"I think the biggest thing I’ve taken from this job is if we want to really look into housing stability, part of that is we need to make sure there’s some sort of social safety net," Chu said.

The tenants whose names were written on those eviction case files did not have that safety net, and every Monday, there was a stack of about 20 more waiting for Chu, he said.

However, the Precinct 5 justice, who hears cases from Central Austin, actually heard the fewest eviction cases in 2020 among his colleagues.

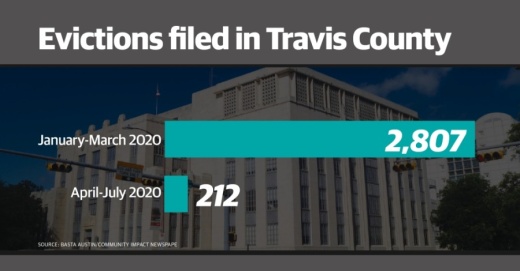

Judge Randall Slagle, whose precinct spans North Austin, heard the most such cases of any Travis County justice of the peace, with 988 filings, according to data compiled by Building and Strengthening Tenant Action, a group that advocates for Austin renters. Travis County Judge Sam Biscoe issued orders on July 22 extending those protections through September 30. Under the new orders, landlords under most circumstances cannot issue a tenant a document called a notice to vacate, which starts the process that leads to a court hearing. Austin has a similar moratorium in place that is set to run through July 25, and District 4 City Council Member Casar said the city is likely to extend its own policy to match up with the county's.

BASTA Project Director Shoshana Krieger said her team is trying to help tenants who are looking for help navigating a confusing patchwork of local, state and federal rules and regulations. She said she is concerned about what will happen whenever the courts open back up.

"We're bracing for a tsunami, a flood of evictions," Krieger said.

Jeannie Nelson, executive director of local nonprofit organization Austin Tenants Council, said the moratorium policies have helped buy renters more time, but without direct financial assistance, such measures simply delay evictions because tenants who have lost their jobs and their incomes during the COVID-19 crisis do not have an ability to catch up after falling behind.

"We haven’t seen any of the fallout from the eviction crisis related to COVID-19 right now," Nelson said.

A new program from the city of Austin hopes to address the root cause of the housing problem instead of simply kicking the can down the road. In August, the city will open applications for the second version of its Relief of Emergency Needs for Tenants program. That will provide $17.75 million—mostly from federal coronavirus relief dollars—to help residents pay their rent.

Mandy DeMayo, community development administrator for the Department of Neighborhood Housing and Community Development, said about 73% of the funds will go toward direct assistance, and the funds will be stretched across six months. "We’re mindful of the fact that somebody who can pay their rent in August might not be able to pay their rent in September and October," DeMayo said.

The city has additional protections in place to help renters, who represent 55% of all city households. From now until Aug. 24, if a renter falls behind on their payments, they have 60 days from the day their landlord delivers a document—a proposal to evict—to catch up on rent before the landlord can actually start the eviction process.

But when jobs disappear, unemployment rates rise and rent is not paid, the pain is not felt only by the tenant. Landlords also suffer financial losses.

In Austin, according to Emily Blair, executive director of the Austin Apartment Association, about 20 cents of every dollar paid to a landlord go to property taxes, and a few missed rent payments can put small property owners in a significant financial hole.

Extending the moratoriums on evictions creates additional uncertainty for property owners, Blair said, and could potentially affect future development, without solving the root cause of the problem— finding money to help renters pay.

"That's why we're continuing to advocate on the federal level, we need to have emergency rental assistance," Blair said. Housing affordability was a major community issue in Austin and around the country long before the coronavirus pandemic. A report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition released in July showed that residents of metropolitan Austin have to make about $26 an hour—3.6 times the minimum wage—to afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rate.

Krieger said she hopes the pandemic has opened some eyes to the issue.

“Evictions are a public health crisis, and they’re entirely man-made,” Krieger said.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect the new orders signed by Travis County Judge Sam Biscoe on July 22.