Typically, it takes 12-18 months to develop a new vaccine, according to Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. But vaccine researchers—including some in Austin—wasted no time, kicking into high gear in January, before the coronavirus ever reached the United States.

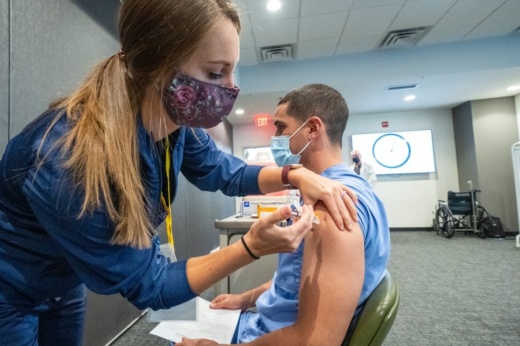

By November, pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and Moderna announced they had produced vaccines with efficacy rates around 95% in clinical trials. After the Food and Drug Administration approved the Pfizer vaccine for emergency use authorization, Texas made its first shipment of more than 224,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine starting Dec. 14. The FDA followed with emergency use authorization of the Moderna vaccine Dec. 18, and Texas sent another 620,400 doses for health care providers across the state beginning Dec. 21. The Moderna vaccine made up about three-quarters of the second shipment.

Hospitals, clinics and pharmacies in Travis, Hays and Williamson counties received 42,000 of those doses for front-line health care workers and nursing home residents. Dr. Mark Escott, the Austin-Travis County interim health authority, expressed optimism in the research reported.

“Not only are we talking about preventing disease spread, we’re talking about—at least, at this stage—completely preventing severe cases,” Escott said.

Years in the making

Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines have a strong local connection: Both use a protein developed in a lab at The University of Texas.Jason McLellan, associate professor of molecular biosciences at UT, sprang into action in early January as soon as the genome sequence was released for the novel coronavirus creating a critical epidemic in China—more than a month before the first reports of COVID-19 in the United States made news. But this was not where McLellan’s work began, his department chair at UT said.

“This is sort of an overnight rapid success that was years in the making. There was a lot of unheralded basic science research that left the scientific community poised to really move fast on a new vaccine,” said Daniel Leahy, the chair of the department of molecular biosciences at UT.

Coronaviruses encompass a large family of respiratory viruses, from the common cold to more serious diseases such as COVID-19. McLellan, along with collaborators at the National Institutes of Health and the Scripps organization, began studying coronaviruses around a decade ago. In 2016, they reported the discovery of a key protein common to coronaviruses, the spike protein, which allows the virus to attack host cells by changing shape.

In the ensuing years, McLellan researched the highly infectious coronaviruses, MERS and SARS. McLellan and his colleagues developed a method to lock the spike protein into its initial shape, promoting the production of antibodies in host cells.

After COVID-19 created an epidemic in China, the McLellan Lab team wanted to be the first to create a basis for the vaccine, but they had no idea the stakes would be so high.

“We were more interested from sort of a basic science standpoint, but within weeks it became clear that the work that we were doing would have much broader implications,” said Daniel Wrapp, a member of McLellan’s lab.

By the spring, the lab began collaborating with Moderna and Pfizer to develop vaccines that were ready to undergo first-round trials. Locally, Austin Regional Clinic helped execute the Pfizer trial. Leahy said nationally, more than 100,000 people tested the vaccine, and according to the FDA, only one individual exhibited severe COVID-19 symptoms.

While the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are the first to arrive in Texas, several others are still in trials. Those vaccines, including one manufactured by AstraZeneca, could be a better fit for rural communities that are hard to reach and do not have ultra-cold storage technology.

Phased rollout

The 42,000 Central Texans who were able to receive a vaccine dose in December will need a second dose. For Pfizer, the second shot will come 21 days later. For Moderna, it will be 28 days later.As the vaccine supply increases, health officials will offer it to people at risk of severe illness from the virus, including those over the age of 65 and various essential workers who are not able to work from home.••As vulnerable populations begin to be immunized, it will take time to see a difference in transmission in the wider community, but hospitals should start to see fewer severe coronavirus cases, according to Spencer Fox, the associate director of the UT COVID-19 Modeling Consortium.

“It’s likely that it will reduce the severity of disease we see but not necessarily likely to slow the transmission much in our region,” Fox said. “But it will help to dramatically reduce necessary health care usage, like hospital beds and [intensive care unit] beds, and also mortality overall.”

Between January and July, Escott said most people will be able to be vaccinated, with healthy, low-risk individuals coming later. Children will likely be last in line, as clinical trials are still being conducted and they are also among the lowest-risk groups. Health officials have said the vaccine will be free for recipients, whether they have insurance or not.

Abbott’s statewide plan stated the vaccine is voluntary, but all the health experts Community Impact Newspaper spoke to recommended vaccination and agreed the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are safe. Reported side effects have predominantly been mild, similar to what one might see from a flu shot.

“I’ll be first in line to take the vaccine when it becomes available. I will encourage my family and everybody I know to get vaccinated,” Leahy said.

Once the general public is offered access to the vaccine, it should not be hard to find. Within Austin Public Health’s jurisdiction, over 150 hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and other providers have already signed up to be vaccine administrators—including major pharmacy and grocery chains such as H-E-B, Walgreens and CVS. When the second shipment of vaccines was sent out Dec. 21, recipients in Central Austin included H-E-B locations on Burnet Road, East Seventh Street and South Congress Avenue. Following health care workers and nursing home residents, people over the age of 65 and those with high-risk health conditions will be next in line.

Seeing a change

As more people take the vaccine, the country will move closer to herd immunity—the threshold of vaccinations at which an entire population is protected from a disease—but it will likely be months before that happens, Fox said.“Experts generally agree that we’ll need somewhere between 50% and 70% of the population immune before we will reach herd immunity and see the slowing of transmission and kind of get back to life as normal,” Fox said.

Although the vaccine will protect those immunized from developing COVID-19 symptoms, the health community is unsure if these individuals will still be able to transmit the virus.

“If it does prevent the individual vaccinated from spreading the disease even if they are exposed, then we’re talking about a timeline of returning to normalcy and having a big bonfire for the masks much sooner,” Escott said Dec. 4.

With coronavirus case counts rising, Travis County is approaching Stage 5 COVID-19 risk, a designation that would likely come with a curfew and heightened business restrictions. As the community waits for widespread access to a vaccine, officials are urging the same cautious behavior they have all along: masking, staying home when possible, social distancing and hand-washing.