public Utility Commission of Texas have also resigned. The three-member, governor-appointed PUC is responsible for oversight of ERCOT. Legislators said the PUC failed to ensure ERCOT was prepared for such an extreme weather event.

During his own legislative questioning, Magness said it would be up to the Legislature to enact the changes and regulations required to avoid future disasters. Although weatherization has been a sticking point, there has been little discussion around connecting Texas to the national grid.

The 87th Texas Legislature’s regular session will end May 31, with the potential for a special summer session. House Speaker Dade Phelan introduced a slate of bills for legislators to take on during the session, including an overhaul of ERCOT, the winterization of the power system and the creation of a statewide emergency alert system.

“It’s apparent that the systems in place were not adequate,” Crowder said. “If this doesn’t result in massive change in political leadership, then I’m not optimistic about the future of the state.”