Her landlord has been flexible, but Khan knows it cannot last. She has had fleeting success subletting her space and creating a digital library of yoga classes along with livestreamed sessions. But none have solved the challenge of paying rent on a 2,000-square-foot studio space that has sat mostly vacant for more than seven months.The entrepreneur in Khan has refused to give in, and she has drawn up one final Hail Mary. With her one-year anniversary around the corner, Khan has reopened Oak + Lotus as a coworking studio. She acknowledged the drastic change but said she is out of options and sees it as the best chance to pay for her space.

“I’m doing what I can because I really don’t want to lose this space. I’ve put so much into creating it, and I see the post-coronavirus potential in it,” Khan said. “The bottom line is, I need to pay the rent. I’m trying to get as creative as possible. How I get paid doesn’t matter. I just need to pay the rent.”

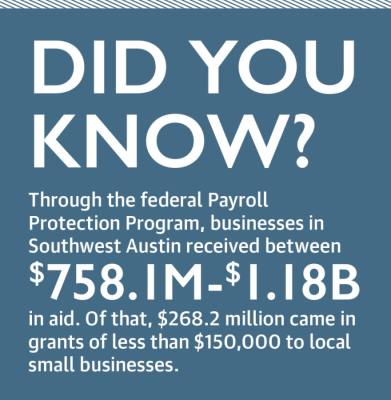

Over more than seven months, this once-in-a-hundred-years public health crisis has ravaged Austin’s famed small-business community, and countless local institutions have shuttered, from Threadgill’s and I Luv Video to Dart Bowl and Magnolia Café. The previously humming local economy has taken a downturn; unemployment reached as high as 12.4%; the city’s live music ecosystem sits on the brink of collapse; and officials say they are not ready for the “tsunami” of hurt once eviction moratoriums expire.

Community Impact Newspaper spoke with 13 small and local business owners and managers across a variety of industries who have, so far, held on. Whether it was a relatively simple switch to virtual or takeout, or a seismic shift in the services they offer, none of the businesses look as they did at the start of March.

Local and federal officials say the coronavirus will likely remain the central community concern well into 2021. The business owners said their minds are shifting from the hectic day-to-day, minute-to-minute reassessments to figuring out how they are going to survive with the pandemic for the foreseeable future.

With consumers spending less, federal stimulus money dried up and local dollars limited, they say their choice is simple, even if the work is not: adapt or lose their livelihood.

Awakening survival instincts

In its own attempt to adapt, Native Hostel and Bar & Café could now be called Native Café, interactive art experience, short-term lease apartment and commercial retail space. With their bar and hostel business stymied by local restrictions and their own comfort levels, co-owners CK Chin and Antonio Madrid had to let go of 90% of their staff. However, they were not ready to give up.

They teamed up with local artists to turn their dormant event room into an interactive art exhibition. They also began leasing out their hostel rooms as short-term residential and commercial space. Current tenants include a chocolatier and a tattoo parlor.

Madrid chalks it up to the “entrepreneurial spirit.” Chin said there are not many options when rent is due.

“I don’t think we have a choice right now whether or not to be open,” Chin said. “It’s hard to gauge whether it’s worth it. ... If this is for three more months then we might be able to tread water but if it’s for two more years then probably not.”

For Movemint Bike Cab, the loss of South By Southwest and spring festival season meant a 50% decline in annual revenue. The hit was near catastrophic but David Knipp, owner of the 12-year-old pedicab outfit, held out hope that if his company could make it until Austin City Limits, it would survive.

As hope for the fall festival season dwindled through the spring and summer, Knipp pursued a new approach. He consolidated his manufacturing warehouse and fleet garage to cut real estate costs and developed a new pedicab design that would shift business from moving people to moving cargo—anything from furniture to groceries and restaurant takeout. Knipp said Movemint is also opening up a bike repair shop and considering selling its building’s front façade as advertising space.

“We’re having to turn on a lot more than just our three-wheeled mind,” Knipp said. “Whether we survive this is a 50-50 toss-up. We’re limited on our funding. Six months from now, I hope we’re still going at it.”

The live events industry has yet to see a revival with no timeline for a return. Lisa Hickey and Autumn Rich, owners of the event production and furniture rental company Panacea Collective, said they had to lay off all but two employees. Typically, the company would do 250 events per year. Since March, Hickey said they have only done 20.

From renting furniture for front yard parties and selling celebration packs with food and furniture to helping people plan virtual events, Hickey said they are trying to bring in business any way possible. The pivot, which Hickey said was like “building a plane while flying” has started to see returns as people have adapted their plans to virtual events and socially distanced gatherings.

“Up until a month ago I would say I was touch-and-go whether we would make it,” Rich said. “But now I’m confident in the way we’ve restructured things.”

An uneven recovery

Local economist Jon Hockenyos, president and founder of the economic consultant firm TXP Inc., said Austin will likely experience a rare, K-shaped recovery out of the pandemic recession, in which some sectors of the economy recover relatively well—the upward facing leg of the K—while other sectors of the economy suffer—the downward facing leg. Local jobs report data shows the financial and manufacturing industries performing well as hospitality, education and health services continue to struggle.

“If your job is mostly managing information, you likely can do your job remotely and are absolutely fine,” Hockenyos said. “If you rely on face-to-face interactions with people, such as in the retail or hospitality sector, you have a long way to go.”

The pandemic pivot is not available to all businesses. Music venues rely on touring acts for revenue. Nearly all of the city’s live music venues have been dormant since March. Cody Cowan, executive director of the Red River Cultural District—a strip in eastern downtown Austin that hosts the densest collection of live music venues in the city—said venues still in business are at one of three stages: preparing to permanently close, exploring bankruptcy or fighting to get food permits in an attempt to bring in some revenue.

Child care facilities have also been limited in their ability to diversify revenue. Pat Smith, owner and executive director of Sweet Briar Child Development Center in South Austin, said the sustainability of her business, which has operated in Austin for decades, is completely at the whim of government assistance. She said the state and federal government have stepped up in a big way to subsidize child care centers; however, she does not know how long it will last.

“I shudder to think how difficult it would be for us to stay open without government help,” said Smith, whose enrollment numbers at Sweet Briar are down to 35%. “I can’t even imagine.”

Austin City Council acknowledged the dire straits facing live music venue and child care facility owners in October, approving a $15 million tax-funded stimulus package mostly aimed at assisting the industries. Austin Mayor Steve Adler said the harm laid on local businesses outweighed local resources and pleaded for state and federal aid.

Without government intervention, Khan said the fate of local businesses lies in the hands of customers.

“If consumers want businesses to still be around when this is over, they need to be willing to support them,” Khan said. “There are people out there who are really trying hard to do that, and it’s awesome to see. But it’s not everyone, and it’s not even close to enough.”