Chatterjee was killed during the Feb. 15, 2002, robbery of his gas station on I-45, according to the Oak Ridge North Police Department. As time went on and leads dried up, the case went cold. However, technological advancements and years of persistence from the city’s police force, including responding officer Lt. Kent Hubbard, eventually led to the arrest of a suspect in late 2019.

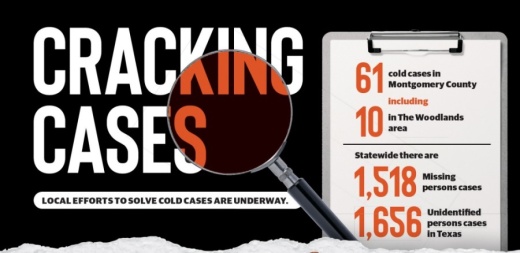

For years, Chatterjee’s slaying was one of the dozens of unsolved cases in Montgomery County. MontgomeryCounty Sheriff’s Office records include 61 cold cases involving missing persons or murders since the late 1970s, including nearly a dozen in The Woodlands area.

On Feb. 2, the sheriff’s office launched a new regional initiative known as Cold Case Warm Up to solicit leads for other unsolved county crimes through a partnership with Clear Channel Outdoor. Billboards throughout the Greater Houston area will display details to solicit tips on local cold cases, beginning with the 1995 murders of Jon and Pansy Stewart in Conroe.

“Someone, somewhere knows something about this case, and we hope that with the creation of all these market impressions throughout the area, someone will come forth with some information that will lead to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators of this particular case,” said Lee Vela, Clear Channel’s vice president of public affairs, at a Feb. 2 press conference announcing the program.

Reopening cold cases

While there is no time limit for assigning cases as cold, Tom Libby, the chief of the Oak Ridge North Police Department, and Shenandoah Police Department Chief Troye Dunlap said agencies can make that designation after determining all avenues of investigation are exhausted. New developments can lead to a case’s reopening, although they said police departments often have limited budgets for cold cases.

Despite roadblocks, some cold cases in Montgomery County have made headway. Montgomery County Forensic Services—which conducts autopsies for the sheriff’s office—partnered with The Woodlands-based forensics lab Othram to solve a 2016 cold case regarding an unidentified deceased man found by kayakers in a reservoir in The Woodlands. The case progressed using DNA technology after traditional forensic evidence analysis failed to generate leads.

“Most people don’t even know how many people are unidentified in this country [or] how many cases remain unsolved,” Othram CEO David Mittelman said.

Since its creation in 2006, Montgomery County’s Cold Case Unit has cracked eight cold cases, two of which involved identifying skeletal remains and six of which led to convictions or the identification of suspected killers, according to Lt. Scott Spencer.

Reopening a cold case requires an extensive review process, said Texas Ranger Robert Bess, who has solved decades-old cases and once worked on a cold case in Montgomery County.

“You have to look at every lab report. You have to watch videos. You have to look at pictures. You have to review autopsies,” he said.

Bess said police who originally worked the case will usually have done everything they could in terms of interviews and other police work, and a key to look for is DNA evidence that has not yet been tested. The county’s cold case unit uses a technology known as Parabon Snapshot-DNA Phenotyping, which takes DNA from an unknown individual to predict ancestry and physical appearance traits, Spencer said.

Familial DNA also proved essential in locating the suspect in Chatterjee’s killing. Oak Ridge North police Lt. Charles Nation said Hubbard was inspired to follow up on DNA matching through Parabond in 2018 and was able to obtain financial support from the county district attorney’s office to fund the new analysis. With those resources, a trail led investigators to a suspect, who officers located and arrested after matching a photo on his LinkedIn.com profile to his place of employment.

While DNA and other technology-based breakthroughs do result in the closure of some cold cases, thousands remain open statewide without such luck or persistent investigation. According to the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, there are 1,518 missing persons cases and 1,656 unidentified persons cases in Texas in early April.

Local collaboration

Libby and Dunlap said neither of their cities have any major cold cases on file. Sheriff’s office records include several unsolved cases in The Woodlands Township—which contracts with law enforcement services with the county—and the wider area around The Woodlands in unincorporated Spring and the southern limits of the city of Conroe.

Libby and Dunlap both said the sheriff’s office and state and national agencies frequently provide assistance that can prove essential in solving local cases when local funding and resources are scarce.

“We try to utilize everybody that we possibly can in these situations,” Dunlap said. “This is a good state as far as support for law enforcement.”

Libby said resolving the city’s homicide case involved working with state, federal and even international agencies. And for cases within the county, the sheriff’s office crime lab and cold case unit are available to local agencies. Spencer said the cold case unit is staffed by two senior detectives.

The oldest known cold case in The Woodlands area is the January 1982 killings of Robert and Janet Genho in their home on Huntsman’s Horn Circle. The pair were shot dead when an unknown suspect or suspects entered their residence, according to police. Alongside the area’s remaining cold cases, sheriff’s office records also show one more recent incident—the 2009 killing of Lisa Lynette Witt Ulloa on Ginger Trace in Spring—that was solved in 2019.

Both city police chiefs said addressing such crimes remains a priority. Libby said Hubbard fostered a relationship with Chatterjee’s family until the case was solved, and the officer still keeps in contact with them even after his 2020 retirement.

“I know when a case is not solved, there’s always a question,” Dunlap said. “You want to close their cases on behalf of the family because you want to solve this to give them a sense of peace that this has been closed, we’ve done everything we can and we’ve come to a resolution to the situation.”

In addition to hard evidence such as DNA, Montgomery County Sheriff Rand Henderson and Vela both noted the potential of the county’s Cold Case Warm Up program for soliciting new information with victims’ names and images displayed across the Greater Houston area, beginning with the Stewarts.

“Through this partnership we hope to develop leads. If anyone in our community has any information on this absolutely senseless murder, we ask that you contact Multi-County Crime Stoppers and relay that information. You may do so anonymously,” Henderson said at the Feb. 2 press conference.

Wading through a backlog

Despite recent efforts from law enforcement and the Texas Legislature, the statewide DNA testing backlog hinders progress on cases, Bess said.

“You’re talking about a lab that’s intaking hundreds, if not thousands, of cases that are being submitted yearly,” he said.

The Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office submits evidence to both state and private labs, Spencer said. Private labs such as Othram can step in if certain technologies or processes are required, Mittelman said.

Texas also faces a backlog of DNA testing kits, including a backlog of 2,138 rape kits, according to End The Backlog, a nationwide nonprofit focused on reforming rape kits. The kits are used to preserve materials from a physical examination after an assault.“You send your DNA to [the state] crime lab—best-case scenario you’re looking at a matter of three, four months ... to get any kind of answer back,” Bess said.

Texas has also enacted various laws intended to improve its handling of rape kits, including House Bill 8 in 2019. Under this legislation, crime labs are required to test kits within 90 days, and agencies are prohibited from destroying rape kits related to a case that has sat unsolved for up to 40 years. According to End the Backlog, the state’s untested rape kit backlog has decreased from 18,955 in 2011 to this year’s 2,138.Dunlap and Libby both said the resources of state law enforcement agencies as well as support at the legislative level can benefit local police work.

“Working those cold cases, it clearly shows the family of the victim that the state of Texas and any other agencies involved outside of Texas are willing, are going to continue with the investigation until its final resolution,” Libby said.