As Central Texans gear up for a third year in the pandemic, many employers are having trouble finding employees due to low unemployment and a lack of skilled workers.

The tight labor market, or the “workers’ economy,” means employees have more power to leave their job for another, ask for higher pay and even unionize, according to local experts.

“Employers in this market are having to be very creative in how they attract and retain talent,” said Tamara Atkinson, CEO of Workforce Solutions Capital Area.

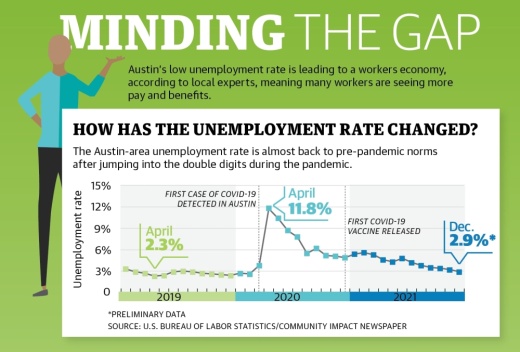

In December, the Austin area unemployment rate was 2.9%, according to Workforce Solutions data, far below pandemic highs of more than 10% and close to the pre-pandemic baseline. At the same time, job growth has exceeded pre-pandemic norms.

“You look at Austin’s [economy], it’s like, if you threw a dart at a map of the United States, it’s the bullseye; it’s as good as it gets,” said Dirk Mateer, University of Texas economics professor.

Mateer and other local experts said Austin’s quick economic recovery from the pandemic is a good thing for many workers.

However, Atkinson said a “skills gap”—a mismatch between the amount of education many of the unemployed workers in the area have and what employers are seeking—is preventing some from seeing the benefits of the economy.

Workers’ economy

Jon Hockenyos, president of Economic Analysis & Public Policy Strategy, an economic consulting firm in Austin, said workers “definitely have the upper hand.”

“You might get a worker in the door at $16 an hour, but you need to be able to offer $20 to keep them,” Hockenyos said.

Ed Still, communication director for Texas American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, said he is seeing an increase in workers looking for higher pay, better benefits and workplace safety.

“We are seeing workers make the choice to leave if the job isn’t right for them or to join up with their fellow workers to demand better treatment,” Still said.

He said that means more people are interested in unions than in the past.

Vance Ginn, the chief economist for Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank based in Austin, said quit-rate data—a measure of the rate at which workers leave their jobs—shows a high rate of people leaving their positions statewide.

“It’s really been more at the lower end where we are seeing people switch jobs more quickly,” Ginn said. “Workers are able to demand higher wages, and employers are willing to pay them.”Jose Vela, who won the special election for Austin’s City Council District 4 in January, said workers’ rights is a key part of his platform.

“When that’s the situation then wages have to go up to get people in the door, and that’s good,” Vela said.

Greg Casar, who stepped down from the District 4 council seat to run for Congress, and Vela both said the benefits of the strong economy are hindered by the rising cost of living.

“We’ve seen an unprecedented spike in housing costs. For a lot of working-class folks, it doesn’t feel a lot different,” Casar said.

Casar said many are struggling with the increasing cost and lack of access to child care, while at the same time feeling less able to rely on public schools, which have moved to virtual or given students extra days off at different times during the pandemic.

He also pointed to transportation and health care costs.

“For many of the folks I’ve talked to, that extra wage increase is getting eaten up by additional costs,” Casar said.

Skills gap

Mateer and other local experts said low skilled employees will need more training to keep up with Austin’s rising cost of living.

“If you’re at the bottom of the economy, because your skill set is such that those are the jobs that you can get, they don’t pay enough to be able to live in Austin any more than they would pay enough to be able to afford to live in Los Angeles, or Chicago, or Houston or Dallas or New York City,” Mateer said. Atkinson said that 70% of individuals unemployed in the Austin area have less than an associate degree. Data shows that 54% of jobs in Texas are considered middle skilled level—requiring more than a high school diploma but less than a four-year degree—and 45% of Texas workers meet those requirements.

Atkinson said Workforce Solutions is focused on helping people navigate barriers to employment and education, including accessing child care and scholarships.

Kevin Brackmeyer, the CEO of Skillpoint Alliance, a nonprofit workforce development organization, said he is seeing a lot of interest both from potential students and employers.

“By providing free and rapid training, we are helping employers close that skills gap and at the same time helping students find higher-paying jobs,” Brackmeyer said.

He said many students are graduating with job offers.

“They’re out there somewhere”

Anthony Zertuche, a plant manager at Austin PreStress, which manufactures construction supplies in East Austin, said his company raised starting pay from $11 to $15.50 an hour, or more with experience.

He said the job is physically demanding and some candidates leave after the first day because they can make the same pay working in fast-food or retail.

“My boss asks me where everyone is at, and I have no answer,” Zertuche said. “They’re out there somewhere.”

Zertuche said the plant has about 27 of the 42 employees it needs. However, he said they cannot afford to keep raising the starting pay if they want to offer competitive prices.

Scott Hentschel, the hospitality partner of Karlin Real Estate and member of the Austin Chamber of Commerce, has recently been trying to hire for The Pitch—an open-air food court space in Northeast Austin.

“It’s been terrible; there is no one out there,” Hentschel said.

Hentschel said is guaranteeing $20 an hour for servers for the first 90 days—until he determines a pay scale.

“Structurally, we’ve lost a lot of people who used to make a living in the hospitality industry,” Hentschel said. “Either, because of COVID[-19] or everything else, they decided to get a different job.”

Ginn said two challenges employers are facing are a high quit rate and a pool of workers who chose not to return to the economy.

He said many sectors are seeing the cost of items outstrip what consumers can afford and that the effect lead to a recession.

Hockenyos said the coming months will show what the community is willing to pay.

“Will we pay $25 for a cheeseburger?” Hockenyos asked. “I used to laugh about that ... but I’ve seen a cheeseburger on an Austin menu for $23.95. We are there.”